©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Copyright (1), Music (1), Neapolitan

Song (1), 'O sole mio

A couple

of items in the Neapolitan daily, Il Mattino, caught my eye yesterday.

One has

to do with the song, 'O sole mio. A judge in Torino has decided

that one Alfredo Mazzucchi (1878-1972) deserves to be listed as a co-author

of that song, along with the traditional authors, lyricist Giovanni

Capurro (1859-1929), and Eduardo di Capua (1865-1917), who composed

the melody.

Mazzucchi

is obscure even to students of the Neapolitan Song and is usually referred

to as a "transcriber," meaning that, as a young pianist, he would show

up and work at the keyboard to help the "real" songwriters get their

ideas down on the black and white of piano keys and music manuscript.

His descendants brought suit, claiming that he had had as much to do

with many of di Capua's famous melodies as did di Capua, himself. The

judge agreed, saying that Mazzucchi's contribution to the "creative

process" is "indistinguishable" from that of di Capua, the person traditionally

regarded as the composer of the melody to 'O sole mio' . The

decision extends, as well, to 18 other popular Neapolitan songs composed

by di Capua, including Maria Marì (commonly known as Ohi,

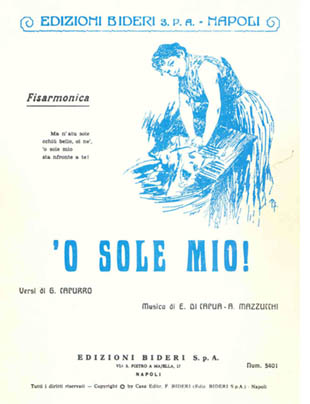

Marì). The decision is reflected in the music credits on

the title page of the music in more recent editions (photo). Mazzucchi

is obscure even to students of the Neapolitan Song and is usually referred

to as a "transcriber," meaning that, as a young pianist, he would show

up and work at the keyboard to help the "real" songwriters get their

ideas down on the black and white of piano keys and music manuscript.

His descendants brought suit, claiming that he had had as much to do

with many of di Capua's famous melodies as did di Capua, himself. The

judge agreed, saying that Mazzucchi's contribution to the "creative

process" is "indistinguishable" from that of di Capua, the person traditionally

regarded as the composer of the melody to 'O sole mio' . The

decision extends, as well, to 18 other popular Neapolitan songs composed

by di Capua, including Maria Marì (commonly known as Ohi,

Marì). The decision is reflected in the music credits on

the title page of the music in more recent editions (photo).

Di Capua's

descendants at first contested the suit, but then backed off, perhaps

in light of the interesting copyright implications. 'O sole mio

is one of the most recorded songs in the history of the industry, but

neither Capurro nor di Capua made real money from it, having sold the

song for a one-time fee of 25 lire to Bideri, the music publishing house.

In any event, since copyright lasts 70 years beyond the death of the

composer --in this case, the last surviving coauthor, Mazzucchi-- the

song is no longer in the public domain and is protected by copyright

until 2042.

The Società

italiania autori e editori (SIAE, the Italian Society of

Authors and Editors) is the Italian version of ASCAP and takes care

of paying royalties in these cases. It will now be deciding how many

millions are to be divided which way among how many persons. I'll have

to ask a copyright lawyer, but I imagine that royalties will be retroactive,

though I don't see how Capurro's or di Capua's descendants will get

anything since both of those authors sold their original rights. (Gee,

I seem to remember showing up at Cole Porter's house one time with a

couple of tunes...)

Among the

many stories surrounding 'O sole mio, perhaps the strangest has

to do with the 1920 Olympic Games held in Antwerp, Belgium. The conductor

of the band couldn't find the music to the Royal March, the national

anthem of Italy, so he struck up 'O sole mio! After a few moments

of confusion, the crowd got the idea and stood up.

(There

was a great typo in the Il Mattino article: the Italian name

for Antwerp is "Anversa". The text referred to "the 1920 Olympics in

Aversa..." [sic]. Aversa is a small town north of Naples, most famous

as the one-time site of a notorious hospital/prison for the criminally

insane. This kind of error is not at all uncommon in the local papers.

Some years ago, one writer for Il Mattino called Princess Grace

of Monaco a "Bavarian Princess". Besides referring to the principality

on the French Riviera, "Monaco" also happens to be the Italian name

for Munich. That, of course, was not a typo -- just stupidity.)

(For more

on the Neapolitan Song, see here and here.)

The second

item in the paper that interested me was the fact that the city has

apparently run out of its printed stock of traffic ticket forms. This

is why no tickets have been written for two weeks and, no doubt, why

I got away Scot-free with doing something really illegal in my car the

other day. I intend to take advantage of this for as long as possible.

