©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Soccer

4

There

are any number of things that will cause popular discontent, civil unrest,

and marauding bands of pitchfork-bearing peasants to start overturning

the king's coaches on the highways. Hunger is one, as is taxation without

representation, but in Naples, getting flim-flammed out of your rightful

place in the football leagues will do the trick quite nicely. If what

happened the other day had happened at any other time of the year, there

might have been real trouble. It is no accident that the news broke

in the middle of August, when the whole city is somewhere else on vacation,

and the few stay-at-homes are sweltering in the worst heat-wave in decades. There

are any number of things that will cause popular discontent, civil unrest,

and marauding bands of pitchfork-bearing peasants to start overturning

the king's coaches on the highways. Hunger is one, as is taxation without

representation, but in Naples, getting flim-flammed out of your rightful

place in the football leagues will do the trick quite nicely. If what

happened the other day had happened at any other time of the year, there

might have been real trouble. It is no accident that the news broke

in the middle of August, when the whole city is somewhere else on vacation,

and the few stay-at-homes are sweltering in the worst heat-wave in decades.

Another

entry explains, roughly, how the Italian football leagues are set

up. At the end of last season, a couple of months ago, Naples pulled

out a couple of victories to finish near the bottom of the "B" football

league. True, that is a long, long way from the glories of the 1980s

and 90s when the team actually won the "A" league championship twice

and was a competitor in most other years, but playing in the "B" league

is a lot better than demotion to the "C" league, which is one step above

the semi-pro and amateur leagues. That would have happened had Naples

not won those few games at the end of last season. So, generally speaking,

Naples football fans were, if not happy, at least relieved.

Now comes

the news that the team is to be relegated to the "C" league for next

reason due not to anything that happened on the playing field, but to

a decision by a judge that the team's "papers" are not in order. In

order to take part in the season every year, teams are required to pay

a fee. That payment is backed by a third-person guarantor. A judge has

determined that, in the case of Naples, the document attesting to the

guarantee is invalid due to an invalid signature.

Such documents

are not mere formalities in Italian sports, and there have been cases

of entire teams being punished for irregularities. The punishment, in

this case, is that Naples is sent down to the "C" league. The open slot

in the "B" league will be filled by Catania, the Sicilian team that

was contending with Naples last season in the league standings to keep

out of last place to avoid being sent down to the "C" league. Naples

made it; Catania didn't. Those results have now been reversed by the

recent decision. Naples has a very short time—a few days—to

appeal the decision, because the playing season is about to start. The

crux of the appeal will be, one, that there was nothing wrong with the

guarantor's papers and, two, that the judge who ruled against Naples

is from Catania.

The judge

in question anticipated some of that in this morning's paper. "It is

irrelevant that I am from Catania," he says. "I'm not a sports fan.

The last time I set foot in a stadium was in 1974. I'm a judge. I apply

the law."

Lepanto,

Battle of; Santa Maria della Vittoria

Many cities have squares, streets and monuments named

for "victory". In many cases, the victory—the particular

battle or war—is left unnamed since at their dedication

"everyone knows". It's simply "Victory Square". How could anyone NOT

know? Frailty, thy name is memory; I have checked with a number of Neapolitans

to see what they know about Piazza Vittoria (Victory Square)

at the east end of the Villa Comunale. The most common answer is, "Oh,

that's where the number 28 bus [alternately the number 1 street-car]

turns around". Occasionally, you get a vague "named for some war or

other" answer. And on rare occasion, someone knows: The Battle of Lepanto.

Technically speaking, the square is named for the Church in the square:

Santa Maria della Vittoria, which was, indeed, named for the

battle—but that's close enough. Many cities have squares, streets and monuments named

for "victory". In many cases, the victory—the particular

battle or war—is left unnamed since at their dedication

"everyone knows". It's simply "Victory Square". How could anyone NOT

know? Frailty, thy name is memory; I have checked with a number of Neapolitans

to see what they know about Piazza Vittoria (Victory Square)

at the east end of the Villa Comunale. The most common answer is, "Oh,

that's where the number 28 bus [alternately the number 1 street-car]

turns around". Occasionally, you get a vague "named for some war or

other" answer. And on rare occasion, someone knows: The Battle of Lepanto.

Technically speaking, the square is named for the Church in the square:

Santa Maria della Vittoria, which was, indeed, named for the

battle—but that's close enough.

The small

church and an adjacent monastery were built in 1572, the year following

the epic sea battle between the Turks and the Holy League, a combined

European naval force promoted by Pope Pius V. It has been called the

"last crusade," a battle not just between rival nations, but between

rival civilizations—in this case, Islam and Christianity. It was,

in every respect, as important to the survival of the West as the Battle

of Marathon, and if the Holy League had not won, nothing could have

prevented the Turks from advancing into Europe, from taking Rome, itself.

Battle

was joined on the October 7, 1571. It had been preceded by the Turkish

conquest of Cyprus in 1570, and, of course, in the previous century

by the Turkish conquest of Constantinople—the fall of the Byzantine

Empire. There was no doubt in the mind of the Pope which way the wind

was blowing. He got Venice, Genoa, Spain (and thus, Naples and Sicily—part

of the Spanish Empire at the time) to assemble a fleet of over 200 ships

to meet the slightly larger Turkish fleet south of Cape Scropha in western

Greece, near Lepanto ("Epakto" in Greek). Though outnumbered and less

manoeuvrable, the Western fleet was more modern, relying on cannon,

as opposed to the Turks, who still relied on bows and arrows and getting

in close enough to board. The losses were staggering. When the single

day was done, 85% of the Turkish fleet had been sunk and 20,000 Turks

killed; 8,000 soldiers in the Western fleet perished. The Holy League

then disbanded, Europe went back to parochial bickering, and all was

right with the world.

The Church

of Maria della Vittoria was then rededicated in the early 1600s by the

daughter of John of Austria, the commander of the Western fleet. The

monastery part of the building was vacated in the early 1800s and since

that time has been used for private residences. The square, itself,

was expanded in the 1890s as part of the Risanamento,

the great urban renewal of Naples. That construction enlarged Piazza

Vittoria up to the new street, via Caracciolo, at water's edge, and

provided a quaint, hanky-sized harbor and bathing beach (photo, above).

The beach has no real name other than the hybrid "Mappatella

Beach" (using the English term). A mappatella is a small bundle

made by drawing up the corners of a rectangular piece of cloth (which

is how you packed to go to the beach in the days before the ubiquitous

backpack or plastic sack). The small harbor has a few fishing

boats in it and is marked by a monument to those who have died at sea.

The monument is a single Roman column with the top missing (photo insert,

above) and thus is called, simply, la colonna spezzata—the

"broken column". It was found on Via Anticaglia, one of the old

main roads of Roman Naples.

Bourbons

(2)

(part 1 is here.)

| As

they say, a man who needs no introduction. This is a detail from

one of four versions of Napoleon Crossing the Alps by Jacques-Louis

David. |

Southern

Italy had gone its own way for a thousand years, since Charlemagne's

failure to reunite the entire peninsula. It is, perhaps, a strange coincidence

that another conqueror, also doomed to fail, should set in motion the

machinery that would lead to the south being woven back into the common

fabric of Italy. Southern

Italy had gone its own way for a thousand years, since Charlemagne's

failure to reunite the entire peninsula. It is, perhaps, a strange coincidence

that another conqueror, also doomed to fail, should set in motion the

machinery that would lead to the south being woven back into the common

fabric of Italy.

Beginning

in 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte swept across Europe in a virtuoso display

of military genius, political ambition and radical social change. In

the space of four years he made himself King of France, then King of

"Italy" (a satrapy he carved out of northern Italy), and then Emperor!

In so doing he forced the official emperor to abdicate, ending the Holy

Roman Empire forged by Charlemagne. By shaping much of Germany into

the so-called "Confederation of the Rhine" in 1806 and imposing the

legal system known as the Napoleonic Code, he put an official end to

feudalism in central Europe. Militarily, he took on the rest of Europe

and at least on land was victorious at virtually every turn (his defeats

at the hands of the British at sea were crucial, however). His goal

to create a single Empire from the British Isles to the Mediterranean,

from the Atlantic to the Ural mountains failed. But it was close.

