©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

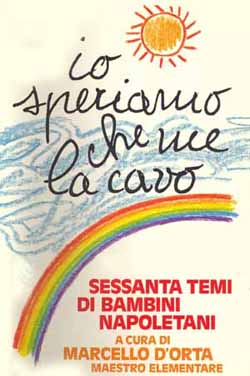

Io

speriamo che me la cavo

One

of the most popular books in Italy in recent years was written by an

elementary school teacher, Marcello D'Orta, in the small town of Arzano

near Naples. It was published in 1990 by Arnoldo Mondadori and is entitled

Io speriamo che me la cavo. The title is, one, ungrammatical

Italian and, two, is the heartfelt wish of the schoolchild who wrote

the essay from which the title of the book is taken. It says: "I hope

I pass". The entire book, in fact, is a collection of 60 such essays

written by Mr. D'Orta's charges in the 10 years he was a teacher at

the school. One

of the most popular books in Italy in recent years was written by an

elementary school teacher, Marcello D'Orta, in the small town of Arzano

near Naples. It was published in 1990 by Arnoldo Mondadori and is entitled

Io speriamo che me la cavo. The title is, one, ungrammatical

Italian and, two, is the heartfelt wish of the schoolchild who wrote

the essay from which the title of the book is taken. It says: "I hope

I pass". The entire book, in fact, is a collection of 60 such essays

written by Mr. D'Orta's charges in the 10 years he was a teacher at

the school.

In presenting

the children's essays about, among other things, their favorite films,

their dreams (real and metaphorical), where they would go if they could

travel, their home lives, and what they would do if they were millionaires,

D'Orta says, in the introduction, that he tried to avoid falling into

the trap of "Eduardoism" (in reference to Eduardo de Filippo)—that is, to avoid

an overly staged presentation of every poor schoolchild from Naples

as if that child were a scugnizzo, a street urchin, trying out

for a film. They're not, he says. They're just kids who write with the

simple honesty and insight that children bring to their observations.

The teacher left the ungrammatical title in its original form and, by

and large, left most of the errors in the short essays intact. (In a

translation, of course, that element is almost impossible to render,

and, in what follows, I have not tried to do so.)

One sample:

| Your

teacher talked about Switzerland. Can you summarize the most important

points?

Switzerland

is a small country in Europe that borders on Switzerland, Italy,

Germany, Switzerland and Austria. There are a lot of lakes and

mountains, but there isn't any ocean, especially in Bern.

Switzerland

sells arms to the whole world so they can kill each other, but

Switzerland doesn't ever have even a small war. They build banks

with all their money. But not good banks. The banks are for

bad persons, especially drug addicts. Criminals from Sicily

and China put their money in these banks. The police go and

ask, Whose money is this? and they say I don't know, I'm not

going to tell you, it's none of your damn business, the bank

is closed. But the bank is really open!!

In

Naples, if you get cancer, you die, but in Switzerland you die

later or maybe you live. Because the hospitals are beautiful.

They have carpets, flowers, the stairs are clean and there are

no rats. But you pay a lot of money. Unless you sell stuff on

the black market, you can't afford to go.

Is

this long enough?

|

In 1992,

Italian film director, Lina Wertmüller, made the book into a film

with the same title as the book. The English rendering of the title

is as good as possible, which is not very: "Ciao, Professore."

Actually, the term "ciao" is informal and wouldn't be used by

pupils to a teacher, which fact might make the title not bad since it

is inappropriate language, just like the title of the book. Unfortunately,

most English-speakers who view the film don't know about that subtlety

of Italian and think that "ciao" means, simply, "Hello," which

it doesn't. The film stars the great comic Paolo Villaggio as the teacher

and centers on his character, a teacher from the north of Italy who

winds up, through a computer error, assigned to just such a small school

in the Neapolitan outback. Of course, he can barely understand the native

Neapolitan dialect of his pupils. His learning to understand them and

their problems at home (descriptions of which are taken direcly from

the book), is the charm of the film.

Donizetti,

Gaetano

(1797-1848)

With

Rossini and Bellini,

Donizetti is one of the important names in early 19th-century Italian

opera and a founder of Italian Romanticism. He was born in Bergamo.

After initial musical studies, he was commissioned to write two short

works that were performed in Venice in 1818. He also wrote sacred

music and several string quartets. One work, Zoraid di Granata,

composed in 1821 and performed in Rome caught the ear of Domenico

Barbaja, Neapolitan impresario, who invited him to compose for Naples,

a city where Rossini was already active and thriving and where Bellini

was just starting out.

Donizetti

moved to Naples in 1822 and stayed for 16 years. Today, a plaque on

his home in Naples quite ignores his operas and reminds us that he was

the composer of Ti voglio bene assaje, the winner in 1835 of

the first Festival of Piedigrotta for the Neapolitan

popular song. The piece is still a mainstay of that repertoire.

It is typical of his approach to his work, in general, that he would

write music at the drop of a hat —early comic operas, later

serious melodrama, and, here, even popular songs. (Interestingly, as

the illustration shows, he was often in such a hurry to write music

that he availed himself of his rather unusual form of ambidexterity

--writing with both hands at the same time!)

He composed

La zingara in 1822 and at least 5 other operas before 1830, including

works for La Scala in Milan. He spent a year in Palermo in 1826 and

then returned to Naples where he became the director of the Teatro

Nuovo. He became the director of the Royal Theaters in Naples in

1828 and held that post for 10 years.

Donizetti

was a prolific and fast composer, turning out 30 operas before he can

be said to have "made it" with Anna Bolena in 1830. A partial

list of his more well-known works, still very much part of the operatic

repertoire, includes Elisir d'Amore (1832); Lucrezia Borgia

(1833); Lucia di Lammermoor (1835); La figlia del regimento

(1840); and Don Pasquale (1843). Much of his work in Naples in

the 1830s was subject to typical censorship by the absolutist Bourbon monarchy, particularly allergic to undue

violence or allusions to royalty and unhappy endings—particularly

restrictive in an art form that was well on its way to a reputation

for thriving on tragedy. Lucrezia Borgia was, in fact, banned

in Naples. He left Naples in 1838, at least partly due to the restrictive

atmosphere he was forced to work in. He moved to Paris and then to Vienna

where he became court composer to the Austrian emperor. By the early

1840s, Donizetti was seriously ill with syphilis. He moved back to his

hometown of Bergamo in 1848 and died there.

Musically,

like other composers of his generation, he was a product of the influence

of the Neapolitan comic opera. Yet,

Romanticism had arrived and there is no doubt that Donizetti is one

of its founders, particularly when the hallmarks of Romanticism —human

passion and struggle—were freed from the confines of censorship.

He had what would become the Romantic flair for slow, plaintive melody,

typified, say, by "Una furtiva lacrima" from Elisir d'Amore (still

one of the best-loved of all operatic arias), yet, untypically, never

at the expense of the text. He was known for bickering with his librettists

over their choice of words. He had somewhat of a professional rivalry

with his contemporary, Bellini, and, perhaps, in historical terms, can

also be said to have overshadowed the great Italian influence of the

early 1800s, Rossini, who became less and less active as the century

became more and more Romantic.

With historical

hindsight, it is interesting to read music reviews from, say, 1850,

that wondered whether the young upstart, Verdi, would ever amount to

another Donizetti. The year of Donizetti's death, 1848, was also the

year of the great wave of revolutions that swept Europe, demanding a

corresponding artistic expression more emotional and turbulent than

even Donizetti could ever have imagined.