Immigration

(1)

I

had an interesting discussion last night with the gentleman who runs

the little bar down at the corner. It was about the Nobel Prize this

year for physics. One of the winners was Riccardo Giacconi, an Italian

who has been living in the US for the last 40 years. I

had an interesting discussion last night with the gentleman who runs

the little bar down at the corner. It was about the Nobel Prize this

year for physics. One of the winners was Riccardo Giacconi, an Italian

who has been living in the US for the last 40 years.

Italy,

it seems, drives away --as immigrants-- not just the "tired, poor and

huddled masses," but great numbers of doctors and scientists. The classic

case, of course, was Enrico Fermi (photo), who went to America in the

1930s to protect his Jewish wife from Fascist Italy's racial laws.

Giacconi

said in an interview that he had left Italy in order to be able to work,

meaning that even as an up-and-coming young physicist in Italy it was

simply too hard to fight a system that keeps you from getting anywhere

unless you are somehow "connected". The guy at bar says that things

haven't changed much and trotted out numerous stories from his own experience.

He liked

my own favorite story. I ran into a young Italian doctor one time who

had just come back from an internship in the US. He told me that on

his first day in the US he was strolling on the campus of the university

hospital where he was going to be working, when an "old guy" yelled

at him from across the way: "Hey, do you play tennis?" He did and wound

up as the doubles partner of the "old guy" -- who happened to be head

of the hospital. Young doc was made to feel totally at home and welcome,

which amazed him and continues to amaze most Italians I tell that story

to. The idea that a person at the top would befriend someone just starting

out is, well, not something that happens here. In the words of the guy

at the bar, "You climb over people to get to the top and then try to

keep people from climbing over you."

Advertising (2), English usage

Enough

ESL (English as a Second Language), EFL (English as a Foreign Language),

and ESP (English for Special Purposes)! I am going to start a school

for EBL (English as a Broken Language) and use the billboard ads near

my house as a text.

First of

all, if you advertise it in English, that fact, alone, says something

like, "We are international," "We are fashionable," "We appeal to the

cosmopolitan person of today". It is entirely in keeping with the de

facto presence in the New Europe of English as an international language.

The French don't like this, but that's tough.

OK, the

one in the photo (above) is correct. But on an adjacent billboard is

a picture of a woman shaving her legs. (Only my 19th-century sense of

propriety keeps me from letting you see it!) Actually, all you see is

the woman from the hips down. She is seated and you see the bottom part

of the "fashionable" pair of shorts she is wearing. A red brand label

is visible on the shorts. Then, you don't see all of the legs, just

the part she is shaving, the upper thigh. Her delicate hand is holding

an equally delicate-looking but very modern, abstract razor that

looks like it could double for some gizmo on Star Trek. Before I saw

the text, I thought it was an ad for women's razors. Silly me. Then,

I look at the text below the ad. It reads:

No superfluous. Just Exyn. Fashion and Blue Jeans Collection.

It's all

in English. The incorrect form "no" for "not" is in the original. (In

English, "no" negates a noun, as in "No Smoking". "Not" negates an adjective,

as in "Not superfluous". In this case, Italians commonly think that

"no" is used in both cases in English. It is part of their version of

"international English". It is also the same as the Italian word "no",

to mean the opposite of "yes". It is close enough to what would be the

correct Italian negative, grammatically, in this case: "non". The word

"superfluous" is equally similar to the Italian form, "superfluo". In

Italian, thus, the expression would be "non superfluo". Why say it in

English? Well, "We are international," "We are fashionable," "We

appeal to the cosmopolitan person of today". They are selling fashionable

clothes, so it fits. If they were selling toilet plungers, probably

not. The ad continues with "just". That's not Italian, but close

enough to "giusto" to have a dual-language pun. "Giusto" means "correct"

in Italian and that might be called up in the mind of an Italian reading

the ad.

The last

part, "Fashion and Blue Jeans Collection" is fascinating. I am old enough

to remember when blue-jeans were not fashionable. They were regarded

as work clothes. You put them on to go work or play rough. "Don't wear

your good pants! Put on those old jeans!" Mommy used to say. The idea

that jeans would someday be included in a "collection" never would have

occurred to me: "Presenting Armani's new collection of Autumn jeans

at the Grand Hotel," or something like that, still amazes me. Jeans have

been elevated in a way that other American cultural icons such as rock

'n' roll and fast-food have not --that is-- elevated to a state of elegance.

This may have to do with the Italian love of the "bella figura" -- looking

good. It has nothing whatsoever to do with whether or not blue-jeans

are functional clothing. In any event, jeans are part of the cultural

invasion by the United States of the rest of the world.