Napoleon

was impatient with the Kingdom of Naples. In a blunt letter to Queen

Maria Carolina, he told her:

"What

must I think of the kingdom of Naples … when I see at the head

of its administration a man who is alien to the country… [referring

to Acton, the prime minister]…

I have therefore decided… to consider Naples as a country ruled

by an English minister. I am loathe to meddle in the internal affairs

of other states… yet… "

With that,

and further motivated by his distrust of Neapolitan professions of neutrality

regarding French disputes with the Austrians and British, Bonaparte

sent troops into the Kingdom of Naples, forcing the royal family to

flee south again, just as during the brief period of the Parthenopean

Republic a few years earlier and again hunker down on Sicily as a separate

little island kingdom. Napoleon sent his brother, Joseph, to be

King of Naples, then juggled Joseph over to the throne of Spain and

replaced him in Naples with their brother-in-law, the dashing cavalry

officer, Joachim ('Gioacchino' in Italian) Murat.

Murat was

the King of Naples from 1808 to 1815. The Napoleonic Code transformed

southern Italy. It dismantled the privileges of the churches and the

barons, reordered the courts and set up schools for the education

of the general population. Not only in the south, but all over the Italian

peninsula, this autocratic imposition of the ideals of the French Revolution

would outlast Napoleon, himself, and would help shape eventual national

aspirations for a single nation stretching from from Sicily to the Alps.

Murat even saw himself as the future King of all of Italy and, thus,

he encouraged secret societies such as the Carbonari,

hotbeds of pan-Italian nationalism. Ultimately, with the defeat and

exile of Napoleon, Murat's fortunes crumbled. His own attempts to resist

the restoration of the Bourbons dictated by the Congress of Vienna in

1815 failed when his southern army was defeated by the Austrians. He

fled to Corsica and made one last futile attempt —truly à

la Bonaparte!— to return from exile and raise an army to retake

his kingdom. He was taken prisoner and shot.

Portrait

of Ferdinand (Royal Palace)

After

the restoration, the former Ferdinand IV returned as Ferdinand I of

the United Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Times, however, had changed.

First of all, his wife, who had practically run the kingdom during the

entire course of their marriage, had died. Second, the growing middle

class of entrepreneurs, intellectuals, military professionals, and new

property owners had set their sights on representative government, a

constitution. And third, all over Italy were stirring sentiments echoed

by Manzoni's famous line: "We shall not be free until we are one." (Ironically,

he got that phrase from Cuoco, a Neapolitan

philosopher). After

the restoration, the former Ferdinand IV returned as Ferdinand I of

the United Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Times, however, had changed.

First of all, his wife, who had practically run the kingdom during the

entire course of their marriage, had died. Second, the growing middle

class of entrepreneurs, intellectuals, military professionals, and new

property owners had set their sights on representative government, a

constitution. And third, all over Italy were stirring sentiments echoed

by Manzoni's famous line: "We shall not be free until we are one." (Ironically,

he got that phrase from Cuoco, a Neapolitan

philosopher).

But Naples

was suffering from—to use Croce's phrase—the "stamp of illiteracy',

brought about by the flight of and persecution of intellectuals, liberals

and other supporters of Murat and of the earlier Parthenopean Republic.

Now, the old lazzarone, the king who had always felt most at

home among the peasantry, no longer even trusted his own subjects to

support him. He imported companies of Swiss mercenaries to augment his army.

Ferdinand

was forced to relinquish absolute rule and grant a constitution to Naples

in 1820 as a result of a carbonari-led revolution. The last thing

he did in his life, however, was to reaffirm his spiritual allegiance

to another century by getting Austrian help to suppress the constitutional

government and carry out brutal reprisals against the leaders. He died

in 1825 after one of the longest reigns (excluding Napoleonic interruptions)

in European history, having ascended the throne in 1759. He had outlived

his wife, two capable prime ministers (Tanucci and Acton) and, quite

clearly, his time. His son, Francis I, succeeded him for a brief period

and then, in 1830, the grandson, Ferdinand II, came to the throne.

The

inauguration in 1839 of the first railway in Italy, from Naples to Portici.

The

last thirty years of the existence of the Kingdom of Naples are marked

by great strides in science, technology and industry. The first railways

and iron-suspension bridges in Italy were in the south, as was the first

overland electric telegraph cable. Also, the fleet of the Kingdom of

Two Sicilies was the largest merchant fleet in the Mediterranean.

By 1839, the main streets of Naples were gas-lit. Ferdinand II even built the cliff-top road along the

Sorrentine peninsula. To some, such accomplishments define a sort of

Golden Age similar to that under Charles III a century earlier. Much

Bourbon achievement at mid-nineteenth century, however, was possible

only because Murat had laid the groundwork decades earlier by reforming

the university and founding various scientific academies. The

last thirty years of the existence of the Kingdom of Naples are marked

by great strides in science, technology and industry. The first railways

and iron-suspension bridges in Italy were in the south, as was the first

overland electric telegraph cable. Also, the fleet of the Kingdom of

Two Sicilies was the largest merchant fleet in the Mediterranean.

By 1839, the main streets of Naples were gas-lit. Ferdinand II even built the cliff-top road along the

Sorrentine peninsula. To some, such accomplishments define a sort of

Golden Age similar to that under Charles III a century earlier. Much

Bourbon achievement at mid-nineteenth century, however, was possible

only because Murat had laid the groundwork decades earlier by reforming

the university and founding various scientific academies.

More relevant

than industry to Naples' real future, that is, its participation —or

lack, thereof— in the struggle for Italian unity, was Ferdinand's

inability to read the handwriting on the wall. Two of his comments

bear repeating: "I don't know what is meant by an independent Italy

—I only understand an independent Naples," and "My kingdom starts

at seawater and ends at Holy Water," (referring to Sicily in the south

and the Papal States in the north). Clearly, this mentality was at odds

with nationalist sentiments of groups such as Mazzini's Young Italy,

agitating all over the north to unify the peninsula.

General

revolution in the name of constitutional government swept Europe

in 1848. In Naples, the king, like his grandfather before him,

was forced to grant a constitution. Neapolitan troops actually went

north to join the fight against the Austrians in what would become known

as the First War of Italian Unification, but they were recalled to the

south when their King, again like his grandfather, staged a counterrevolution

and revoked the constitution. At this point, thousands of intellectuals

and liberals fled north to join the struggle for "Italy." It was now

the only game in town, and they would be part of it—with their

King, if possible, but without him, if need be.

Ferdinand,

thus, denied the South the opportunity of being part of the Risorgimento,

the movement for a single Italy. He became ever more absolutist and

isolated. He died in May, 1859 and was succeeded by his son Francis

II, destined to be the last king of Naples. Although Francis tried to

stave off the inevitable by giving in to liberal demands to restore

the constitution, it was much too late for such half-measures. The Kingdom

of Naples had come full circle: founded by the Norman invasion of Sicily

eight hundred years earlier, it was about to end by another invasion

of the same island, this one led by Giuseppe Garibaldi.

[continued

at Bourbons (3)]

Mercadante

Theater

When the Jesuits were expelled from the Kingdom of Naples

in the 1770s, a fund was set up to handle the new wealth that had accrued

to the Kingdom from the confiscated property. One decision was to build

a new theater, appropriately called the Teatro Fondo (after the

"fund" that had underwritten the construction). It was inaugurated in

1779 and was intended to be more a vehicle for lighter theater, such

as the Comic Opera, and not to be in direct competition with nearby

San Carlo, generally given to more serious works. Unlike smaller, private

theaters in Naples at the time, the Teatro Fondo was sponsored by the

state; it was a "royal theater" like San Carlo and was prestigious. When the Jesuits were expelled from the Kingdom of Naples

in the 1770s, a fund was set up to handle the new wealth that had accrued

to the Kingdom from the confiscated property. One decision was to build

a new theater, appropriately called the Teatro Fondo (after the

"fund" that had underwritten the construction). It was inaugurated in

1779 and was intended to be more a vehicle for lighter theater, such

as the Comic Opera, and not to be in direct competition with nearby

San Carlo, generally given to more serious works. Unlike smaller, private

theaters in Naples at the time, the Teatro Fondo was sponsored by the

state; it was a "royal theater" like San Carlo and was prestigious.