Capri

(4)

I

called up Herman the other day to see if had attended last week’s

ceremony commemorating the Anglo-American invasion at Salerno. It took

place 60 years ago and Herman, who is now 87 years old, was part of

it. He told me that he hadn’t attended, though he had spoken with

some members of the US 36th infantry who had stopped by to say hello

to him in Sorrento. The ceremony in Salerno was marked by some counter-demonstrations

by those who feel that remembering anything at all to do with war and

violence is a bad thing, even when it’s on behalf of the good

guys. I

called up Herman the other day to see if had attended last week’s

ceremony commemorating the Anglo-American invasion at Salerno. It took

place 60 years ago and Herman, who is now 87 years old, was part of

it. He told me that he hadn’t attended, though he had spoken with

some members of the US 36th infantry who had stopped by to say hello

to him in Sorrento. The ceremony in Salerno was marked by some counter-demonstrations

by those who feel that remembering anything at all to do with war and

violence is a bad thing, even when it’s on behalf of the good

guys.

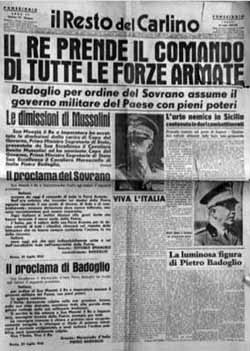

September

1943 was turbulent and confusing for Italians. The nation surrendered

to the Allies on September 8, at which point Pietro Badoglio, who had

succeeded the deposed Mussolini as head-of-state in July 1943 (newspaper

headline photo), declared that the war would now continue on the side

of the Allies and against the Germans and Italian Fascists. That plunged

Italy into a civil war.

The armistice

of September 8 provided a strange episode—amusing in hindsight—having

to do with the Isle of Capri. There were about 2500 members of the Italian

Armed Forces on Capri at the time of the armistice. Obviously, they

were now all part of the Allied command at war with their old allies,

the Germans.

Part of

the terms of the armistice required the Italian naval contingent on

Capri to move to Palermo, in Sicily. The Italian commander was unable

to comply with the order because there simply wasn’t enough fuel

left to run the ships that far. He sent a motorboat over to the Gulf

of Salerno to advise the Allied commander of the situation; that is,

the Italian forces on Capri weren’t making any sort of a Fascist

last stand on Capri, nor were they refusing to surrender. They just

had no fuel for the ships.

Accordingly,

on September 12, an Allied ship showed up at Capri to check out the

situation. The Allied commander then—for reasons that are as obscure

as they are silly—demanded a separate “unconditional surrender…

[from] the Commanding Officer of the Axis Armed Forces on the Islands

[sic] of Capri.” (The Allied commander may have been counting

the Faraglioni, those two beautiful rocks 100 yards off shore

as separate islands.)

In a true

Laurel and Hardy finish to the episode, the surrender document—written

in both English and Italian—was signed improperly. The Allied

officer signed on the wrong side of the page, leaving the Italian no

choice but to sign in the name of General Eisenhower.

Soccer

(5)

Since

I last mentioned the topic (here), someone

has managed to patch up the disastrous situation in the Italian soccer

leagues. Naples was on the verge of being relegated to the C-League

on the basis of a legal decision about the validity of a signature on

a document. That decision was appealed and overturned, which left some

people happy, others unhappy, and almost everyone confused. No one seemed

to know which teams would go down to the C League and which would be

promoted to the B League. As a result of that confusion, several of

the B League teams refused to play their opening matches two weeks ago. Since

I last mentioned the topic (here), someone

has managed to patch up the disastrous situation in the Italian soccer

leagues. Naples was on the verge of being relegated to the C-League

on the basis of a legal decision about the validity of a signature on

a document. That decision was appealed and overturned, which left some

people happy, others unhappy, and almost everyone confused. No one seemed

to know which teams would go down to the C League and which would be

promoted to the B League. As a result of that confusion, several of

the B League teams refused to play their opening matches two weeks ago.

The situation

was resolved by trying to make everyone happy; that is, no one would

go down to the C League—the B League would just be expanded

to include all the would-have-been demotees. So far, so good. Alas,

the teams that didn't play the first week have started out somewhat

in the hole in the league standings. The scoring rules give a team 3

points for a victory, 1 for a draw and 0 for a loss. The fine print

also reads "loss of a point for a forfeit"—that is, refusing

to play in the first place. Thus, some teams started out this season

with a minus 1. So maybe not everyone was happy, but I did say, "patch

up".

Pizza

(3)

The

scene was the Mostra d'Oltremare,

the Overseas Fair Grounds in Naples. Since last I wrote about it, at

least the arena, the spacious outdoor theater, has been renovated and

is once again ready to host large-scale productions, maybe even Aida,

just like in the good old days. The

scene was the Mostra d'Oltremare,

the Overseas Fair Grounds in Naples. Since last I wrote about it, at

least the arena, the spacious outdoor theater, has been renovated and

is once again ready to host large-scale productions, maybe even Aida,

just like in the good old days.

The event

in question last week was a bit less ambitious, but still worthy of

mention. It was Pizzafest 2003, a pizza cook-off to choose—and

what better judges than Neapolitans? —the world’s greatest

pizzaiolo, or pizza chef.

Without

further ado, may I have the envelope, please. Ahem. The third-place

winner is Luigi Picariello from Naples. (Ho-hum.) The second-place winner

is Antonio Langella from Naples. (Please hold your applause and ho-hums.)

And the world’s greatest pizza chef is—Makato Inishi from

Japan! (I told you to hold the ho-hums.)

That’s

right. In a fair cook-off, the 23-year-old Japanese young man beat all

comers. He came to Naples two years ago for the express purpose of learning

the art of pizza cooking, and seems to have done rather well. I don’t

know if he is the gentleman I mentioned elsewhere,

one sent here with an interpreter to learn the pizza trade. It wouldn’t

surprise me, but on the other hand, I have heard that there are at least

a few such visitors from Japan in Naples. In any event, there were no

sour grapes (not an authentic topping, anyway) on the part of the Neapolitans.

They seemed happy that they had taught Makato so well.

This is

perverse, I know, but somehow I am reminded of the scene in Doctor

Strangelove where Sterling Haden, as deranged general Jack D. Ripper,

asks RAF officer Mandrake (played by Peter Sellers) if he had been tortured

by the Japanese when he was their prisoner in World War II.

“Yes,”

says Mandrake. “I don’t understand. They make such bloody

good cameras.”

San Gennaro

(3)

Silver

bust of S. Gennaro donated by Charles II of Anjou in 1305, in the Naples

cathedral.

Yesterday,

of course, was San Gennaro, the feast

day of the patron saint of Naples. On this day, the faithful anxiously

await the miraculous liquefaction of a vial of the saint’s clotted

blood. This “Miracle of San Gennaro,” if it comes to pass,

is regarded as a good omen for the city of Naples in the year to come.

Yesterday, the faithful who waited in the Cathedral of Naples, where

the ceremony surrounding the event takes place, were rewarded early

in the day. At 9.57 a.m. Cardinal Michele Giordano held up the vial

and announced that the miracle had, indeed, transpired. Yesterday,

of course, was San Gennaro, the feast

day of the patron saint of Naples. On this day, the faithful anxiously

await the miraculous liquefaction of a vial of the saint’s clotted

blood. This “Miracle of San Gennaro,” if it comes to pass,

is regarded as a good omen for the city of Naples in the year to come.