So -- nothing

superfluous. The woman is shaving what is obviously superfluous pubic

hair below the line of her fashionable shorts. Whether or not a woman

shaving up there is (1) necessary, or (2) fashionable, an ad like this

works, obviously, only in those places that make cultural assumptions

about what hair is desirable and where. Message: there is nothing

superfluous about our line of clothing, either. Just Exyn: non-superfluous,

functional but good-looking and fashionable clothing.

Libraries

(1)

There

is only one really public library in Naples -- the National Library,

housed in the Royal Palace (photo).

Once you get past the guard and metal detector, then deposit in a tiny

locker anything extraneous on your person, such as bags and artificial

limbs, then leave the perfunctory retinal scan and urine sample, it

is no more difficult to get in than driving nails with your skull. There

is only one really public library in Naples -- the National Library,

housed in the Royal Palace (photo).

Once you get past the guard and metal detector, then deposit in a tiny

locker anything extraneous on your person, such as bags and artificial

limbs, then leave the perfunctory retinal scan and urine sample, it

is no more difficult to get in than driving nails with your skull.

Much of

the interesting material to read in Naples is held in private or university

libraries. Perhaps the strangest collection is the "La Pegna Mobile

Library" --nearly 200 boxes stored in an ex-chapel near Piazza San Domenico

Maggiore-- now converted into the Brancaccio section of the main National

Library. Each box is crammed with envelopes, each of which contains

carefully clipped out newspaper and magazine articles from the early

decades of the 20th century. The entire collection is arranged alphabetically

by subject and is the result of one journalist's (named La Pegna) obsession

with cataloguing everything he could find from the popular press of

the day. He poured his life into clipping and filing, clipping and filing.

Unfortunately, there wasn't enough room in the library to store all

the stuff, so much of it was "removed" -- a euphemism for "thrown out".

Yet, what remains is fascinating.

Monasteries

I see that

the university my wife graduated from here in Naples has started a new

degree program in art restoration. That is a good idea in a city with

as much art and history as Naples has. They have so much that it is

easy to notice the small run-down churches, closed for centuries; and

the newspapers never seem to tire of reporting how this monument is

falling apart or that building is crumbling. Yet, much of the time,

they do a good job of using their past. I am amazed, for example, at

the great number of the city's public buildings, universities, hospitals

--and even police stations-- that are in well-restored monasteries.

Obviously, the Protestant Reformation in the early 1500s

and the religious slaughter dryly known as the Thirty Years War (1618-48)

changed the Roman Catholic monastic tradition that had flourished in

Europe since its beginnings under St. Benedict at Monte Cassino in the

sixth century. In the 1500s and 1600s thousands of Catholic churches

and monasteries were destroyed, put out of business, or converted to

Protestantism in England and Central Europe. Those events, however,

left the heartland of the Roman Catholic faith, Italy, largely untouched.

The Vatican States were left intact and the vast Kingdom of Naples,

half of the Italian peninsula, survived the religious strife that

had wracked northern Europe. Thus, in the city of Naples in the year

1700, out of a total population of 300,000, fully one-tenth of that

number --one out of every ten Neapolitans!-- was either a priest, a

monk, or a nun living and working in the churches and adjacent monasteries

of Naples. Obviously, the Protestant Reformation in the early 1500s

and the religious slaughter dryly known as the Thirty Years War (1618-48)

changed the Roman Catholic monastic tradition that had flourished in

Europe since its beginnings under St. Benedict at Monte Cassino in the

sixth century. In the 1500s and 1600s thousands of Catholic churches

and monasteries were destroyed, put out of business, or converted to

Protestantism in England and Central Europe. Those events, however,

left the heartland of the Roman Catholic faith, Italy, largely untouched.

The Vatican States were left intact and the vast Kingdom of Naples,

half of the Italian peninsula, survived the religious strife that

had wracked northern Europe. Thus, in the city of Naples in the year

1700, out of a total population of 300,000, fully one-tenth of that

number --one out of every ten Neapolitans!-- was either a priest, a

monk, or a nun living and working in the churches and adjacent monasteries

of Naples.

That did

not change significantly until the French took over the Kingdom in 1806.

The anti-clericalism of the French Revolution closed most of monasteries

in parts of Europe that were under French control between 1795 and 1814;

that included the monasteries in Naples, which were closed by Murat's

decree of 1812. Monasteries in Naples never recovered from that, even

after the restoration of the old social order by the Congress of Vienna

in 1815. Later, the second great "suppression" of monasteries in Italy

occurred in 1864, after the unification of Italy. Thus, in Naples, though

there are still some true working monasteries left, such as Santa

Chiara, San Gregorio Armeno, and Camaldoli,

most of the grand old monasteries now serve other purposes, and it is

interesting to look at a few of these.

