©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Krupp, Alfred; Capri (2)

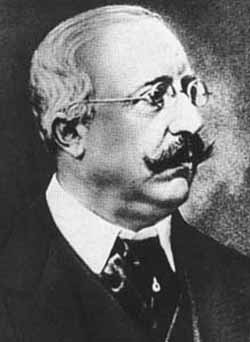

Friedrich

"Fritz" Alfred Krupp (1854-1902)—the "Cannon King" and bearer

of a name tenaciously associated with German industry and militarism—was

taken with Capri and is, in a sense, still present on the island in

the trail that bears his name, the Via Krupp, a spectacular footpath

leading down the sheer south side of the island to the sea. Friedrich

"Fritz" Alfred Krupp (1854-1902)—the "Cannon King" and bearer

of a name tenaciously associated with German industry and militarism—was

taken with Capri and is, in a sense, still present on the island in

the trail that bears his name, the Via Krupp, a spectacular footpath

leading down the sheer south side of the island to the sea.

Krupp made

his first visit to the island in 1898, on his doctor's orders. This

otherwise practical man became the incurable romantic on the island,

palling around with local fishermen and sitting in small taverns listening

to Neapolitan songs. He also indulged his amateur passion for marine

biology by assisting the great German naturalist (and founder of the

Naples Aquarium), Anton Dohrn, who was doing research in the Bay of

Naples.

Other than

marine biology, 'Fritz' devoted much of his time on Capri to a grotto

that had been the abode of a 16th century religious recluse, one Fra

Felice. Krupp turned the cave into a "pleasure palace," replete with

golden keys for the gates, keys that he gave to his close friends on

the island, young fishermen, waiters, etc. He referred to his

grotto as the "holy place of a secret fraternity," thus doing

little to allay rumours about the nature of the pleasure being pursued

by himself and his young male friends. Krupp built a path to the cave

and then offered to expand it to lead from the certosa

(a 15th-century monastery) down to the Marina Piccola, the small harbor. The project was accepted by the island authorities,

and it was this path that became the Via Krupp. It was finished by the

spring of 1902. A few months later, apparently driven to it by the scandals

surrounding his alleged perversions on Capri, Krupp, ruler of the giant

German industrial dynasty, this richest man in Germany, died by his

own hand.

(Fritz

left the world's most impressive munitions factory to Gustav von Bohlen-Halbach,

his daughter Bertha's husband. A few years later, Gustav built

the largest artillery piece in history to lob shells into Paris

from 50 miles away in WWI. That weapon was nicknamed "Big Bertha,"

which tells me more than I really want to know about life in the Bohlen-Halbach

household!)

As for

the Via Krupp, it is currently closed. It is not a recent problem.

It was a difficult path to build, and there have always been problems

with falling rock. Nevertheless, for over sixty years, it was

kept clear by the practical expedient of a man on the end of a

pulley going down the side of the cliff and knocking down dangerous

bits of the cliff face before they fell. Authorities, however,

decided that it was no longer worth the expense to keep the trail free,

and they closed it in 1978.

It is now

awaiting a decision on just how to make it safe. There have been a

number of plans. One called for covering the rock-face with the

same type of metal netting that one sees in similar terrain all over

the world (and on Capri, itself, on the cliff-face as you wind up the

road to Anacapri). Another involved the application of that 'natural-looking'

concrete spray (the kind that generally draws comments like, "Say, that

almost looks real, doesn't it?"). Finally, some wanted to build

a sheltered passageway, a tunnel, along at least parts of the trail,

to protect hikers from falling rock.

It is really

a two-fold problem. One involves the safety of the trail itself. That

is hard, but not that hard. They did it for decades. Two is somewhat

more intricate. It is the perception that the Via Krupp is somewhat

of a metaphor of not only the entire island, but of similar places

that depend on a tourist economy throughout the world. Paul Fussel's

term 'pseudo-place' comes to mind, a description of those formerly

small towns and villages that today have the sole function of luring

in tourists and selling them things. Many are worried that Capri has

become—or is becoming—just such a 'pseudo-place',

a process that will only be accelerated by applying concrete or

building sheltered passageways along the island's most famous path.