During

the brief duration of the Neapolitan Republic in 1799, the name was

changed to Il Teatro Patriottico, and monarchist fluff such as

Comic Opera was abolished in favor of the

more politically educational fare of republican theater. Between 1809

and 1829, the theater was managed by Domenico Barbaja, who was also

the director of San Carlo. During that period, many works that one would

normally associate with San Carlo—the works of Mozart, Rossini, Donizetti,

and Bellini, for example—were

commonly performed at the Teatro Fondo.

The name

of the theater was changed to the Mercadante Theater in 1870 to honor

Saverio Mercadante, a prominent Neapolitan composer and director of

the Naples Music Conservatory, who had

just passed away. Although obscure today, Mercadante enjoyed a considerable

reputation during his lifetime and was mentioned in the same breath

as Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini and even Verdi as one of the great Italian

composers of the 19th century. His entire life was bound up with Naples;

he entered the Naples Conservatory in 1808, became the composer–in–residence

at San Carlo in 1823, the director of the conservatory in 1840, and

from 1845-55 the director of San Carlo.

For reasons

having to do with his support of the Carbonarist Revolution in Naples in 1820-1, Mercadante

left Naples for a few years and worked in northern Italy, Austria and

Spain. Reconciled with the Bourbon monarchy in Naples, he returned to

continue his career as composer and musical impresario. He is best remembered,

historically, as one who tried to revitalize Italian instrumental music

(as opposed to opera) and one who introduced Neapolitan audiences to

the music of contemorary German composers. Mercadante was held in such

high esteem that when the Kingdom of Naples collapsed before the forces

of Garibaldi, he was kept on as director of the Conservatory, where

he turned out an orchestral hymn to Garibaldi—no doubt with the

same professionalism as a year earlier when he had composed the coronation

music for Francis II, the last King of Naples.

In the

latter part of the 19th century, the Mercadante Theater gradually left

music to San Carlo and concentrated on plays and, later, vaudeville.

The theater was damaged in WW2. Now, after decades of difficult false

starts, the Mercadante has been restored and is once again in a position

to host significant contributions to the cultural life of the city.

As one sees the theater today, the façade is the redone version

from 1893, the decade of the great urban renewal

of that part of the city. Today, over 100 years later, the Mercadante

is flanked by bigger and, frankly, ugly buildings such that it now stands

out like a gem.

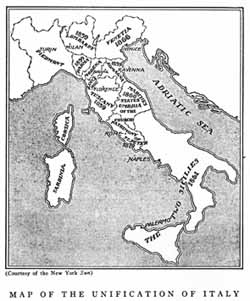

Garibaldi

(U.S. reaction to) (1)

I'm

reading another one of Howard Marraro's interesting books (also see

here), this one entitled American Opinion on the Unification

of Italy, 1846 –61, first published in 1932. He stitches together

and comments upon newspaper items, magazine articles, pamphlets, and

speeches and messages of American public figures from those years to

show what the public in the United States felt, generally, about the

broad issue of Italian unity and, specifically, how it reacted to the

conquest of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies by Garibaldi. I'm

reading another one of Howard Marraro's interesting books (also see

here), this one entitled American Opinion on the Unification

of Italy, 1846 –61, first published in 1932. He stitches together

and comments upon newspaper items, magazine articles, pamphlets, and

speeches and messages of American public figures from those years to

show what the public in the United States felt, generally, about the

broad issue of Italian unity and, specifically, how it reacted to the

conquest of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies by Garibaldi.

Public

opinion in the United States was overwhelmingly behind the Risorgimento,

the drive to unite Italy. There was some dissent among Roman Catholics

and in the Catholic press, which knew that the unity of Italy would

mean the end of the1000-year-old Vatican States, the broad buffer zone

between northern and southern Italy, and, thus, the end of the "temporal

power of the Pope". Other than that, opinion was enthusiastically behind

Garibaldi and his daring campaign to free the long-suffering peasantry

of the Kingdom of Naples from the yoke of centuries of oppression —

(yes, just such rhetoric). It was common to see and hear Garibaldi referred

to as the "Washington of Italy," high praise, indeed, from Americans.

They sent more than their good wishes, too. Americans sent money and

even material help; a number of US citizens residing in Italy at the

time actually fought with Garibaldi, and some American merchant captains

put their vessels at Garibaldi's disposal to cross the straits of Messina

to begin his march towards Naples in 1860.

Strangely

related to that is an item I found about the recent addition to the

library of the University of South Carolina of the Anthony P. Campanella

Collection, a formidable array of material about Garibaldi. The text

describing the collection and donation contains this paragraph:

| There

can be no doubt that the March, whose progress was eagerly followed

in a United States ideologically opposed to European dynastic

"tyranny," was viewed in this country as a powerful vindication

of the right of the individual to political self-determination.

It also encouraged Southern leaders in their move towards secession

at precisely the time when accounts of Garibaldi's exploits appeared

in the American press. Nor is it coincidental that in 1876 Wade

Hampton's followers, in their resistance to the continued presence

of Federal troops in South Carolina, appropriated the name of

Garibaldi's followers—Red Shirts—for themselves. |

[The

entire item is on the internet at http://www.sc.edu/library/spcoll/hist/garib/garib.php

]

I find

at least some of that strange. I am prepared to take the word of the

gentleman who wrote those lines that there might have been something

inspiring in the heroics of the anti-tyrant, Garibaldi, something that

appealed to those in the south who felt they, too, were suffering under

tyranny—the tyranny of federalism. (Indeed, a year later, those

southerners commonly referred to their cause as The Second American

Revolution). (At the risk of being really wrong, I wonder, too,

if there is not parochialism in that paragraph. He is writing on behalf

of the University of South Carolina —South Carolina, the birthplace

of the Confederacy.)

Also, I

strain to believe that any southerners after the Civil War would

have appropriated Garibaldi's name or symbols to their lost cause. Surely,

they knew that Lincoln, in 1861, had offered Garibaldi the position

of a general in the field for the Union armies, and that the only reasons

Garibaldi turned Lincoln down were (1) that Lincoln wouldn't make him

commander-in-chief (Abe already had that job) and (2) that Lincoln wouldn't

let him free slaves wherever he found them during his military campaigns.

(Invading plantations and liberating slaves in South America had been

one of Garibaldi's favorite things to do during his younger days, when

he was abroad and training for the big fight).

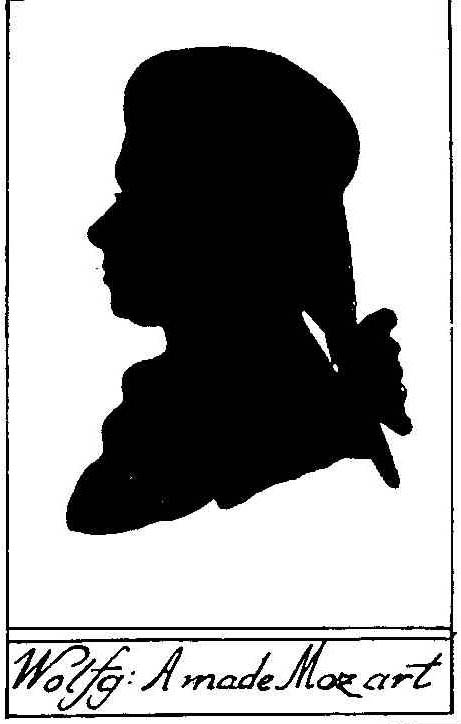

Comic

opera, Neapolitan (and Mozart)

In a letter

to his sister in May of 1770, Mozart wrote from Naples that…"An

opera composed by Jomelli begins on the 30th. We have seen the king

and queen at Mass in the royal chapel at Portici, and we have seen

Vesuvius, too… Madame de Amicis is singing at the opera. We

have been to visit her. Caffaro is the composer of the second opera,

Ciccio di Majo of the third…". In a letter

to his sister in May of 1770, Mozart wrote from Naples that…"An

opera composed by Jomelli begins on the 30th. We have seen the king

and queen at Mass in the royal chapel at Portici, and we have seen

Vesuvius, too… Madame de Amicis is singing at the opera. We

have been to visit her. Caffaro is the composer of the second opera,

Ciccio di Majo of the third…".