The City

Hall of Naples is the ex-monastery of the adjacent church of San Giacomo

(St. James) degli Spagnoli. It was built in the mid-1500s and was vast.

An inner passage connected the front of the complex to via Toledo, the

main road running behind it. That passage was closed as a result of

the construction of the new Bank of Naples in 1939. (The City Hall is

seen at left-center, at the top of the square, in the photo of Piazza Municipio.) One of the two structures on the

hill above Naples is another ex-monastery, the Museum

of San Martino. The photo at the top of this entry shows the courtyard

of the monastery of S. Maria La Nova. Administrative offices for the

city now occupy the premises. The church, itself, is still a church

and is the object of a separate entry.

Various

departments of the University of Naples

have taken over a number of former religious facilities. The Medical

School sits on the height at the old northwest corner of the city, approximately

overlooking today's Archaeological Museum and Piazza Cavour. That university

department has incorporated a number of smaller churches and cloisters

that themselves were on the sites of ancient Greek buildings. Also,

the recently restored Cloister of Saints Marcellino and Festo now houses

the Paleontology Department (click here).

The university library, itself, is behind the modern university building

and is on the premises of the old Chiostro (Cloister) del

Salvatore, an immense structure built in the 1570s that runs all

the way up the hill behind the university almost to Piazza

San Domenico Maggiore. It is still a tourist attraction because

of its so-called "courtyard of statues", a display of busts of illustrious

persons such as Bruno, Vico, and Aquinas.

The Architecture Department of the University of Naples

is currently (2002) in the process of expanding to the premises of the

old monastery of the Church of the Spirito Santo (photo, left).

The entire complex was, indeed, vast. It was built in the mid-1500s

and the historical marker near the entrance (photo insert) on via Toledo

marks it as a "Conservatory" for the poor, reminding us of the original

meaning of that word --a place to help the poor-- and, in many cases,

"conserve" orphaned and abandoned children. (The extended meaning of

"music school" is, apparently, a Neapolitan coinage. (Click on the 'Music

Conservatory' link, below.) The Architecture Department of the University of Naples

is currently (2002) in the process of expanding to the premises of the

old monastery of the Church of the Spirito Santo (photo, left).

The entire complex was, indeed, vast. It was built in the mid-1500s

and the historical marker near the entrance (photo insert) on via Toledo

marks it as a "Conservatory" for the poor, reminding us of the original

meaning of that word --a place to help the poor-- and, in many cases,

"conserve" orphaned and abandoned children. (The extended meaning of

"music school" is, apparently, a Neapolitan coinage. (Click on the 'Music

Conservatory' link, below.)

The massive building that now houses the State Archives

was originally the Benedictine monastery of Saints Severino and Sossio

(photo, right) and is in the heart of the old city, near the intersection

of Via S. Biagio dei Librai ("Spaccanapoli") and Via Duomo. The

monastery was one of the largest in the city and also one of the oldest,

dating back to the 10th century. It was also known as the "cloister

of the plane tree" as legend has it that the original building was erected

in a grove of trees of that species (platanus), a specimen of

which had been given to St. Benedict, himself. The history of the

first few centuries of the monastery remains obscure; true enlargement

of the premises started in the 1400s. Within the modern building are

to be found works of art depicting the history of the Benedictine order. Also,

the Music Conservatory, the Military barracks at Monteoliveto, the School

for Architectural Restoration, and the Monastery

of Piedigrotta are other examples of religious institutions converted

to other use, mostly in the last 100 years. The list is, indeed, long.

Perhaps we do well to look at the gradual conversion of monasteries

to other uses not so much as the result of forced closures, although

that, too, did happen. It is also a sign of the changing times. "Personal"

monasticism --that is, individuals going on religious retreats once

in a while to get away from it all-- has become somewhat fashionable

recently, but there is no doubt that large, full-time monastic orders

are an anachronism, witness the long decline in those willing to

enter upon religious callings such as the priesthood. The massive building that now houses the State Archives

was originally the Benedictine monastery of Saints Severino and Sossio

(photo, right) and is in the heart of the old city, near the intersection

of Via S. Biagio dei Librai ("Spaccanapoli") and Via Duomo. The

monastery was one of the largest in the city and also one of the oldest,

dating back to the 10th century. It was also known as the "cloister

of the plane tree" as legend has it that the original building was erected

in a grove of trees of that species (platanus), a specimen of

which had been given to St. Benedict, himself. The history of the

first few centuries of the monastery remains obscure; true enlargement

of the premises started in the 1400s. Within the modern building are

to be found works of art depicting the history of the Benedictine order. Also,

the Music Conservatory, the Military barracks at Monteoliveto, the School

for Architectural Restoration, and the Monastery

of Piedigrotta are other examples of religious institutions converted

to other use, mostly in the last 100 years. The list is, indeed, long.