Yesterday, the faithful who waited in the Cathedral of Naples, where

the ceremony surrounding the event takes place, were rewarded early

in the day. At 9.57 a.m. Cardinal Michele Giordano held up the vial

and announced that the miracle had, indeed, transpired.

One newspaper

headline reported “A lightning miracle in a fortified cathedral,”

referring to the security measures in place to avoid potential disruption

by a nearby demonstration of the unemployed, all of whom would have

liked to get in and bend the ear of the mayor of Naples, Rosa Russo

Iervolino, or the president of the Campania Region of Italy, Antonio

Bassolino, both of whom were in attendance.

A special

section of the daily, il Mattino, dedicated a series of short

articles to various aspects of the phenomenon of San Gennaro, including

items perhaps not generally known to Neapolitans, themselves. For example,

San Gennaro was made the patron saint of Naples in 472 a.d. during an

eruption of Mt. Vesuvius as powerful as the one that had destroyed Pompeii

400 years earlier. Naples had always had a history—even before

the advent of Christianity—of making appeals to the gods. Naples

had so many temples to Greek and Roman gods that Quintilia, a figure

in the Satyricon (written in 60 a.d.) says: “We have so

many gods that they’re easier to find than people.” San

Gennaro, himself, was preceded as patron saint of Naples by, among others,

Saint Agrippino, but when the eruption hit and thousands of Neapolitans

crowded into the catacombs where San Gennaro was entombed, and beseeched

him to save them from the impending disaster, he—well, he apparently

did. The eruption stopped and Gennaro has been the patron saint ever

since.

With one

exception. He expressed approval of the Neapolitan Republic in 1799

by performing his miracle at the behest of the French commander of the

forces supporting the Republican cause. In retaliation, the Army of

the Holy Faith, the Royalist Neapolitans, later retook the kingdom under

the banner of Saint Anthony. But that was a temporary lapse.

The first

mention of the miracle of blood liquefaction is from 1389. The paper

reports on attempts of skeptics to fabricate (using 1389 technology)

a liquid that looks like solid blood and will liquefy when shaken (yes,

it can be done). Also, there is an account of the adventures of Giuseppe

Navarra, the so-called King of Poggioreale, a hustling junk merchant,

who in 1947 took it upon himself to go to Rome and bring back the treasures

of San Gennaro from the Vatican, where they had been moved for safekeeping

during World War II.

These treasures,

by the way, include a collection of gold, silver, and diamond artifacts

of incalculable value. The will all be on display shortly in a brand

new museum of The Treasures of San Gennaro to be inaugurated later this

year by the President of Italy, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi.

Elsewhere,

in a book entitled Napoli Antica by Vincenzo Regina (pub. Newton

and Compton, Rome, 1994), I came across a strange tale of San Gennaro.

It used to be the custom for a “relic” of the saint (in

this case, part of the skull) to be transported from the Cathedral to

a local seggio, a seat of local government within the city—a small

town hall, as it were—on one of the days when the miracle was

supposed to occur (there are a few other days besides September 19.)

At day’s end, the relic would be duly transported back to its

place in the cathedral. Representatives of the local seggio always provided

transportation. They would show up at the Cathedral, pick up the relic,

take it away and bring it back. In 1646, however, the good folks in

the Cathedral refused to hand over the relic and insisted on doing the

moving, themselves. During the procession, they were assaulted by the

locals and a good-sized fistfight broke out over who had the authority

to escort San Gennaro’s skull.

Normans,

the

The

Other Norman Conquest The

Other Norman Conquest

By the

year 1000 Italy south of Rome was a hodge-podge of Lombard duchies plus

a number of small city-states such as Naples as well as various Byzantine

provinces; there was also a massive Arab presence on Sicily and the

southern mainland. Into this already complicated setting rode the Normans,

only a few generations after wading ashore in France as the justifiably

feared warrior-race, the Vikings.

Now, the

nicest thing ever said about the Vikings was that, yes, they were ferocious,

cunning and absolutely ruthless—completely given to pillaging

and plundering—but not because they liked it! It was because

they realized that ruthless pillaging and plundering was the most efficient

way to get what they wanted: namely, the property and possessions of

others.

If the

Vikings were only half as nasty as their reputation, it is little wonder

that within 150 years of their first raids on Britain and the continent

they had maneuvered the French king, Charles the Simple into the wise

move of ceding to them in 911 the land in the north of France which

would become known as Normandy, named for them, the Northmen or Normans.

The real wonder of it all is that they decided to settle down, and even

more wondrous was that in a few generations' time, all their fire and

rage would be diluted by southern climes, and their empire in southern

Italy would be known for its tolerance, culture and laid-back way of

life. But that is precisely what happened.

If you

stand in front of the royal palace in

Naples and look at the statues of the rulers of the city, Roger II,

the Norman, is the first one (photo, above). He is the monarch who represents

the beginning of modern history in Naples. He was the beginning of what

might be called a European dimension in southern Italy.

The feudal

redistribution of land in Normandy had meant that a number of young

Norman knights wound up with nothing, so they sought their fortunes

elsewhere. By the early eleventh century, bands of them were already

wandering around this area, fighting for anyone who would pay them --Lombards,

Byzantines, the Papacy, the Dukes of Salerno, Capua or Naples. In return

for helping the Neapolitan Duke, Sergio IV, in 1029, they were given

the hill-fortress in Aversa with its dependencies, and that area soon

became a jumping off point for Norman adventurers who wished to take

part in the struggles going on for control of the south. In the middle

of the eleventh century they were fighting for and against everyone,

managing to take over piecemeal much of what had been Lombard land.

By 1090 they had taken Sicily from the Arabs.

Robert

of Hauteville arrived in 1047. He was described as very tall with eyes

that all but emitted sparks and a voice that put his enemies to flight.

His ambition and lust for adventure are said to have been an inspiration

to William ("the Conqueror") back home and so, at least second hand,

he may have played a part in the invasion of Britain in 1066. [The Naples

Web Log entry about Robert's wife, Sichelgaita,

is also relevant.]

The Papacy,

originally glad to have Norman help against the Byzantines and Lombards,

realized that the Norman tail was now wagging the Papal dog. Normans

were raiding monasteries in Italy with as much abandon as had their

Viking grandfathers a few generations before in Britain and France.

The Normans consolidated their gains in a victory over the combined

Papal forces of Lombards, Italians (from the Papal States) and German

mercenaries at Benevento in 1054. The Pope as well as the Western Empire

were forced to ratify Norman gains. It was a brilliant move by the Normans:

they now pledged allegiance to the Church, in return for which, of course,

the Papacy consecrated the Norman Empire in the South, now virtually

all in Norman hands, anyway.

By 1060

there were three separate Norman holdings: Aversa, Capua and Apulia,

the last of which was the most important, because it was from there

that the Normans, under Roger I, (Robert's brother) went on to take

over Sicily and, by default, all Norman holdings in the South.

Shortly

after William the Conqueror had successfully invaded Britain, Robert,

who saw himself as eventual lord of the whole Mediterranean went on

to try and mop up the entire Byzantine Empire in Greece, and failed.

His less ambitious sibling, Roger, stayed on in Sicily. Roger's third

son became Roger II, and was crowned King of Sicily in 1130.

Roger II

marched north in a campaign to unify Sicily with the southern Italian

mainland. He entered Naples in September 1140. Story has it that he

got on the good side of his Neapolitan subjects immediately by calling

them together and asking them how long the city wall was. No one knew,

so he personally marched it off at 2,373 paces and announced that he

was going to enlarge it for the good of Naples and it citizens.