A

few weeks later he wrote, again to his sister, that "… the opera

here is by Jomelli; it is beautiful, but too discreet and old-fashioned

for the theater. Madame de Amicis sings incomparably… The theater

is handsome. The king …always stands on a stool at the opera

to appear a little taller than the queen. The queen is beautiful and

courteous…"

Mozart

was only 15 when he wrote those letters; he was in Naples with his father

as part of a tour of Italy to further his musical education. Naples

was of extreme interest to any composer of that period because it was

the home of the fine conservatories as well as the most beautiful theater

(San Carlo) in Europe. Also, it was the birthplace of the most popular

form of musical entertainment of the eighteenth century, the Comic Opera.

If your

view of opera is that is necessarily entails death by consumption, jumping

from high places, getting stabbed by your lover or, in the case of much

of Wagner, being pecked to death by mythologically huge swans, you will

be happy to know that such has not always been the case. Those of you

with funny bones will appreciate that the record for the longest encore

ever played at the end of an opera was a repetition of the entire work!

It was in 1792 and the work was a comic opera entitled The Clandestine

Marriage by the Neapolitan composer Domenico Cimarosa. It was premiered

at the Burgtheater in Vienna, and as noted, the Emperor liked it so

much that he ordered dinner for everyone before having the company do

the whole thing again.

By the

early 1700s, opera, the musical theater, in Europe had reached somewhat

of an impasse. It was musically confusing, unable to decide on priorities

between plot and music, often sacrificing everything to mere vocal virtuosity.

And it was often dreary, still based, as it was, on the same Greek mythological

themes that had given rise to the original melodramas of Monteverdi

a century earlier. The balance between the importance of music versus

the importance of text had shifted from text (where it been in the late

1500s) to music; that is, after a century of the powerful musical influence

of Monteverdi, there was no doubt by 1700 what was more important—music.

One thing

had to happen to keep melodrama from dying of all melo– and no

drama: restore meaningful text; give people stories they could enjoy.

One way to do this was to restore the literary value of the typical

tales of classical mythology. This happened in the person of Metastasio, the greatest Italian librettist

of the 18th century and one of the finest Italian poets of that century.

His Didone Abbandonata from 1724 marks the rebirth of real poetry

in the Italian libretto.

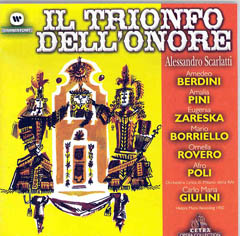

Another

way was to turn to more modern stories and set them to music. Enter

the Neapolitans, who began livening up evenings at the opera by inserting

light–hearted little interludes—called "intermezzos"—

between the acts of the more serious stuff. They broke up an evening

of Achilles or Ajax or Opheus with a few minutes of fluffy domestic

farce set to delightfully singable melodies. Alessandro

Scarlatti's Il trionfo dell'onore, given 18 times at the

Teatro dei Fiorentini in 1718, is chronologically the first comic

hit of this newer light-hearted fare.

From there,

an entire school of composers (see composers, other) dedicated themselves to

such music. In 1733 Neapolitan composer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi's

La serva padrona (The Maid Mistress) was produced. In 1749, some

years after the composer's death, the opera swept Italy and France,

literally revolutionizing the musical theater. (In 1741, the Comic Opera

as comic intermezzo had ended when King Charles III decided it was inappropriate

to have such folderol break up Greek tragedy. Put that stuff in a separate

theater, he said. They did, and the independent Comic Opera was born.)

In 1760, Niccolò Piccinni wrote the music to La Cecchina

on a text by the great Venetian playwright, Goldoni. That text was based

on a very popular English novel, Pamela or Virtue Rewarded, from

1740, by Samuel Richardson. Many years later, Verdi, himself, called

La Cecchina, the "first true comic opera"—that is to say,

it had everything: it was no longer simply an intermezzo; it had a real

story that people liked; it had dramatic variety; and, musically, it

had strong melodies and even strong supporting orchestral parts including

a strong, almost "stand-alone" overture (i.e. you could enjoy it as

an independent orchestral piece).

From then

until the end of the century, many of Europe's best-loved composers

were Neapolitans working within the framework of the comic opera: Pergolesi,

Paisiello, Cimarosa,

among others. Mozart had come to Naples to listen to the music of these

composers and to learn from them. He spent a short but thoroughly

enjoyable time in Naples, taking in the sights and, of course, the sounds.

He attended the opera, and he gave piano recitals of his own, during

one of which, so the story goes, the young genius was required by the

public to take off a ring he was wearing just to show that it wasn't

magic and that he could still play without it!

Like every

other musical form that Mozart touched, he perfected the comic opera,

too. His own works have so overshadowed the music of his Neapolitan

contemporaries that of the literally hundreds of comic operas produced

in Naples in the latter part of the 18th century, perhaps the only two

still in the standard repertoire of opera companies elsewhere are two

mentioned above: The Clandestine Marriage and The Servant

Mistress.

The contemporary

Neapolitan composer and musicologist Roberto de Simone has dedicated much of his activity

to reviving a number of these 'lost' Neapolitan comic operas. They are

generally well-received, but music that has to be revived will probably

never again find a permanent place in the musical consciousness of the

public. In a certain sense, we have become addicted to the passions

of Romanticism. We will never be able to listen to this delightful music

of the 18th century without first filtering it though our knowledge

of 19th and 20th century music. We'll never appreciate it the way Mozart

did when he was here. He heard it fresh, and he liked it. It was something

he could work with.

Sebeto

river

I came across a passage that read: "Perhaps only the

elderly recall the legends of love that blossomed on the shores of the

Sebeto." I asked an elderly friend (95 years old) here in Naples what

he knew about (1) legends of love and (2) the Sebeto river, which

used to flow from its source near Nola and down through the eastern

part of Naples, well outside the ancient walls, and into the sea. He

said: "That's the same line I heard when I was young. 'Only the elderly

recall the Sebeto.' I don't know a thing about it." I came across a passage that read: "Perhaps only the

elderly recall the legends of love that blossomed on the shores of the

Sebeto." I asked an elderly friend (95 years old) here in Naples what

he knew about (1) legends of love and (2) the Sebeto river, which

used to flow from its source near Nola and down through the eastern

part of Naples, well outside the ancient walls, and into the sea. He

said: "That's the same line I heard when I was young. 'Only the elderly

recall the Sebeto.' I don't know a thing about it."

References,

both classical and modern, to the Sebeto River in Naples are plentiful.

There is a Greek coin minted in Naples in the fourth century B.C. bearing

the head of the young river-god with his name, "Sepeithos". Virgil mentions

the river, as do Italian medieval writers such as Boccaccio. The Neapolitan,

Jacopo Sannazzaro, called the river "my Neapolitan Tiber". Pontano spoke

of the placid waters of the Sebeto, and Veronica Gambara (1485-1550),

one of Italy's first women poets of distinction, wrote, "Là

dove or d'erbe adorna ambe le sponde/il bel Sebeto..." ("There where

green adorns the banks of the beautiful Sebeto"). Also, near the Mergellina

harbor, there is a large, marvellous fountain (photo) dedicated to the

Sebeto. It was built by Cosimo Fanzago in 1635.

More recently,

there are hydrologic reports on the "Sebeto depression," a Sebeto literary

prize, Sebeto internet addresses, at least one Sebeto street in Naples,

a theater, a 1989 book called The Mysterious Sebeto and plans

to build a green urban park along what used to be the banks of what

used to be the river. Apparently the river still exists, at least to

some extent, as a subterranean stream since a report on the contruction

of new stations for the Circumvesuviana train-line in the extreme eastern

end of the city mentioned the problem of underground water.