Perhaps we do well to look at the gradual conversion of monasteries

to other uses not so much as the result of forced closures, although

that, too, did happen. It is also a sign of the changing times. "Personal"

monasticism --that is, individuals going on religious retreats once

in a while to get away from it all-- has become somewhat fashionable

recently, but there is no doubt that large, full-time monastic orders

are an anachronism, witness the long decline in those willing to

enter upon religious callings such as the priesthood.

Very practical

matters, as well, play a part --modern urbanization-- for example. Some

of the monasteries built in the 1500s in Naples were, at the time, on

the outskirts of the city. The Church of the Spirito Santo, mentioned

above, was outside the city wall and at the foot of a bucholic hillside.

Today, it is in downtown Naples. Even more dramatic is an institution

such as the Cloister of Suor Orsola, a convent built in the mid-1600s

halfway up the hill to San Martino at the top. When Suor Orsola was

built, there was scarcely a trail, much less a road on the hillside.

It was in the country. That section of Naples was opened to urbanization

by the construction in the mid-1800s of what has become one of the main

thoroughfares of the city, Corso Vittorio Emanuele. Since 1901, the

old convent has functioned as a women's college.

Bank

robbers, Latin

I

hope this one is true. The paper reports that two Neapolitan bank robbers

trying to pull a heist way up north in Modena were foiled by their inability

to speak standard Italian. They explained to the teller that they had

box cutters in their pockets and were going to start slicing and dicing

if they didn't get lots of those brand new Euros --all of this in a

Neapolitan dialect about as intelligible to a bank teller in Modena

as Middle High Kurdish. After 3 or 4 more attempts, each one eliciting

from the teller responses like "I'm sorry. I don't understand you" or

"Do you want to open an account here, sir?" or "Has our automatic teller

machine outside gobbled up your credit card? Sorry. Let me call the

manager...", the speechless bad-guys fled lootless in their stolen car,

later recovered. One witness reports that on the way out of the bank,

the second thief called his spokescrook companion an idiot for not being

able to ask for money in real Italian. (See

here for an item on the Neapolitan language.) I

hope this one is true. The paper reports that two Neapolitan bank robbers

trying to pull a heist way up north in Modena were foiled by their inability

to speak standard Italian. They explained to the teller that they had

box cutters in their pockets and were going to start slicing and dicing

if they didn't get lots of those brand new Euros --all of this in a

Neapolitan dialect about as intelligible to a bank teller in Modena

as Middle High Kurdish. After 3 or 4 more attempts, each one eliciting

from the teller responses like "I'm sorry. I don't understand you" or

"Do you want to open an account here, sir?" or "Has our automatic teller

machine outside gobbled up your credit card? Sorry. Let me call the

manager...", the speechless bad-guys fled lootless in their stolen car,

later recovered. One witness reports that on the way out of the bank,

the second thief called his spokescrook companion an idiot for not being

able to ask for money in real Italian. (See

here for an item on the Neapolitan language.)

That brings

to mind a story about the great Senegalese scholar and poet, Léopold

Sédar Senghor, President of his nation from 1960-80. During his

term of office, he had occasion to pay a state visit to Italy. Unsure

of his Italian, the super-erudite Senghor addressed the Italian senate

in Latin! He was disappointed when he found out that these neo-Romans

no longer possessed even rudimentary comprehension of the language of

their forebears. The Italian press was mortified.

I was never

much of a Latin scholar at school. I did, however, study a neo-Latin

language called Spanish, but by the time the Spanish got around to the

language there were no more ablatives, datives or passive participles.

That stuff had all been replaced by bull-fights, red wine and Flamenco

babes with roses between their teeth. My kind of language.

Later,

many years out of school, I did discover an interest in Latin, however,

when I came across my first Asterix comic book. Asterix is a Celt warrior

who wages funny war against the Roman oppressors in Gaul. Depending

on where you buy your comics, Asterix speaks German or French or English,

etc. Some enterprising scholar decided to do it up right, because the

version I picked up was in Latin. I couldn't read it, of course, but

I was intrigued. Then, when I found my first Donald Duck comic in Latin,

I became aware of the growing conspiracy to resurrect what to many is

a useless language.

Useless?