The city

thus lost its independence, but gained a king who called himself Rex

Siciliae et Italiae, and membership in an ambitious empire, one

with designs on North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. The capital

was Palermo, one of the richest and most opulent cities of the day,

efficiently and benevolently ruled by a mixed aristo-burocracy of Greeks,

Sicilians and Arabs. It was a place where your god, language and race

took a back seat to whether or not you could get the job done. For a

brief period, the overused phrase "Golden Age" truly applied to this

empire, as the collective voices of centuries of Mediterranean cultures

joined together almost as if to announce the coming of the Renaissance

Roger died

in Palermo in 1154, and a few years later the Norman Kingdom of the

South fizzled out because of lack of male issue. One of Roger's granddaughters

had married the son of the German emperor Barbarossa. Their child would

become Frederick the II and, thus, the

Kingdom of Two Sicilies would pass to German rule.

It was

a strange end for the Normans. In the South they were victims—fortunate

ones, perhaps—of their own flexibility. They started out

as almost caricatures of themselves: ferocious, aggressive, asking no

quarter and certainly giving none. They wound up as a blend of cultures,

languages and faiths, a society apparently ruled by "an aristocracy

of talent" (to use Thomas Jefferson's choice phrase) In hindsight, coming

as it did on the eve of that atrocity known as The Crusades, their rule

here seems to have been one of the last great periods of understanding

and tolerance in European history, one in which there was a fortunate

and rare reversal of the roles described by Yeats: This time it was

not "the worst," but "the best," who were "full of passionate intensity".

America's

Cup (2), urbanology (7)

The

plans to “deindustrialize” the Bay of Pozzuoli are ambitious.

The area includes the town of Bagnoli and extends west along the coast

through Pozzuoli, itself, and on to the end of the bay at Cape Miseno.

The long-term plan, one assumes, is to try to resurrect the natural

beauty of the area with an eye for attracting some of the considerable

money generated by the tourist trade elsewhere in the Gulf of Naples—that

is, Naples, the Sorrentine peninsula, and the islands of Capri and Ischia. The

plans to “deindustrialize” the Bay of Pozzuoli are ambitious.

The area includes the town of Bagnoli and extends west along the coast

through Pozzuoli, itself, and on to the end of the bay at Cape Miseno.

The long-term plan, one assumes, is to try to resurrect the natural

beauty of the area with an eye for attracting some of the considerable

money generated by the tourist trade elsewhere in the Gulf of Naples—that

is, Naples, the Sorrentine peninsula, and the islands of Capri and Ischia.

It’s

a tall order, but they have started. This week, they started the end-stage

demolition of the remains of the old Italsider steel mill, for many

decades a thriving enterprise as well as an unsightly blob of industrial

blight in Bagnoli. As well, the Sofer plant in Pozzuoli has been closed.

It was one of the oldest industrial concerns in the Naples area, having

been built 120 years ago, not too long after the unification of Italy.

For over a century it turned out railway coaches and engines.

These few

steps into the post-industrial age are independent of—but somehow

connected psychologically with—another ambitious project: attracting

the next America’s Cup regatta to the waters of Bagnoli, off the

tiny island of Nisida. Scarcely a day goes by without an update in the

papers. Within the next few months, the Swiss defenders of the Cup will

make their decision as to where they wish to defend their title, and

Naples, it seems, stands a reasonable chance of being selected. Money

has been found, marine architects hired, plans for the new harbor are

on the boards. The design presents what the papers have been calling

a “canal harbor”; that is, using the large area that used

to contain the facilities of the Italsider steel mill, a long rectangle

will be cut in from the sea, one end of which is, obviously, the outlet

to the bay, with the perimeter of the other three sides providing mooring

for boats.

It will

be a shot in the arm for the area if the Swiss choose these waters and

that kind of ambitious boat harbor is built. Even if Naples loses out

in the America’s Cup lottery, however, the other plans—the

ones to turn the area into the kind of place that people will actually

want to visit and enjoy—will continue.

Metropolitana

(4)

There

is a famous postcard of the Bay of Naples seen from the Posillipo hill

above Mergellina. It’s the classic view: the waters in front of

the Villa Comunale and the seaside road, via Caracciolo,

the Castel dell’Ovo, and the double peaks of Mt. Vesuvius

and its companion, Mt. Somma, in the background with the beginnings

of the Sorrentine peninsula spreading to the south. The photo is usually

taken such that there is a famous, solitary Mediterranean pine tree

in the foreground. There

is a famous postcard of the Bay of Naples seen from the Posillipo hill

above Mergellina. It’s the classic view: the waters in front of

the Villa Comunale and the seaside road, via Caracciolo,

the Castel dell’Ovo, and the double peaks of Mt. Vesuvius

and its companion, Mt. Somma, in the background with the beginnings

of the Sorrentine peninsula spreading to the south. The photo is usually

taken such that there is a famous, solitary Mediterranean pine tree

in the foreground.

We used

to joke that the reason they used that same tree all the time was that

it was the only one left in Naples. That is, of course, an exaggeration,

since, as I have pointed out elsewhere, there are a number of large

parks in Naples: the Villa Comunale, the Floridiana, the

grounds of the Capodimonte museum, and the vineyards of San

Martino. Those parks don’t change the fact, however, that

your average neighborhood trees, the ones that line the street in front

of your house, little by little, over the years, can’t help but

lose the battle with encroaching, egregious overbuilding. We need a

garage—those trees go. An extra parking space or two?—chop,

chop. (Forget the downright forests sacrificed to illegally built, entire

blocks of flats.)

Thus, I

am unhappy and suspicious when I read that 60 (!) trees have been chopped

down in Fuori Grotta to accommodate construction sites for the new underground

train line coming in from the area of the new university and San Paolo

football stadium. “New underground train line” is,

of course, ridiculous. That is the train that was supposed to be up

and running in 1990 for the World Cup soccer matches (see here). Now that incompetence and bribery have

been relegated to the rubbish heap of history, the train line (officially

to be known as Line #6) will be finished and joined to the main lines

of the metropolitana in Naples. This has meant performing quintuple

by-pass surgery on the one main road, viale Augusto, that leads

through that section of town, creating a labyrinth of one-way detours

to get from one end of the road to the other, one mile away. Of the

30 palm trees that were there a few days ago, 8 are still there; the

other 22 have been moved, but shall be returned. Sixty pines, however

got the axe. The city promises that they will replaced by 94 new ones

when the construction is finished. City promises—well, they are

what they are.

Bellini

(Piazza) (2)

Persons

described in the morning paper as “Neapolitan intellectuals”

have written an open letter to the city administration protesting the

proposed renovation of Piazza Bellini ( also

see separate entry). Persons

described in the morning paper as “Neapolitan intellectuals”

have written an open letter to the city administration protesting the

proposed renovation of Piazza Bellini ( also

see separate entry).

I am always

amused by the definition of people as “intellectuals,” as

opposed to just plain “intelligent” or even “very

intelligent”. It makes you wonder if “intellectual”

is a profession or, at least, an official position. Maybe they have

a guild, union or club you can join where you get an ID card or decoder

ring and learn a secret handshake—all contingent upon your oath

that when others go bowling with the boys on Wednesdays, you go deconstruct

Kierkegaard and smoke French cigarettes.