The last

elderly person to recall the green banks of the Sebeto must have lived

in the mid-19th century and recalled a time before the Bourbons went on a swamp-draining binge late in the

previous century. They succeeded in drying up the marsh area near what

is now the Maddalena Bridge in the industrial section of the city. Apparently

they dried up the river as well.

Santa

Maria Francesca

Everyone,

of course, knows that the patron saint of Naples is San Gennaro (St. Januarius), but of the six people

I've just spoken to—and I include myself in that group—not

one of us knew that Naples has a co-patron-saint. Maybe the reason for

our ignorance is that we all live up on the hill above the "real" city,

a section of Naples that is, if not well-off snooty, at least severely

gentrified. But if you get down into the Spanish Quarter, off of via Toledo, everyone knows

about Santa Maria Francesca, the only Neapolitan woman ever to be elevated

to sainthood by the Roman Catholic church. Everyone,

of course, knows that the patron saint of Naples is San Gennaro (St. Januarius), but of the six people

I've just spoken to—and I include myself in that group—not

one of us knew that Naples has a co-patron-saint. Maybe the reason for

our ignorance is that we all live up on the hill above the "real" city,

a section of Naples that is, if not well-off snooty, at least severely

gentrified. But if you get down into the Spanish Quarter, off of via Toledo, everyone knows

about Santa Maria Francesca, the only Neapolitan woman ever to be elevated

to sainthood by the Roman Catholic church.

She was

born Anna Maria Rosa Nicoletta Gallo in 1715 in Naples and died there

in 1791. She entered a religious order at the age of 16 to escape a

particularly harsh and abusive family environment. She took the religious

name of Santa Maria Francesca delle cinque piaghe (Saint Mary

Francis of the Five Wounds of Jesus). She spent the last 38 years of

her life as a "home saint," as it is idiomatically called in Italian.

That is something like a "worker priest"; that is, she did not live

a reclusive life in a convent; she lived in a private home and spent

all her time working with and for the poor in the area. She was beatified

by Gregory XVI in 1843, and canonized by Pius IX in 1867. Since the

beatification, there has been a chapel in the left nave of the Cathedral

of Naples dedicated to her. In 1856, Ferdinand II of Naples acquired

the house she had lived and died in and made it into a small church

named for the saint, the church of Santa Maria Francesca delle cinque

piaghe. It is on a street called vico tre re a Toledo in

the Spanish Quarter (photo).

That small

church made the news today because a small statue—not much more

than a doll, really—of the Infant Jesus wearing a silk garment

with threaded gold hand-sewn by St. Mary Francis, herself, was stolen

a few days ago. The aged nun in charge of caring for the object, 90-year-old

Sister Aurora, was apparently set-up: one thief distracted her with

a question, and the other thief popped the cover on the small display

case and made off with the statue. Sister Aurora has refused to eat

since then, and a second member of the order, Sister Veronica says,

"I hope this is not sinful of me, but I hope they [the thieves] find

no peace". The police and a squad from the Superintendancy of Culture

are on the case, as are members of the church congregation. It is a

rough section of town, and if this story has a happy ending, small bands

of "angels with dirty faces" will hunt down the ne'er-do-wells and give

them a heavy dose of "no peace" before returning the Baby Jesus to the

devotees of St. Mary Francis.

Salerno,

Duchy of

Sichelgaita—Warrior

Princess, and then some.

What

bizarre, zigzag chain of events—even for the Middle Ages—led

to the unlikely sight, in May, 1076, of a fair young princess, clad

in shining armor and astride her steed, riding next to her husband,

Robert of Hauteville (known as Robert "Guiscard"—the Wise), right

up to the walls of her own native city of Salerno, ruled by her own

brother, and demanding its surrender? What

bizarre, zigzag chain of events—even for the Middle Ages—led

to the unlikely sight, in May, 1076, of a fair young princess, clad

in shining armor and astride her steed, riding next to her husband,

Robert of Hauteville (known as Robert "Guiscard"—the Wise), right

up to the walls of her own native city of Salerno, ruled by her own

brother, and demanding its surrender?

Thereby

hangs quite a tale, and you can keep it straight only if you know the

cast of characters who were competing for the upper hand in Europe—and

particularly in the case of our story, southern Italy—between

the years 1000 and 1100. There are at least 5 major players. In no particular

order, they are:

1. The

Holy Roman Empire

2. The

Church of Rome

3. The

Byzantine Empire

4. The

Normans

5. The

residual Lombard duchies in southern Italy, in particular, the Duchy

of Salerno.

(1) The Holy Roman Empire was formally proclaimed in 800 with

Charlemagne as emperor. It was essentially what replaced the loose hodge-podge

of "barbarian" states occupying the former western Roman Empire. It

was the first great northern power base in Europe and was the forerunner

of individual European nation states such as France and Germany. The

Holy Roman Empire lasted until 1806 when Francis II, faced with Napoleon's

proclamation of a new empire, abdicated.

(2) By

the Church of Rome is meant here the territory of the Papal States,

taking up much of central Italy and coming into being as result of the

so-called "Donation of Pepin" in the mid-700's. That gift of land turned

the Church into a secular power with enough might to field armies and

crown emperors.

At this

point, note the "Holy" in Holy Roman Empire. The Empire and the Church

of Rome started out in a symbiotic relationship, each depending on the

other for validation or military support, depending on the times. It

is significant that Charlemagne was crowned emperor by the Pope, himself.

That event marked the end of secular Europe (pre-Europe, really) and

the beginning of large-scale involvement by the Church in continental

politics, involvement that would last until the Empire, itself, was

dismantled by Napoleon a thousand years later. The infamous Church vs

State enmity (typified by the 'Guelph' and 'Ghibelline' factions of

the 14th century) can be traced to the great reform movement within

the Church in the mid-1000s, spearheaded by the monk Hildebrand,

later to become Pope Gregory VII. His call for what amounted to a theocracy

and a totally subservient Empire alienated the "princes of the earth".

(3) The

Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, had its

beginnings under Constantine the Great, the founder of the city in 330

that would bear his name until the fall of that city to the Turks in

1452. After the fall of Rome in 476 and even through and beyond the

Lombard rule in Italy (568-774), Byzantine forces actively contested

much of Italy and did not totally withdraw until well into the 1100s.

(4) Few

peoples have been as explosive and expansive as the Normans.

They started as Danish Vikings, the Norsemen who invaded Britain in

the mid-800s. In that same period, they marauded almost everywhere,

sacking cities from Canturbury to Paris to Constantinople; yet they

also founded lasting Russian dynasties in Kiev and Novgorod.Then, in

911, they took the area of northern France that would be named for them—Normandy.

In the late 900s and early 1000s the Vikings were sailing to Iceland

and North America; by 1015 their cousins from Normandy would be probing

southern Italy. They would then retake Sicily from the Arabs in the

mid-1000s—a very difficult struggle. They would invade and subdue

Britain in 1066. All in all, they were a swashbuckling race of

people -- and they were ambitious. Just how ambitious would not be clear

until the greatest of them, the Robert Guiscard mentioned in the first

paragraph, above, revealed his plans not just to rule southern Italy,

but to take over the Byzantine Empire and reunite the Eastern and Western

churches and, then, possibly, to move even further east as had Alexander

the Great.

(5) The

Lombards really have two histories in Italy. The first is as

the great Lombard kingdom of Italy from 568-774. They were the last

"barbarians" to invade the Italian peninsula after the fall of the western

Roman Empire and ruled much of the peninsula as a loose confederation,

contesting much of the territory much of the time with the Byzantine

Empire. That grand Lombard kingdom came to an end when Charlemagne invaded

Italy and defeated the Lombards in the north of Italy in 774.

The other

Lombard history concerns our story. Charlemagne, though calling himself

"King of the Lombards" (and annexing the north of Italy to the Holy

Roman Empire) left undefeated and largely intact the vast area of southern

Italy with its separate residual Lombard holdings, most important of

which was the Duchy of Benevento. That duchy, itself, underwent a civil

war in 839, giving birth to an independent Duchy of Salerno.