Well, in many European universities as late as the 18th century, Latin

was still the language of instruction, and it was the lingua franca

of the Roman Catholic church for a long, long time. Even today, the

Vatican still generates significant numbers of documents in Latin, and,

thus, keeps scholars at work updating the language in order to be able

to deal with concepts Caesar never had to worry about. (At a recent

Vatican congress dealing with the problems of keeping the language alive,

at least as an ecclesiastical medium, reporters from RAI, the Italian

State television network, were forced to ask their questions and get

their answers in Latin. The interview was subtitled in Italian at the

bottom of the screen.) An 18,000 word dictionary of recent coinages

has recently been published by the Vatican. Some of the entries:

fax: exemplum

simillime expressum

bestseller: liber maxime divenditus

gulag: campus captivis custodiensis

car wash: autocinetorum lavatrix

pinball machine: sphaeriludium electricum nomismate actum

The internet

has a number of sites dedicated to the revival of Latin, and one local

Neapolitan I know of --who has made said revival his labor of love--

comes to the phone with "ego sum".

Food

I

see that the First International Pasta Exhibition is opening tomorrow

down at the gigantic passenger terminal of the Port of Naples. Typically,

they will spend a lot of time talking about eating and not enough time

actually handing out free samples. I fully expect panels of self-important

sociologists to hold forth on "Societal Incorporation of Emerging Syntheses

in Higher Order Gastronomic Structures". [Also, see here] I

see that the First International Pasta Exhibition is opening tomorrow

down at the gigantic passenger terminal of the Port of Naples. Typically,

they will spend a lot of time talking about eating and not enough time

actually handing out free samples. I fully expect panels of self-important

sociologists to hold forth on "Societal Incorporation of Emerging Syntheses

in Higher Order Gastronomic Structures". [Also, see here]

No doubt

there will be some justifiable complaints about "fast food". MacDonald's

are all over and --food philistine that I am-- I have eaten there. The

main one is in the university district and is actually not a bad place

for students to sit and read. No one hassles them if they nurse a soft-drink

for an hour or so. I am reminded of at least the title of Hemingway's

short-story, A Clean Well-Lighted Place. Everyone needs a place

to sit sometimes.

There is

a local anti-fast-food society with the English name "Slow Food". They

send out invitations to their monthly affairs. You show up and spend

a half-hour or so warming up by admiring the vittles -- the texture

of this noodle or aroma of that artichoke. Ah, maccheroni 97

! --an excellent year-- with an aggressive but not presumptuous

bouquet we think will amuse you.

Halloween

Halloween

decorations have already sprouted in shop windows in parts of Naples.

This is much too early, especially for a place that doesn't celebrate

Halloween. Witches, goblins, Walpurgisnacht, and Night on Bald Mountain

--none of that is really part of southern Italian mythology unless you

head over to the area near Benevento, where, indeed, they celebrate

the tregenda magica-- the Witches' Sabbath, a throwback to the

long presence in that area of the Lombards, a Germanic people. (Click here to read an article with more information

on the Lombards.) Halloween

decorations have already sprouted in shop windows in parts of Naples.

This is much too early, especially for a place that doesn't celebrate

Halloween. Witches, goblins, Walpurgisnacht, and Night on Bald Mountain

--none of that is really part of southern Italian mythology unless you

head over to the area near Benevento, where, indeed, they celebrate

the tregenda magica-- the Witches' Sabbath, a throwback to the

long presence in that area of the Lombards, a Germanic people. (Click here to read an article with more information

on the Lombards.)

Halloween

in Naples is simply more globalization -- this one of holidays. Northern

European and American Christmas icons, for example --Santa Claus and

Christmas trees-- are common here only since the end of W2. My mother-in-law

was living in northern Italy in WW2, where she had young German soldiers

quartered in her house. She was amazed a few days before Christmas to

see them setting up a small fir tree in her living room.

"Get that

tree out of my house!" she yelled.

"But, mamma," they said (even --or, maybe, especially-- young

German soldiers needed a mother figure), "it's Christmas!"

That didn't

make much sense to her. A tree? -- she had never heard of such

a thing before. She was from Naples and was used to the Neapolitan presepe as a symbol of the Yuletide. She

threatened to stop cooking for them and let her daughter (my wife's

sister) take over the kitchen. "Ach, nein!" was pretty much how

the Wehrmacht felt about that possibility. In retrospect, that single

act, alone, might have shortened the war by a number of months, but,

alas, a cultural rapprochement was reached. The tree stayed, and she

kept cooking.

The Bourbons (1)

In the early 1700s the Kingdom of Naples came out of the War of the

Spanish Succession in the hands of the Hapsburgs, the royal house of

Austria. Then, the Austrians were driven from Naples by a young

prince from the Spanish branch of the House of Bourbon, to be known

upon his accession to the throne of Naples in 1734 as Charles III (painting,

left).