Whatever

the case, this time they are right. The charm of Piazza Bellini is that

it is cockeyed and a bit seedy. Is it dirty? Yes, it can be, but that

condition, says the letter, won’t be helped by getting rid of

the irregular, bleacher-type irregularities that make you step up once

or twice and then down again as you cross the square. If you level the

square and turn it into the planned black-and-white checkerboard design

with a shallow platter-shaped fountain in the middle (with no water!),

put in a single central palm tree (after getting rid of all the other

trees), and even out the staggered entrances to the “literary”

cafes that open onto one side of the square—if you do all that,

you will then have a useless and inappropriate bit of urban surgery

that will have cost the city 700 thousand euros—and it will still

get dirty.

Why not

leave the square the way it is and just clean it regularly? Also, clean

the statue of the square’s eponym, Vincenzo Bellini. The statue

is the target of graffiti vandals and has been so abused over the years,

that the four secondary busts of women from the composer’s operas

have had to be removed from the niches that surround the base of the

central figure of Bellini, himself. (In the course of the removal and

transfer to God knows where, one of the busts disappeared.

Modernization

is not the answer to everything, says the letter. The city modernized

the Villa Comunale and no one likes it (what happened to all the trees?);

the city modernized Piazza Dante after the recent subway construction

and turned it into wide-open flat space with no shade and very few places

to sit. And so forth and so on. Spend the money on regular maintenance

and Piazza Bellini will be just fine.

Street

life (descriptions)

In another

entry I refer to the “cascade of chaos” in the

pages of Harper’s Weekly in a description of Neapolitan

street life from the mid-1800s. (A short excerpt, as a reminder):

| …water-sellers

bawling iced water; pious minstrels playing doleful bagpipes under

a statue of the virgin; Sicilian girls dancing the tarantella

with uncommon vigor; friars roaring that they only want a gran

more to save a soul from hell; boys fighting for watermelons;

exchange tables loaded with copper; lemonade-stands mounted by

triumphal arches, bedizened with gold paper and wreathes of flowers;

macaroni-dealers ladling huge masses of the smoking delicacy out

of cauldrons, and beseeching the crowd not to let it cool; more

monks tinkling little bells, and knocking Punch and the conjuror

over as they hurry past with a dead man… |

I enjoy

comparing that with similar passages from other sources—famous

ones—from around the same time. Here is a short passage from Pictures

of Italy by Charles Dickens: (Click

here for the entire excerpt.)

| …for

all Naples would seem to be out of doors, and tearing to and fro

in carriages. Some of these, the common Vetturino vehicles, are

drawn by three horses abreast, decked with smart trappings and

great abundance of brazen ornament, and always going very fast.

Not that their loads are light; for the smallest of them has at

least six people inside, four in front, four or five more hanging

on behind, and two or three more, in a net or bag below the axle-tree,

where they lie half-suffocated with mud and dust. Exhibitors of

Punch, buffo singers with guitars, reciters of poetry, reciters

of stories, a row of cheap exhibitions with clowns and showmen,

drums, and trumpets, painted cloths representing the wonders within,

and admiring crowds assembled without, assist the whirl and bustle.

Ragged lazzaroni lie asleep in doorways, archways, and kennels;

the gentry, gaily dressed, are dashing up and down in carriages

on the Chiaji, or walking in the Public Gardens; and quiet letter-writers,

perched behind their little desks and inkstands under the Portico

of the Great Theatre of San Carlo, in the public street, are waiting

for clients... |

And one

from The Innocents Abroad by Mark Twain: (Click here for the entire excerpt.)

| …I

will observe here, in passing, that the contrasts between opulence

and poverty, and magnificence and misery, are more frequent and

more striking in Naples than in Paris even. One must go to the

Bois de Boulogne to see fashionable dressing, splendid equipages,

and stunning liveries, and to the Faubourg St. An-toine to see

vice, misery, hunger, rags, dirt -- but in the thoroughfares of

Naples these things are all mixed together. Naked boys of nine

years and the fancy-dressed children of luxury; shreds and tatters,

and brilliant uniforms; jackass carts and state carriages; beggars,

princes, and bishops, jostle each other in every street.

At

six o’clock every evening, all Naples turns out to drive

on the Riviera di Chiaja (whatever that may mean); and for two

hours one may stand there and see the motliest and the worst-mixed

procession go by that ever eyes beheld. Princes (there are more

princes than policemen in Naples - the city is infested with

them) - princes who live up seven flights of stairs and don’t

own any principalities, will keep a carriage and go hungry;

and clerks, mechanics, milliners, and strumpets will go without

their dinners and squander the money on a hack-ride in the Chiaja;

the rag-tag and rubbish of the city stack themselves up, to

the number of twenty or thirty, on a rickety little go-cart

hauled by a donkey not much bigger than a cat, and they drive

in the Chiaja; dukes and bankers, in sumptuous carriages and

with gorgeous drivers and footmen, turn out, also, and so the

furious procession goes. For two hours rank and wealth, and

obscurity and poverty, clatter along side by side in the wild

procession, and then go home serene, happy, covered with glory!…

|

Today,

it is still possible to catch a carriage ride if you are a tourist and

want to pay whatever exorbitant fare they charge for clip-clopping along

the seaside on via Caracciolo—a street that did not exist

in the mid-1800s; however, some of the romance goes out of the experience

amid the din of cars, motor-scooters, and all-around roar of technology.

It’s a tough call, but on a bad day in modern Naples, those descriptions

from the 1800s sometimes seem almost bucolic.

Anticaglia,

via—

One

of most fascinating things about a palimpsest would be to use some of

that new-fangled multispectral imaging and be able to see what was actually

written on the layers below the surface. Who knows, you might wind up

in ancient Greece. (I understand that is precisely what has happened

at a museum in Baltimore, where they have found Archimedes’ Theory

of Floating Bodies floating well below the surface of some medieval

scribbling. One

of most fascinating things about a palimpsest would be to use some of

that new-fangled multispectral imaging and be able to see what was actually

written on the layers below the surface. Who knows, you might wind up

in ancient Greece. (I understand that is precisely what has happened

at a museum in Baltimore, where they have found Archimedes’ Theory

of Floating Bodies floating well below the surface of some medieval

scribbling.

Archaeologically

in Naples, there is no doubt a palimpsest phenomenon at work. All you

have to do is dig a station for the metro almost anywhere near sea level

in the city and you uncover, first, some Spanish walls and, sooner or

later, bits and pieces of ancient Rome and Greece. It happens all the

time.

Those without

personal steam shovels may have to settle, however, for a kind of “horizontal

palimpsest” effect. That is, wander around town and look for bits

of Rome still stuck somewhere in a façade, arch, wall or tower.

Such bits are easy to overlook, and most people never notice them for

the simple reason that much of this ancient masonry is in a part of

the old city that almost no one frequents; that is, the upper decumanus,

via Anticaglia.

There were

three main decumani in Greco-Roman Naples; that is, three main

east-west streets. The bottom two are well known to anyone who has spent

any time at all in Naples, or, indeed, even to those who may visit just

for a day or two. They are the two streets that everyone “just

has to see”: the bottom one is called, colloquially, Spaccanpoli,

and starts (at the west end) at the great Church of Santa Chiara; the

second one (the central decumanus) is via dei Tribunali

and starts (at the west end) at the music conservatory and adjacent

Church of San Pietro a Maiella. The upper decumanus—the

one no one ever strolls along—is known as via Anticaglia (though

it changes names a few times as it runs through the old city).