It's a

hard compromise to find. Certainly, one should not fall for the myth

that before the Isle of Capri was invaded by hordes of tourists, it

was some idyllic gem set in the sea, a paradise for inhabitants

and visitors alike. Our impression of Capri as the "Isle of Pleasure"

has been formed largely by foreigners who had enough money to enjoy

the island on their own terms, and who, it might be noted, were greatly

resented by the local population, farmers and fishermen whose harsh

lot improved only with the beginning of tourism on Capri at the turn

of the century. On the other hand, the Via Krupp has always been a strange

combination of nature and the hand of man, somewhat like Japanese Bonsai.

Maybe a bit a falling rock isn't such a bad idea.

Aquarium,

villa comunale (2)

Elia

Mannetta, the engineer from Baltimore who built the new aquarium in

Genoa, will be in Naples in a week or so to help decide if the city

of Naples needs a new aquarium and, if so, where to put it. There are

three candidates: (1) in San Giovanni a Teduccio, a suburb of Naples

just to the east along the coast; (2) Bagnoli, where a new aquarium

would fit in nicely with the pedagogical ambitions of the Science City

exposition and fair grounds as well as with a general rejuvenation of

the area after decades of decay; (3) in the Villa Comunale, where a

new aquarium would take the place of the older one, the Anton Dohrn

Aquarium, in place since the 1870s. Choice number 2, Bagnoli, is probably

the strongest candidate. Elia

Mannetta, the engineer from Baltimore who built the new aquarium in

Genoa, will be in Naples in a week or so to help decide if the city

of Naples needs a new aquarium and, if so, where to put it. There are

three candidates: (1) in San Giovanni a Teduccio, a suburb of Naples

just to the east along the coast; (2) Bagnoli, where a new aquarium

would fit in nicely with the pedagogical ambitions of the Science City

exposition and fair grounds as well as with a general rejuvenation of

the area after decades of decay; (3) in the Villa Comunale, where a

new aquarium would take the place of the older one, the Anton Dohrn

Aquarium, in place since the 1870s. Choice number 2, Bagnoli, is probably

the strongest candidate.

Very few

Neapolitans would like to see the Villa Comunale dug up and closed again

(as it was a few years ago for restoration) or see the current aquarium

demolished. It fits in with the general old-fashioned atmosphere of

the park—classical statues, fountains, gazebo/bandstands, etc.—though

that, too, has changed a bit since the recent overhaul. Not only did

they chop down a lot of trees ("Diseased," some said…"My brother–in–law

needs firewood," said others) but they replaced a number of 19th–century

metal scrolls and curlicues along the fence with more modern bulletoid

metalwork that has already midwifed an entire repertoire of suppository

jokes.

(For a

sepate entry on the Villa Comunale.)

Mercato,

Piazza (2); Carmine (church and square)

I am looking

for a word—"psychotactility"?— to describe that sensation

you get when you lay your hands on something ancient—part of a

Greek wall, say, in Naples, and close your eyes and suddenly feel that

you are in touch with the ancient Greeks. ("Ulysses? Is that you? Can

you hear me?" It's ok to talk during these episodes. The people near

you will just think you're using a hands–free cell–phone.)

That sensation doesn't happen to me very often. Well, all right—it

has never happened; I just thought it would be nice to have a word for

it.

One place

it really doesn't happen is in the middle of a squalid parking

lot that used to be one of the most important sites in the city. I tried

again today, and all I "felt" were the cars. ("Mr. Ford? Mr. Daimler?

Are you there? Curse you!") I am referring to Piazza Mercato—"Market

Square," the setting for a number of episodes of extreme interest in

the history of Medieval Europe.

The square

is at the easternmost point of the old medieval wall along the

coast (see this entry) where the Carmine

Castle used to stand. The historic old church, Santa Maria del Carmine

(also called Carmine Maggiore) is just off the square. It is still in

use and the75–meter belfry is still visible from a distance even

amidst newer and taller buildings.