In the

course of the next two centuries Salerno developed into one of the cultural

centers of Europe. It was primarily famous for its medical school, the

first of its kind in Europe. It was here that disease became something

to be diagnosed, treated and, potentially, cured, thus adopting what

one day would be called a "scientific" approach and abandoning the Christian

monastic treatments of prayer and mortification of the flesh. Herbal

pharmacology was studied, as was anatomy and surgery --even early attempts

at anaesthesia. The school also hosted a group called the "Ladies of

Salerno", foremost of whom was Trotula, who taught about and wrote important

early works on the medical problems of women. Women studied there, as

well, and one such student was the not-yet "warrior princess", Sichelgaita.

The medical school attracted scholars from throughout Europe.

Also, given

the pre-Crusades anything-goes atmosphere of the independent ports of

commerce such as Naples, Salerno, Amalfi and Gaeta, there was surely

exchange of information --as well as goods-- between them and the Muslim

world. Wary of the post hoc fallacy of confusing sequence with

cause and effect, we may nevertheless note that there were earlier Muslim

models of modern medical schools and that the school in Salerno may

have benefited from such exchange.

So,

with that...

| The

Duchy of Salerno in the 11th century, before the Norman consolidation

of southern Italy. (From Muir's Historical Atlas, 1911). |

Sichelgaita

was born in 1035 into the ruling family of the Duchy of Salerno. She

was the daughter of Gaimar V, who was murdered in a palace coup. Her

brother, Gisulf, retook the Duchy, and she retook her place as the most

privileged woman in the Duchy. She spent much of her time studying medicine

and—an unlikely combination, perhaps—pursuing the "manly"

arts of horseback-riding and swordplay.

Her native

Lombard Duchy of Salerno was by 1050 already in trouble, at least potentially.

It had held the ever-encroaching Byzantine forces at bay, but the Normans

would be more difficult. The Normans had come on the southern

Italian scene in the early 1000s. Depending on the source you choose

to believe, they originally were either pilgrims who liked what

they saw and decided to stay, or they were itinerant warriors who actually

helped the Salernitans repel a Saracen (Arab) raid. The Normans were

then asked to stay and did. Or, perhaps, they were simply following

the same Norman nature that sent them out from Denmark centuries earlier,

seeking worlds to conquer. In any event, by the mid-1000s, Robert Guiscard

and a number of his Hauteville clan were firmly entrenched in the south.

They set about taking over, piecemeal, what was left of Lombard holdouts,

Byzantine enclaves, and brigand and pirate hideouts, as well as taking

on the great Arab armies on the island of Sicily.

"Guiscard"

is a by-name meaning "resourceful." Apparently, Robert was given the

name of "Viscardus" somewhat ironically by his first wife's

nephew (1) for knowing whom to marry and (2) for his uncanny ability

to know when to be ruthless and when to be forgiving. There is no doubt

that he had the rough-and-tumble Norman lust for battle, but he could

also be diplomatic. His wisdom extended to not being vindictive in war;

he was not driven by the petty need to brutalize those whom he had defeated.

You fought, you won, and you consolidated, and you do that by turning

enemies into ex-enemies and then into allies. But—here's the very

wise Robert—why wage war against a formidable enemy, Salerno,

when you could merge both your dynasties by marriage? Why not blend

the ancient, noble Lombards of Salerno with the vigorous, warrior Normans?

All you needed was a handsome, robust and willing groom—himself,

and a beautiful, robust and willing bride—Sichelgaita.

There is

no evidence that the young noblewoman, Sichelgaita, was dragged kicking

and screaming into a marriage she detested. Quite the contrary, if sources

are to be believed. Sure, it may have been an arranged marriage of convenience,

and who knows if she was truly smitten, but--for Heaven's sake! -- it

was marriage to Robert of Hauteville, that great, good-looking,

charismatic warrior and the one allmighty walker-on-water figure of

the 11th century in Italy. She, herself, was astute and knew what her

duchy stood to gain by such a union. She had seen the handwriting on

the wall, and it was all writ large in Norman French. Now, at least,

the Norman and Lombards might rule much of Italy together.

The marriage

came about in 1058. It didn't exactly enjoy the blessings of Sichelgaita's

brother, Gisulf, but he, too, was intelligent enough to know that his

duchy could use some friendly Normans in the family. He was beset by

the nearby Duchy of Capua as well as by marauding bands of very unfriendly

Normans under the leadership of Robert's younger brother, William of

Hauteville.

In order

to enter the holy bond of matrimony to his Lombard princess, Robert

had to have his first marriage annulled, which he managed to do by admitting

to incest. Robert and his first wife, a Norman, were nowhere close to

the forbidden degree of kinship that defines incest, but it was a ploy

that worked. Robert took his new, young bride off to his capital city

of Melfi.

The next

18 years of Sichelgaita's life leading up to the siege of her own home

town of Salerno were spent as a constant companion of her husband, helping

him solidify his hold on southern Italy. All accounts of her activities

report that she was his trusted advisor in affairs of state and military

matters. Also, she was very devout, which helped her smooth over Robert's

difficulties with the Church. She was genuinely troubled over the fate

of her husband's immortal soul, since he had the bad habit of getting

himself excommunicated every now and then for his devil-may-care invasions

of Papal land. Sichelgaita's diplomatic skill was crucial in straightening

out many of these thorny problems. On one such occasion, Pope Nicolas

II wound up blessing Robert as the rightful ruler of the land he had

already taken (most of southern Italy), all this in return for Robert's

oath of allegiance to the Pope and the Church.

The Church's

stance vis-à-vis the Normans in the middle of the 1000s

changed from ambiguity to support. Though Stephen IX, Pope in 1057/8,

actually proposed military campaigns against the Normans, he was followed

by Nicolas II, a believer in strong ties to these people whom he no

doubt saw as somewhat of an irresistible force. Then came

Alexander II, noted for approval of that other Norman Conquest, the

invasion of Britain in 1066. Then, of course, came Hildebrand, Pope

Gregory VII, the great reformer, friend of Sichlegaita's, a friendship

that would play a great role in the life of this Pope, one of the most

important in Church history.

The

Arechi castle in Salerno, where the Lombard surrender to the Normans

took place.

When the

time came, as it had to, for Robert of Hauteville to demand the surrender

of Salerno, the last remaining large Lombard Duchy in the South, it

was no doubt his wife who kept him from simply attacking her native

city outright. And, thus, the opening scene of this story came to pass.

Sichelgaita went into the city and begged her brother to surrender.

He wouldn't, so Robert simply lay siege to Salerno and, bluntly, starved

them out. It took months, but it was effective. Sichelgaita's had managed

to save her brother's life. He went into exile in Rome. When the

time came, as it had to, for Robert of Hauteville to demand the surrender

of Salerno, the last remaining large Lombard Duchy in the South, it

was no doubt his wife who kept him from simply attacking her native

city outright. And, thus, the opening scene of this story came to pass.

Sichelgaita went into the city and begged her brother to surrender.

He wouldn't, so Robert simply lay siege to Salerno and, bluntly, starved

them out. It took months, but it was effective. Sichelgaita's had managed

to save her brother's life. He went into exile in Rome.

Interestingly,

the fortunes of Salerno took a turn for the better under the combined

rule of Robert the Wise and hometown princess, Sichelgaita. The medical

school returned to its splendor of old when one of the great itinerant

scholars of the Middle Ages, Constantine of Carthage, called the "African",

was caught secretly wandering around the premises of the medical school,

admiring it. He had seen the great medical schools of Islam, but he

had not seen anything like this, he told Robert—at which point

Robert hired him to teach there. Also, the Lombard-Normans built a new

city wall and a new cathedral.

Robert's

grip on the south of Italy was still shakey, however. His own brothers

--even if they lacked the military might to confront him directly--

often agitated against him. It would be an error to view the Hauteville

Brothers as a united conquering army. Quite the contrary; Robert had

to be everywhere all the time, putting one brother in place and routing

a renegade baron or duke somewhere else.