Via

Anticaglia is so little known because the entire area where it used

to start at the west end of the old city was razed in 1900 and rebuilt

to accommodate the vast premises of the Naples medical school and Polyclinic

hospital now situated between the central decumanus, via dei

Tribunali the upper decumanus, via Anticaglia.

An entire medieval convent belonging to the order of Carmelite Sisters

was removed as the hospital grounds built their way up the steep hill

between the central and upper decumanus. Additionally, the area

to the west along the old Greek and Roman wall, approximately the line

followed by today’s via Costantinopoli contained a number

of buildings such as the church and convent of Santa Maria della

Sapienza. Those, too, were removed. Finding the western entrance

to the upper decumanus, then, entails hiking up the cross street

from the central decumanus as if you were on your way to the

medical school. At a certain point, you turn right (east) and wander

down again into the old city.

The first

thing that you notice is that there are no tourists. It is almost eerily

lonely at times. In a way, you feel as if you have gone back at least

a century in time. Then, as you approach the halfway point—the

main north-south street (called a cardine), via San Gregorio Armeno,

coming up from the right (south) as it runs along the side of the church

of San Paolo Maggiore— you notice the “horizontal palimpsest”

effect, Roman masonry, indeed, an entire Roman arch still in place and

helping to hold someone’s house up (photo). This is the area of

the ancient Roman open theater.

The theater,

they say, was still discernible until the 1400s, when most of it was

razed or buried in order to build the great church of San Paolo Maggiore.

The theater was, in every respect, comparable to those that you can

still see today in Pompeii and Herculaneum—100 meters long and

seating for thousands. More so than those towns, Neapolis was the theatrical

big-time in this part of Italy, playing satire, tragedy, even a comedy

written by Claudius and—if they had neon signs, this would have

lit them up!—Nero, himself! Yes, the emperor fancied himself quite

a nimble finder on the lyre and fancied that he had a fine voice. (He

also fancied that he was a good emperor). Anyway, he would sing and

play in Naples while luminaries such as Seneca were in the audience,

presumably trying very hard not to laugh (“Please, Jupiter, let

me keep a straight face!”)

Via

Anticaglia has other interesting points of history as you follow

it out to the east to via Duomo. At the corner of via Gigante,

is the site where a Jesuit college was founded in 1552 by disciples

of Loyola, himself, the founder of the order. Tarquato Tasso, the Sorrentine

poet lived in this part of Naples for a while and attended the college.

Giambattista Vico, too, lived in the same area. The entire street, end

to end, is off the beaten track, but worth the time to wander along.

Bourbons

(3)

The

Coming of Garibaldi

[Parts

1 and 2 are here and here, respectively.]

The

fall of the House of Bourbon and the Kingdom of Naples in 1860

is part of the success of the risorgimento, the movement to

unite Italy into a single nation. This success is due primarily to

three persons: a theoretician, a politician, and a soldier. The

fall of the House of Bourbon and the Kingdom of Naples in 1860

is part of the success of the risorgimento, the movement to

unite Italy into a single nation. This success is due primarily to

three persons: a theoretician, a politician, and a soldier.

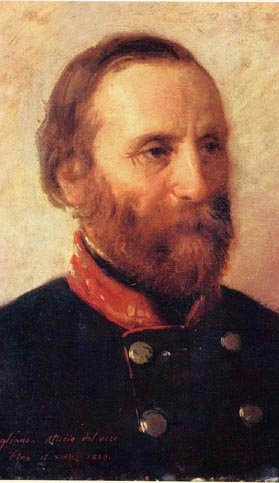

The theoretician,

the ideologue, the one who preached national unity, was Giuseppe

Mazzini (1805-72). He was not a particularly practical man, and he spent

much of his life in exile, proclaiming from abroad the idea of Italian

unity as a fulfillment of destiny, one which he apparently saw as a

nebulous combination of ancient Italian glory and reasonable aspirations

to modern nation-statehood.

The politician

of the risorgimento, a person as shrewd as Metternich and Bismark,

was Camillo Benzo Conte di Cavour (1810-61) the prime minister of the

Kingdom of Piedmont. Northern Italy in the mid-1800s was a patchwork.

There was Piedmont, Lombardy, Modena, Venezia, the Papal States, etc.

etc., each a sovereign state. It was Cavour who had the political acumen

to handle the problem of northern unity before turning to the greater

one of unifying north and south. He was, however, a conservative and

calculating man, one who favoured a gradual process of unification over

revolution.

The politician

Cavour might have had his way if the soldier, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-82),

as a young man in the 1830s, had not wandered into a tavern where the

theoretician, Mazzini, was holding forth to fellow members of the revolutionary

group, Young Italy.

| "What

do you mean by Italy?" asked one. "The Kingdom of Naples? The

Kingdom of Piedmont? The Duchy of Modena?"

"I

mean the new Italy… the united Italy of all the Italians,"

said Mazzini.

|

"At that

point," recalled Garibaldi in later years, "I felt as Columbus must

have felt when he first sighted land."

As a pirate,

patriot, soldier of fortune, lover and guerilla fighter from Italy to

South America, Garibaldi had a patent on the swashbuckle. He survived

imprisonment, torture, severe wounds and exile. As a general, he was

fearless, commanding respect and loyalty from his men by fighting

right alongside them in hand-to-hand combat. He was a man of action

with an acute sense of justice and a childlike belief that good would

triumph over immorality and corruption. He didn't want to win battles

for politicians —he distrusted them. He was simply and truly

out to smite evil. He was what most twelve-year-old boys want to be

when they grow up, and if you ever have a strange dream in which you

are beset by enemies and plagued by wrongdoers, and your dreammeister

lets you choose whomever you want for help, take Garibaldi. Ask

Cavour and Mazzini. They took him, and they didn't even like him. He

was that good.

Thus, in

May of 1860, Francis II, King of the Two Sicilies had excellent reason

to worry. Garibaldi, over the objections of the ultra-cautious Cavour,

had just smuggled a small and almost unarmed (!) group of men out of

the port of Genoa aboard two leaky tubs and set off to liberate

the Italian south. He would start in Sicily, in support of a local uprising,

and work his way over to the mainland and on up to the capital, the

city of Naples. He cajoled and threatened weapons and ammunition out

of the commanders of a few armories along the way as he plodded south

toward Sicily, where his famous "Thousand redshirts" (1,089, to

be exact) would take on a regular army twenty times that number.

The Kingdom

of the Two Sicilies had a sizable army and the largest navy in the Mediterranean.

Socially and politically, however, it had been standing still since

the post-Napoleonic Restoration in 1815, surviving the Carbonari revolution of 1820 and successfully resisting

calls for reform only by being propped up by the Austrian army and Swiss

mercenaries. Many of the kingdom's liberals and intellectuals had left,

and by 1860 even King Francis could sense what was coming. In June of

that year (after Garibaldi had already taken Sicily!) he revived

the constitution of 1848 and relinquished his absolute powers. There

was even talk of an alliance between a liberalized Naples and the Piedmont

kingdom of northern Italy—an Italian federation, of sorts. This,

indeed, would have been a watered-down risorgimento, but

it would have thwarted Garibaldi.

Even northern

politicians, primarily Cavour, while theoretically in favor of Italian

unification, were aghast at the thought of a popular revolutionary army

led by a thousand redshirted lunatics storming up the peninsula, spreading

a message of instant universal brotherhood. Garibaldi, after all,

in his youth had had to do with a mystic band of Christian communards,

the St. Simonians, who, years before Karl Marx, had preached:

From each according to his capacity: to each according to his works;

the end of the exploitation of man by man; and The abolition of all

privileges of birth.