Naples

was an independent kingdom again for the first time in two hundred years.

After twenty-five years of rule, Charles would abdicate and return to

Spain. They say that before he left he was careful to return the crown

jewels. He even gave back a ring which he, himself, had found while

digging around Pompei, saying, "Even this ring belongs to the state".

This story, true or not, shows the regard, even veneration, that

has attached itself to this first Bourbon king of Naples. He was

paradoxically sad yet energetic, outgoing but melancholy, and he is

almost unanimously regarded as an example of the "enlightened monarch".

Charles

left impressive accomplishments: he restored some order to public finance,

curtailed church privilege, and built many now familiar, spectacular

architectural features, such as the royal palaces at Capodimonte, Portici

and Caserta. He also started the National Library, the Archaeological

Museum, a National Academy of Art and the excavations at Pompei and

Herculaneum. By the middle of the century, Naples was a capital of Enlightenment

Europe, and Antonio Genovesi, lecturing at the University, could

freely speak of redistribution of property and agrarian reform. Also,

Naples developed into a music capital of Europe, much of it performed

in the most splendid theater of its day, San Carlo.

Most of

all, perhaps, Charles encouraged the growth of a new commercial middle-class

and sought to move his subjects out of the lingering middle ages of

anachronistic class privilege and baronial abuse. Well-meaning or not,

however, he was not entirely successful in confronting this age-old

problem, which is evidence of the powerful inertia of centuries of feudalism

and of the overwhelming forces of reaction arrayed against him. In 1759

Charles returned to Spain to succeed his father on the Spanish throne.

He left Naples in the hands of his eight-year old son and a regent.

His son

Ferdinand ruled until 1825. It was to be a dynamic period: the Industrial

Revolution, the social and political theories of Rousseau and the music

of Ludwig van Beethoven. Primarily, it was the French Revolution, Napoleon,

and armies ranging over Europe on an unprecedented scale. If, from the

late 20th century, we look back at, say, the 1750's and view as 'quaint'

a scene of fat bewigged monarchs bouncing on horseback through the woods,

by 1825 the scene would change: a young Darwin would be wondering what

made the world go round and Karl Marx would already be seven years old.

It would be many things, but not 'quaint'.

Back to 1759. Ferdinand (paintings, left) was uniquely unfit to run

a kingdom. He was a good-natured knucklehead who spoke only the local

dialect, loved to roughhouse and bandy jokes with his servant and, indeed,

felt so at home among them that he was called the "lazzarone"

king, that term (apparently from St. Lazarus, the patron saint of lepers)

being the term for any of the unwashed teeming masses. He hated to read,

but was very big on the other two Rs —riding and relaxing. Fortunately,

Charles III had left the Foreign Secretary in charge, one marquis Bernardo

Tanucci, a capable and intelligent manager. Even after the child-king

came of age in 1767, Tanucci ran the government down to the minutest

detail. He was basically concerned with conserving the cultural and

economic institutions which Charles had left in place, and he did as

good a job as possible in the face of a baronial and ecclesiastical

opposition determined to preserve its privileges.

In 1768

Ferdinand married the Archduchess Maria Carolina of Austria (painting,

below) the sister of the Emperor and the younger sister of Marie Antoinette.

She was intelligent, headstrong and utterly convinced that she had been

born to rule. She had a seat on the ruling council of Naples and set

about to make Naples into what a royal court should be, another Vienna

or Paris. She owned and treated the king like the fun-loving sheepdog

he was and during the 1770s and 1780s made Naples into less of

a marketplace of Enlightenment thought and more of a showcase of royal

glitter with cultural institutions nevertheless still worthy enough

to attract Mozart and Goethe.

The queen forced Tanucci to resign, and she acquired

the services of John Acton, an ex-patriate

Englishman who had been commander of the naval forces of Tuscany. In

the decade before the French Revolution, Acton remade the Neapolitan

royal navy into one of the finest fleets in the Mediterranean. He opened

arms and ironworks factories, built bridges and roads and founded the

Royal Military Academy. By the time of the Revolution (1789),

he, as much as the queen, was in charge of the Kingdom of Naples. The

king was usually out hunting. The queen forced Tanucci to resign, and she acquired

the services of John Acton, an ex-patriate

Englishman who had been commander of the naval forces of Tuscany. In

the decade before the French Revolution, Acton remade the Neapolitan

royal navy into one of the finest fleets in the Mediterranean. He opened

arms and ironworks factories, built bridges and roads and founded the

Royal Military Academy. By the time of the Revolution (1789),

he, as much as the queen, was in charge of the Kingdom of Naples. The

king was usually out hunting.