His ambitions,

however, went well beyond southern Italy. Just as he had woven himself

into the old and venerable Lombard line to fix his grip on the south,

he and Sichelgaita in 1074 had arranged the marriage of their daughter,

Olympiade, into the ruling Dukas dynasty of Constantinople. Such a marriage

would set up Norman rule not just of southern Italy but of the entire

Eastern Roman Empire. It would be a force without equal in Europe. Potentially,

Robert saw, if not himself, then his children as the reuniters of the

recently splintered Christian faith. (The great Schism between the eastern

and western churches had occurred in 1054 when Pope Leo IX and the Greek

patriarch, Michael Cerularius, mutually excommunicated each other.)

There would again be a true empire, and here, some sources say, Robert

spoke of his ambitions to conquer Persia, as had Alexander.

A palace

coup in Greece, however, caused the new Byzantine dynasty to back out

of the proposed merger of dynasties. Robert would have to do it the

hard way, and it is in this adventure that Sichelgaita's reputation

as a warrior is grounded. It is true that on a number of earlier occasions

she had taken the field of battle with her husband. He trusted her to

lead his men and she did so, successfully. But the oft-told story of

the Valkyrie-like blonde berserker --the into-the-jaws-of-death princess,

charging into battle, spitting fire and railing at her men to stand

their ground and fight-- comes from her heroics at the battle of Durazzo

on the Albanian coast in October, 1081. Here the Normans set out to

do militarily what they had failed to do through the diplomacy of marriage:

conquer Byzantium.

The best

description of Sichelgaita in battle on that occasion comes from Anna

Comnena, the daughter of Alexis I Comnenus, the emperor of Constantinople

at the time of Robert's invasion. She writes of the Norman invasion

of Greece in her 15-volume history, The Alexiad, written a few

decades after the events took place. The Norman invasion was massive,

meant as it was to overthrow the rulers of Byzantium. They met forceful

Greek resistance, however, at which point the Norman advance stalled,

one front was commanded by Sichelgaita. Her men faltered, and, here,

Comnena writes admiringly of her ferocious enemy [cited in Norwich,

below in bibliography]:

| Directly

Gaita, Robert’s wife (who was riding at his side and was

a second Pallas, if not an Athene) saw these soldiers running

away. She looked fiercely after them and in a very powerful

voice called out to them in her own language an equivalent to

Homer’s words "How far will ye flee? Stand and fight like

men!" And when she saw that they continued to run, she grasped

a long spear and at full gallop rushed after the fugitives; and

on seeing this they recovered themselves and returned to the fight. |

In spite

of being badly wounded, Sichelgaita fought valiently and held her part

of the battlefield until Robert arrived with reinforcements.

The battle

was won, but the planned takeover of Byzantium had to be shelved. Matters

back in Italy commanded Robert's attention. Relations between the Papal

States and the Empire had taken a turn for the worse. There were two

reasons for this. The first was that Pope Gregory had supported this

invasion of Byzantium by a Norman force friendly to him. He saw it as

a means to bring the Eastern Church back into the fold, and a way to

stem increasing Muslim pressure on Constantinople. (The Seljuk Turks

had recently inflicted a devasting defeat on Byzantine forces, and the

Eastern emperor had already approached Pope Gregory about the possibilty

of launching a Crusade against the Muslims.) Thus, a Norman victory

would be a Papal victory --something that the Holy Roman Emperor could

not tolerate. The second reason for the sour relationship between the

Church and the Empire was Gregory's call for a theocracy in Europe,

one in which the princes and kings of the earth would be subservient

to the Church of Rome.

Whatever

the reason or combination of reasons, the emperor, Henry IV, declared

Pope Gregory VII (photo, left) to be deposed. The emperor invaded Rome

and set up his own puppet "anti-Pope", Clement III. This situation was

dangerous for Robert in the South. He had counted on a strong buffer

state between the Holy Roman Empire and the Norman south. That buffer

was the Church State. Robert had taken great pains in his life to renew

his pledges of loyalty to the Pope and to use Sichelgaita's influence

with the Church and her great diplomatic abilities to stay in the good

graces of the Papacy. He would now have to honor his commitment of loyalty

and free the Pope from the imperial usurpers. These strategic reasons

were reinforced by his wife's closeness to church fathers. She was a

lifelong friend of the archbishop of Salerno, who was a close friend

of Pope Gregory. Robert really had no choice. Whatever

the reason or combination of reasons, the emperor, Henry IV, declared

Pope Gregory VII (photo, left) to be deposed. The emperor invaded Rome

and set up his own puppet "anti-Pope", Clement III. This situation was

dangerous for Robert in the South. He had counted on a strong buffer

state between the Holy Roman Empire and the Norman south. That buffer

was the Church State. Robert had taken great pains in his life to renew

his pledges of loyalty to the Pope and to use Sichelgaita's influence

with the Church and her great diplomatic abilities to stay in the good

graces of the Papacy. He would now have to honor his commitment of loyalty

and free the Pope from the imperial usurpers. These strategic reasons

were reinforced by his wife's closeness to church fathers. She was a

lifelong friend of the archbishop of Salerno, who was a close friend

of Pope Gregory. Robert really had no choice.

At this

point, Robert made one of his few strategic blunders—necessary,

perhaps, but a blunder, nonetheless. He simply lacked the manpower to

take a city such as Rome, defended as it was by an imperial army. To

make up for this lack, he brought in mercenaries, bands of Saracens

(Muslims) still roaming the south. Let that point sink in—he hired

Muslims to invade Rome! The strategy worked, militarily. The imperial

forces withdrew, but the behavior of Robert's troops in the city of

Rome was so outrageous that the entire populace was alienated. Gregory,

himself, was seen as a collaborator of those who were pillaging the

city, and he was forced to flee, leaving the anti-Pope still in charge.

Gregory went to Salerno, where he was welcomed as the "real" Pope. He

died there in 1085, no doubt saddened by his inability to rejuvenate

the Church with his reforms (or, at least, unaware of the great, long-term

moral influence his reign as Pope would have on later Church history).

In 1084,

Sichelgaita again went with her husband to the battlefields of Greece

to try and finish what they had started. They immediately met and defeated

a combined Venetian-Byzanine fleet in a ferocious encounter; they took

the island of Corfu and then Cefalonia. At that point, the story of

Robert of Hauteville, this greatest of Norman conquerors (his better-known

cousin, William the Conqueror, is said to have bolstered his own morale

by thinking of Robert's exploits) comes to a sudden end. After the battle

of Cefalonia, he took ill and died quickly in July of 1085. Sichelgaita

was by his side when he died, and she arranged to have his mortal remains

returned to Italy to rest in the Hauteville crypt in the Cathedral of

Venosa in Puglia.

The

death of Robert left a great question mark hanging over Norman rule

in the south. None of his children had his abilities—nor should

that be surprising. The Norman campaign in Greece fizzled out. Rule

in southern Italy fell, by default, to Robert's brother, Roger I, the

conqueror of Sicily, whose son, Roger II (photo, left), would then become

the founder of The Kingdom of Sicily (later, the Kingdom of Naples).That

kingdom began in 1130 and then passed quickly out

of Norman hands to the German Hohenstaufen line.Through later dynasties,

it lasted until 1860. The

death of Robert left a great question mark hanging over Norman rule

in the south. None of his children had his abilities—nor should

that be surprising. The Norman campaign in Greece fizzled out. Rule

in southern Italy fell, by default, to Robert's brother, Roger I, the

conqueror of Sicily, whose son, Roger II (photo, left), would then become

the founder of The Kingdom of Sicily (later, the Kingdom of Naples).That

kingdom began in 1130 and then passed quickly out

of Norman hands to the German Hohenstaufen line.Through later dynasties,

it lasted until 1860.

Sichelgaita

died in March of 1090 in Salerno, the city of her birth. She had more

or less "retired" after her husband's death and spent much of her time

with her old teachers or in religious seclusion in the Abbey of Montecassino,

a place to which she had a lifelong bond and devotion. She willed that

she should be buried there.

There are

two nasty rumors about Sichelgaita: one, that she had tried to poison

her husband's son by his first marriage and, two, that she had actually

poisoned Robert, himself, after the battle of Cefalonia. She was, after

all, an accomplished student of herbal wizardry from her years at the

medical school in Salerno. Neither of these rumors is given any credence

at all by historians. It all seems to be just more medieval backbiting.