Garibaldi

landed at Marsala and a few days later engaged a superior force

near Calatafimi. He threw caution to the winds (he didn't have very

much of it, to begin with), said, "Here we either make Italy or die",

and led a ferocious bayonet charge uphill, literally overrunning the

enemy.

And that

was more or less that. Sicilian irregulars in rebellion against the

royal forces had been watching the engagement from nearby hillsides.

They liked what they saw. Soon Garibaldi's forces were swelled by a

ragtag collection of rebels armed with guns, axes, clubs and whatever

else could kill a Bourbon. Together they marched on Palermo and by ceaseless

guerilla street fighting drove the Bourbon commander into asking for

an armistice, the only condition being that royalist forces be allowed

to leave the island for the mainland.

With 3,500

men under him, Garibaldi then crossed to the mainland and started the

300-mile slog in the heat of summer up towards Naples, his reputation

preceding him by leaps and bounds. Peasants were already calling him

the "Father of Italy," mothers brought their babies out to be

blessed by him, and there was an air of natural invincibility about

him as he moved north.

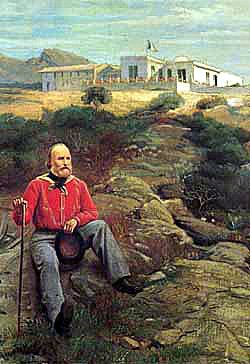

Garibaldi

at his home on the island of Caprera in Sardinia

There is

much discussion even today about exactly how a relatively small band

of Garibaldini, augmented at most by a few thousand irregulars

picked up along the way, managed to make their way up the peninsula

against what, at least on paper, appeared to be an overwhelmingly superior

force. It is probably best to view Garibaldi's victory as resulting

from a combination of factors. First, Garibaldi, himself, was a master

of the hit-and-run harassing tactics that would one day become known

as "guerilla warfare." He was also a firm believer in Napoleon's dictum

that "morale is to material as ten is to one"—and his Redshirts

had morale to burn. They were the righteous bringers of a new nation,

and there is little doubt that large numbers of the long-suffering peasantry

in Calabria and Puglia (perhaps less so as he moved further north towards

Naples) genuinely viewed them as liberators. There is

much discussion even today about exactly how a relatively small band

of Garibaldini, augmented at most by a few thousand irregulars

picked up along the way, managed to make their way up the peninsula

against what, at least on paper, appeared to be an overwhelmingly superior

force. It is probably best to view Garibaldi's victory as resulting

from a combination of factors. First, Garibaldi, himself, was a master

of the hit-and-run harassing tactics that would one day become known

as "guerilla warfare." He was also a firm believer in Napoleon's dictum

that "morale is to material as ten is to one"—and his Redshirts

had morale to burn. They were the righteous bringers of a new nation,

and there is little doubt that large numbers of the long-suffering peasantry

in Calabria and Puglia (perhaps less so as he moved further north towards

Naples) genuinely viewed them as liberators.

The confused

situation in the Bourbon military also worked to Garibaldi's advantage.

There was massive desertion among royalist troops, many of whom felt

that they were now bound up in defending a lost cause. Additionally,

the officer corps had been bitterly split for at least a decade between

old-guard royalists and those who felt that the time for a united Italy

had come at last.

All this,

and more, combined to produce the unlikely sight, on September 7, 1860,

of Giuseppe Garibaldi and a small group of companions entering Naples

unopposed, by train (!) from Salerno and then in an open carriage from

the station to the Royal Palace. They were miles ahead of the

army. The king had fled to Gaeta the day before and the city and remaining

troops welcomed the Risorgimento by giving Garibaldi a hero's

welcome.

A Bourbon

force of about 20,000 troops had remained loyal to the king and

gone north with him. Initially, the king had intended his retreat as

somewhat of a strategic withdrawal. He had no intention of surrendering

his kingdom without a fight. His army, near Gaeta, was, however, also

being pressed from the north by the advancing army of King Victor Emanuel

of Piedmont, who had finally decided to get on the bandwagon of unification

before Garibaldi got all the credit. Thus hemmed in, the Bourbons made

a desperate effort in early October to break out and retake their kingdom

by storming south at the Volturno River. Garibaldi was called upon for

one of the few times in his life to fight a pitched battle instead of

one of his guerilla actions, and to defend instead of attack. He commanded

troops along a twenty-kilometer front against a superior attacking force

and held.

On October

25th, near Capua, Garibaldi greeted Victor Emanuel of Piedmont's Royal

House of Savoy with the words, "Greetings to the first King of Italy"

and surrendered his conquests—Sicily, half the Italian peninsula

and the vast Neapolitan Royal Navy (considerably superior to northern

Italian fleets of the time)—without the slightest hesitation or

thought of reward for himself—simply because it was the right

thing to do.

For their

efforts, Garibaldi and his superb men were completely and utterly snubbed

by the new rulers of Italy. The egalitarian initiatives such as free

education and land reform that Garibaldi had set up during his brief

reign as "Dictator of Naples" were revoked, provoking for another

decade in much of the south what almost amounted to a civil war as recently

liberated subjects of the Bourbons took to the hills to escape their

liberators from the north.

Garibaldi

didn't like the way things had turned out, but figured it was just more

injustice he would have to straighten out when he got around to it.

He spent the last twenty years of his life actively trying to do just

that in one way or another, in one place or another. He would fight

more battles, be arrested and imprisoned (he escaped) and even be elected

to parliament. He didn't have a political bone in his body, and he continued

to be saddened and confounded by the politics of those who refused to

do the right thing. The Kingdom of Naples, which Garibaldi had handed

to Victor Emanuel on a silver platter, was officially dissolved on Oct.

22, 1860, when Neapolitans voted by plebiscite to become part of Mazzini's

"new Italy…united for all Italians".

The

last military action by the Bourbons against the armies of united Italy

was as heroic as it was useless. After the battle of Volturno, Francis

II and his faithful men and officers retreated to Gaeta, circled the

wagons and prepared to go down fighting. From November 1860, to February

1861, the city was subjected to a ferocious bombardment. Without the

slightest chance of withstanding a siege, much less ever getting their

kingdom back, and with no ulterior strategic goal, the Bourbons of Naples

resisted and fought the way brave men do who have nothing to lose. Napoleon

III of France implored them to give up, as did even the attacking Italian

commander, Bersaglieri commander Cialdini, who said that he would be

honored to fight against such valiant troops if it weren't a case of

Italian against Italian.

After 8,000

of his men had fallen in the siege, the King told those who wanted to

leave to do so. Almost no one left. Histories of the siege are replete

with truly moving accounts of the young queen Maria Sophia on the ramparts, herself, encouraging

the defenders and refusing to eat so that her food could be given to

the wounded. Apparently, when honour had been satisfied, for one can

think of no other reason, Francis agreed to surrender. He and his wife

went to Rome as guests of the Pope. When the Papal State fell in 1870,

they settled in Paris. He died in 1894, his wife in 1925.

The Bourbon

dynasty was the high point as well as the end of the existence of southern

Italy as a separate nation. Today, 140 years after the irresistible

Risorgimento (bearing in mind, of course, that judgements about

"irresistible" are always easier after the fact) forcibly incorporated

The Kingdom of Naples into greater Italy, it is still difficult to draw

dispassionate conclusions that balance the former existence of the South

as a separate and respected European state against the subsequent advantages

as part of a single greater nation.