When the

French Revolution started, Acton and the Queen were concerned with keeping

the kingdom safe from infection by revolutionary French ideas. Interestingly,

the masses in Naples— those who might have stood the most to gain

from storming a Bastille or two—did not seem to be interested

in throwing off their yoke. Intellectuals debated the virtues

of revolution and radical social reform, but the people, themselves,

generally liked their king and disliked anything French, even progress.

By 1793,

however, the French King Louis XVI had been beheaded, the Austrians

and French were at war, and battles were flaring up in northern Italy

as revolutionary fervor took hold. Naples agreed with the rest of European

royal opinion that the revolution had to be stemmed, and in the summer

of 1793 troops from the kingdom joined the Spanish and British

at the port of Toulon, recently taken by the British, to keep it from

being recaptured by forces of the French Republic. They failed, and

in so doing gained the dubious distinction of providing a young

artillery officer from Corsica with his first victory—and a promotion

from lieutenant to Brigadier General. By 1797, Napoleon had swept through

northern Italy, and in 1798 the French invaded the Vatican States to

set up the Roman Republic. Through their looting and violent antireligious

behavior (including the imprisonment of the Pope), they alienated the

Roman populace completely. Naples then sent troops to drive the French

from Rome. They were unsuccessful and the French counterattacked into

the kingdom. With French troops at the door and the now very real threat

of Republican insurrection from within the city of Naples, the King

and Queen fled to Sicily on Christmas of 1798.

Naples

fell after bitter fighting between Republican French troops and their

Neapolitan sympathizers on one side and the ever loyal poor lazzaroni

on the other, dedicated to their king right to the end. With the

French victory, the Parthenopean Republic was declared. Although some

have termed it a 'revolution', there is little doubt that the Republic

was imposed by force from without. The French also imposed war 'reparations'

on the new Republic, thus further antagonizing the people.

The Republic was destined to last a mere five months. The King and Queen

may have fled to Sicily, but they were not idle.

King Ferdinand

set about retaking his kingdom. He found Cardinal Ruffo, a warrior zealot who landed on the

Calabrian mainland with nothing but a flag and his own forceful personality.

Ruffo raised an army from among the tough peasantry in the surrounding

countryside as he marched north.

Depending

on who is telling the story, Ruffo's Christian Army of the Holy Faith,

the sanfedisti, were either ruthless fanatics or they were a

collection of Robin Hoods (such as the famous bandit, Fra Diavolo) loyal to their king, on a mission to

drive out foreign invaders. In fairness to Ruffo, he tried to curb the

excesses of his troops, and if they were violent, it is equally true

that their opponents, those who were dispensing Republican libertè,

fratenitè et ègalitè in the ex-kingdom of Naples

at the moment, were generally the same sort who a few years earlier

during the Terror in Paris had lopped off 2,500 heads, most of which

were guilty of little else except holding wrong thoughts. Suffice it

to say that there was barbarism on both sides as Ruffo swept north,

up through Calabria and Puglia, into Campania and towards the capital.

The tide

was now turning swiftly against the French Republic in Europe. Combined

forces of the monarchies in Britain, Russia and Austria were taking

advantage of the absence of Napoleon. He was off in Egypt during most

of 1799 attempting, and ultimately failing, to destroy British influence

in the Mediterranean. During that time, virtually all of the Republic's

advances in northern Italy, which he had brilliantly forged two years

earlier, were reversed. For Naples, the time could not have been better

for a royalist reconquest. The French pulled the main body of their

army north and left a token force in the city. With British allies under

Admiral Nelson blockading the port of Naples, Ruffo and his army entered

the city. They offered the defenders free passage if they surrendered.

They did, but Nelson, certainly at the behest of the royal family, still

in Sicily, and over the strenuous objections of Ruffo, who had given

his Christian word, had a number of the Republican defenders put to

death, including the Republican Admiral, Caracciolo, who was hanged

from the yardarm. The subsequent mass trials and executions of supporters

of the Republic are infamous. (Read about one victim, Eleonora

Fonseca Pimentel.)

Royalist

Neapolitan forces had taken advantage of a general French collapse in

Northern Italy and, indeed, the collapse of the French Republic, itself.

For a moment in late 1799, after a decade of incredible turbulence,

the monarchies of Europe saw 'the light at the end of the tunnel'. It

was a brief respite, however, for Bonaparte was back in Paris and on

November 9, 1799, he overthrew the French Directory and became First

Consul. It was notice to the princes and kings of the continent not

to get too comfortable in the imperial mantle of Charlemagne.

[continued

at Bourbons (2).]

|