Other than

that, she comes across as somewhat low-key, living, as she did, in the

shadow of her husband, but then bursting forth at times. Her role as

a battlefield fury has lent itself to caricature over the centuries,

which is as unfortunate as it is natural. There is really nothing to

indicate that she was even very ambitious --at least not for herself.

And she was certainly neither conniving nor bent on being the power

behind Robert. She was simply an intelligent and devout woman with diverse

interests—spiritual, scientific, and military—and she was

quite willing to put her considerable skills at the disposal of a cause,

a Lombard-Norman empire. Was she a good warrior? No doubt. By all accounts,

she was a good wife and mother, too. In between her bouts of diplomacy

and battlefield heroics, she managed to bear Robert 10 children.

Bibliography:

Comnena,

Anna. The Alexiad transl. by E. Dawes. Routledge, Kegan,

Paul. London, 1928. More information on this fascinating medieval document

--indeed, the complete text of the Dawes translation-- is available

at

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/AnnaComnena-Alexiad.php

A biographical sketch of Anna Comnena, herself, is at http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01531a.php

Also, a more recent translation (1985) by Sewter has been published

as a Penguin Classic.

Cuozzo,

Enrico. "L'Unificazione normanna e il regno normanno-svevo" in Storia

del Mezzogiorno. Edizione del Sole per Rizzoli.Napoli, 1988.

Delogo, Paolo. "Il Principato di Salerno" in Storia del Mezzogiorno.

Edizione del Sole per Rizzoli. Napoli, 1988.

Norwich, John Julius. The Normans in Sicily. Penguin. London,

1970

Pirenne, Henri. Mohammed and Charlemagne. Dover. Mineola,

2001. Reprint of 1935 edition, George Allen & Unwin, London.

Scozza, Michele. Sichelgaita, Signora del Mezzogiorno. Alfredo

Guida Editore. Naples, 1994.

Sampietrino,

stone-cutting

A sampietrino, in Italian. means various things:

(1) it was a coin minted by the Papal States under Pius VI (Pope from

1775-91) and was worth 2½ baiocchi, a name that apparently

derives from the northern French town of Bayeaux. I have never been

to Bayeaux, but if I go, I shall be sure to take plenty of baiocchi;

(2) it refers to a person charged with tending the premises of San Peter's

Cathedral in Rome (indeed, sampietrino means "little St. Peter");

(3) it means a cobblestone, or paverstone, cut from a dark, fine-grained

igneous rock with the geological name, in Italian, piperno —"trachyte"

in English. I don't know why these cobblestones are called "little St.

Peters," except that it might mean "a stone that looks like the kind

they used when they built St. Peter's—the kind of stone that costs

all those baiocchi." A sampietrino, in Italian. means various things:

(1) it was a coin minted by the Papal States under Pius VI (Pope from

1775-91) and was worth 2½ baiocchi, a name that apparently

derives from the northern French town of Bayeaux. I have never been

to Bayeaux, but if I go, I shall be sure to take plenty of baiocchi;

(2) it refers to a person charged with tending the premises of San Peter's

Cathedral in Rome (indeed, sampietrino means "little St. Peter");

(3) it means a cobblestone, or paverstone, cut from a dark, fine-grained

igneous rock with the geological name, in Italian, piperno —"trachyte"

in English. I don't know why these cobblestones are called "little St.

Peters," except that it might mean "a stone that looks like the kind

they used when they built St. Peter's—the kind of stone that costs

all those baiocchi."

The sampietrino—the

cobble-stone—is ubiquitous in Naples. It provides one of the two

major stone colors in the city, the other being the lighter yellow of

tufa, stone so porous that walls made from it will erode and have to

be replaced in a few decades. But piperno is durable and many

main roads are still laid by workers with small hammers, tapping one

fist-sized sampietrino after another into place, mile after mile,

and then drip-sealing the cracks with hot tar. Asphalt has made major

inroads (thank you) only with great difficulty. That will change shortly,

according to a report in the paper. Asphalt is cheaper, safer, and faster

to work with. The paper gave no date, but soon that friendly clatter

as your car slowly jars itself to smithereens over those miles of treacherous

trachyte along the port road of Naples will belong to another age.

There will

still be no shortage of sampietrini in Naples. All of the many

stairs that lead up and down the hillsides of Naples are made of Little

St. Peters, the piperno pockmarked with centuries of chisel strikes

to roughen the surface so that the stairs are less slippery in the rain

and so you don't slide those 200 meters of elevation from the Vomero

hill down to the center of town.

The dark

stone comes from hills of Naples. The suburb of Naples called "Soccavo"

sits below the height of the Camaldoli hill and takes its name from

the Latin subcavum—beneath the quarry. For centuries, stonecutters

quarried that hillside to extract not just tiny paving stones, but the

true monoliths used at the base of almost all Neapolitan monuments,

large buildings, and churches. The stone was then loaded onto ox-carts

that plodded their way into the city a few miles away. The Spanish moved

quarries well away from the city in the 17th century out of concern

for the structural integrity of the hill that much of Naples rests upon;

thus, the quarries of Soccavo closed. There is, however, still a large

cross hewn from that same material standing on a street corner in Soccavo

(photo, above). It was originally a religious object, certainly not

uncommon on the streets of Naples, but today (protected recently by

a display case) it is also, because of the material it is made of, a

monument to the bygone craft of stone-cutting. It bears the engraved

name of the artisan who made it and the date, 1613.

Vico, Giambattista

(1668-1744)

Statue

of Vico in the Villa Comunale.

If you

were born shortly after the death of Rene Descartes, you came of age

during the great blossoming of Rationalism and the study of the natural

sciences. If you were interested in philosophy, it would not be

at all surprising if you had turned out to be a true child of

the Enlightenment, one whom history might group into that vast

body of thought encompassed by such thinkers as Descartes,

Spinoza and Voltaire. Giambattista Vico, however, did not quite fit

in with the spirit of his times, and that is precisely why he

is interesting. If you

were born shortly after the death of Rene Descartes, you came of age

during the great blossoming of Rationalism and the study of the natural

sciences. If you were interested in philosophy, it would not be

at all surprising if you had turned out to be a true child of

the Enlightenment, one whom history might group into that vast

body of thought encompassed by such thinkers as Descartes,

Spinoza and Voltaire. Giambattista Vico, however, did not quite fit

in with the spirit of his times, and that is precisely why he

is interesting.

He was

born on the street in Naples known as 'Spaccanapoli' and lived there

most of his life. After his university studies and a few years of travelling

around teaching, he wound up as a professor at the University of Naples, a post he held until his death.

His thoughts are contained primarily in his Autobiography

and in Principles of a New Science of Nations.

Vico was

at odds with the prevailing climate of the eighteenth century, which

felt that truth about the universe could be arrived at rationally.

This idea of a 'clockwork' universe, a mechanism entirely accessible

to human understanding, remained so persausive that by the late 19th

century prominent scientists were all set to dot the last 'i' of the

last law of physics and declare that discipline defunct. Then along

came our own century with such things as Relativity, Uncertainty Principles,

Quantum Indeterminacy, and Gödel's Theorem. Kurt Gödel showed

that mathematics—and, hence, logic—was not the perfect standard

of precision that it had appeared to be.

Two centuries

earlier, Vico, completely out of step with his contemporaries,

had not been comfortable with the Aristotelian ideal of perfect deduction

from first principles and had said that even mathemathics did not—could

not—contain the certainty that philosophers such as Descarte would

have liked. The so-called "truths" of mathematics were true only because

the rules governing mathematics were man-made and arbitrary. Thus,

Vico was somewhat of a harbinger of revolutionary twentieth-century

scientific philosophy.

Something

else that made Vico different from his fellow philosophers was the emphasis

he placed on the study of history.To someone like Descartes, history

was little more than a messy collection of human absurdities, hardly

the stuff worthy of true scientific enquiry. To the extent that Enlightment

philosophers worried about the nature of society, it was, again, to