There

is a good 19th-century political cartoon plus accompanying article from

Harper's Weekly about Garibaldi's conquering of the Kingdom of Naples

at

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/harp/0707.php

Immigration

(4)

The terms

“multicultural” and “multiethnic” present a

certain paradox when thinking about Naples. At times, looking at the

long history of the city, it seems that it must have always been a grand

mixture of different peoples. When the Spanish first got here in the

1500s, for example, Spanish soldiers, officers, diplomats, and merchants

suddenly occupied most of the area near the Royal Palace. That is the

area still known as “The Spanish Quarter”. Of course, there

are no Spanish there, any more. Whatever was separately and distinctly

Spanish about the area is now totally Neapolitan. Taking that which

is foreign and making it your own is very characteristic of Naples.

The Spanish experience has surely been repeated many times over the

centuries. Naples seems to be a giant blender that homogenizes whatever

might start out to be separate and distinct elements in society. Thus,

it is, yes, multicultural, but then very quickly Neapolitan.

The Naples

daily, il Mattino, uses the term “multicolor” to

describe the relatively new phenomenon of immigrant children in Naples

attending local public schools. Naples has never been a racist culture,

so the journalist uses such terms quite innocently. She is merely describing

what for her is new and fascinating when she writes about a little girl

as “three–and–a–half years old, a tiny thing

with grand eyes, wearing a rose-colored checkered school blouse that

contrasts with her coal–black skin.”

The Neapolitan

public school system is now dealing with the fact that Naples, for whatever

reason, is home to thousands of immigrants. They may be newly arrived

refugees from eastern Europe, au pair from almost anywhere in the world,

African street vendors, or Rom—gypsies.

Children

of these persons are required to attend school. Last year, 2,825 immigrant

children registered for elementary schools in the Campania province,

of which Naples is the capital. The trend seems to be about a 20% increase

per year. More than half, 1650, were registered for elementary schools

in the city of Naples, itself. Caserta had 750 and Salerno 200. One

particular school in Naples actually qualifies for a special state subsidy

since more than 10% of the student body is immigrant. “So far,”

says the principal, “we haven’t seen a cent.”

The consensus

among teachers is that there are no problems having to do with a pupil

being of a different race. (That is gratifying, but I would have predicted

that.) There are the same language problems, especially with older students

(say, above the age of 12) that you find almost anywhere in the world

in schools where children are suddenly required to learn a new language.

Socially, there is some problem in getting parents in particularly intransigent

immigrant groups such as gypsies to send their children to local schools

in the first place. Volunteers regularly go out into the community to

try to convince these parents to do what is best for their children.

Blackout,

rainfall

Of

natural and manmade catastrophe

About two

weeks ago, Naples had its worst rainfall in living memory. The report

was of a downpour at the rate of four inches an hour. That didn’t

keep up for an hour, but for the 15 or 20 minutes that rain fell like

that, it was impressive, indeed. The rain then eased off to a solid

one inch an hour for much of the day.

Rain like

that—or anything even remotely like that—always causes problems

in Naples. There are two main concerns: one is that the city sewers

can’t handle the run-off. As a result, streets are flooded. Indeed,

down at sea level at the small port of Mergellina, streets were turned

into lakes as a result of rain water flowing downhill from the Posillipo

hill directly above the harbor. The second concern is for the structural

integrity of the subsoil. The large hill that much of the city rests

on is honeycombed with natural and manmade caverns (mostly manmade,

from centuries of quarrying). Every time it rains heavily, some piece

of the city, somewhere, is almost guaranteed to cave in.

The rain

caused some damage to the San Carlo Theater. The drainpipes that are

supposed to get water off the roof of the theater—even when they

are in perfect, unclogged condition (apparently they weren’t)—couldn’t

begin to cope with that amount of water. The damage seems to be minor,

limited at first appraisal to some minor staining of the fresco by Cammarano

on the great ceiling of the theater. The water had to flow somewhere,

so it seeped into the cracks on the roof and found its way through to

the ceiling.

The big

disaster, of course—and this happened just yesterday—is

totally manmade. Well, it was apparently caused by someone or something

in Switzerland. Maybe a cow backed into an Automatic Teller and Milking

Machine (conveniently situated in every pasture in the country for all

your financial and dairy needs) and set off some sort of a Rube Goldberg

chain-reaction. In any event, all of Italy was blacked out for almost

an entire day. Much worse than the great loss to the economy was the

general feeling of disappointment on the part of many Italians at no

longer being able to laugh up their sleeves at the electrotechnologically

backward United States for that blackout a few weeks ago in the northeast.

The only

place in Italy that was unaffected was the delightfully self-sufficient

island of Sardinia, where I happen to be at the moment. I am very happy

not to have been in Naples during a major blackout. It happened at 3

o’clock in the morning, so there weren’t that many people

trapped in elevators. (What were they doing up at that hour?) Fortunately,

the metropolitana—the subway train line—doesn’t run

all night.

I have

never been trapped in the elevator in my apartment house. Now, if my

wife or any other Neapolitan actually knew that I had just written that

sentence, they would go through a series of ritual movements and oaths

to pacify the power that I have just challenged. I have evoked the possibility—nay,

the certainty—just by mentioning it. I don’t believe in

all that, so I say, go ahead, Elevator God, take your best shot.

Santa

Chiara, church (2)

A ceremony was held in the city hall the other day in

memory of (1) the destruction of the church

of Santa Chiara in 1943 and (2) the rebuilding of that church, completed

over ten years later. That rebuilding is responsible for the odd feeling

you get when you stand in the courtyard and stare at the plain masonry

and stark, Gothic architecture of the church: Santa Chiara seems at

once as old as it is and, yet, much newer. It is both. A ceremony was held in the city hall the other day in

memory of (1) the destruction of the church

of Santa Chiara in 1943 and (2) the rebuilding of that church, completed

over ten years later. That rebuilding is responsible for the odd feeling

you get when you stand in the courtyard and stare at the plain masonry

and stark, Gothic architecture of the church: Santa Chiara seems at

once as old as it is and, yet, much newer. It is both.

On August

4, 1943, after 95 previous air raids on the city of Naples aimed primarily

at military installations near the port and train station, the next

attack accidentally hit the church and, as they say here, “destroyed

six centuries in ten seconds.” (Robert of Anjou built the original

church in 1310.) The fire burned for 10 days; 159 persons were killed

and 228 were wounded. The church was left a burned-out shell. The belfry

on the grounds (photo, left) is the only part that escaped destruction.

A plaque (photo, below) on the front of the church, itself, commemorates

the reconstruction, finished in 1953.

The

mayor of Naples attended the ceremony in the presence of young Franciscan

monks, born many years after the event. The ceremony was a tribute to

the reconstruction and, as well, to Brother Gaudenzio Dell’Aia,

the monk who planned and supervised the work. The church was restored

to its original Gothic state, undoing the architectural additions of

those who came after the Angevins in the history of Naples. Luigi Ortaglio,

the Franciscan who succeeded Dell’Aia as the head of the order

in Naples, spoke at the ceremony and called the reconstruction a symbol

of the “victory of peace over war” and compared it to resurrection,

the rebirth that follows death.

The plaque (photo) reads: After centuries of glory this

temple destroyed by war rises as an altar of peace in the heart of ancient

Naples and welcomes the names and memory of those who shed blood in

the hope of love among nations.

August 4, 1943 August 4, 1953

back to subject index

back

to napoli.com

|