For such

a noteworthy church, its pedigree is obscure. A document from 1589,

the Cronistoria del Convento, by one Padre Moscarella, says that

the church was founded in the 12th century by Carmelite monks driven

from the Holy Land during the Crusades, presumably arriving in the Bay

of Naples aboard Amalfitan ships. Other sources place the original refugees

from Mount Carmel as early as the eighth century. Whatever the case,

the fact remains that by 1268, the date of the execution in Piazza Mercato

of Conradin, the last Hohenstaufen pretender to the throne of the Kingdom

of Naples, at the hands of Charles I of Anjou, the church and adjacent

monastery were well established. The square, itself, had become the

largest market place in the city, having replaced in importance the

ancient market in the heart of the old city, itself.

With the

execution of Conradin, the square also became the place for official

executions and would remain so for many centuries. It was the site of

the grisly Bourbon executions of Republican

revolutionaries in 1799. It was for centuries a general gathering

place, watering hole and focal point for celebration as well as rebellion.

In 1647 the square was where trouble broke out between rebels and royalist

troops during Masaniello's Revolt and

a last-stand rallying point for Bourbon forces resisting Garibaldi's

move on Naples in 1860.

All of

that history was ploughed under during the great Risanamento—Urban Renewal—of Naples

around 1900. The new port road was put in, the old castle demolished,

part of the monastery, itself, torn down, etc. Whatever else the merits

of the Risanamento were, it shifted the center of the city well away

from the port and to the west. The new straight road through town, Corso

Umberto, divided the city in half. The port half—Piazza Mercato—decayed

terribly over the decades. It was also subjected to aerial bombardment

in WWII. The area is just now coming back to life—unfortunately

with the worst imaginable mishmash of architecture.

The Church

of the Carmine continues to thrive and serve the needs of the faithful

in the area. The old monastic premises adjacent to the church now serve

as a shelter for the needy and homeless. The church is home to two remarkable

religious relics: One, the painting of the "Brown Madonna," said to

have been brought by the original Carmelites; two, a figure of the Crucifixion

in which the crown of thorns is missing. Legend says that the crown

fell as Christ's head moved when the building was struck by a cannon

ball in 1439.

Yet, as

I said at the top of this entry, there is very little of all that still

hanging around in the air, if you will. The square is now a totally

anonymous and grimy parking lot.

Cars

(1)

There

really is no place to park a car in Naples anymore. Double-parking is

so common that traffic cops look the other way. They have a difficult

time drawing a firm line in the sand on this issue since most of the

beaches, too, are strewn with illegally parked cars. You may get a ticket

if you triple-park and swing open the driver-side door into passing

traffic, thereby causing some poor kid on a motor–bike to slam

into you and go flying over the door. ("But he wasn't wearing a helmet,"

you can always argue. And he probably wasn't.) Sometimes cars are towed,

but it seems to be random. There isn't as much bad feeling over towed

cars as one might think because if you come out of your house and find

your car gone, you naturally think that it's been stolen. That's an

ineluctable force of nature in Naples. No sense getting riled up over

that. There

really is no place to park a car in Naples anymore. Double-parking is

so common that traffic cops look the other way. They have a difficult

time drawing a firm line in the sand on this issue since most of the

beaches, too, are strewn with illegally parked cars. You may get a ticket

if you triple-park and swing open the driver-side door into passing

traffic, thereby causing some poor kid on a motor–bike to slam

into you and go flying over the door. ("But he wasn't wearing a helmet,"

you can always argue. And he probably wasn't.) Sometimes cars are towed,

but it seems to be random. There isn't as much bad feeling over towed

cars as one might think because if you come out of your house and find

your car gone, you naturally think that it's been stolen. That's an

ineluctable force of nature in Naples. No sense getting riled up over

that.

A gentleman

put "a modest proposal" in the paper the other day. A decade ago, the

city cleared out Piazza Plebiscito, the large square in front

of the Royal Palace in Naples. It has been returned to its natural,

wide–open, pristine state—spacious, clean, and eminently

walk-aroundable. The gentleman points out that "wide open spaces" are

all right for the Wild West and Asian steppes but we are human beings,

not buffalo, and such an area is not natural in the least wide-open

space in western Europe, Naples.

Let the

cars return, he argued. Bring those thousands of vehicles back from

the parallel, quantum Naples that they are star–gated to every

morning and let them park here in the real Piazza Plebiscito

where they belong. Certainly, nothing could be worse than the presence

of various works of "art" that take up space in the square a lot of

the time, from castles made of Coca–Cola cans to mountains of

salt to this year's display

of 100 bronze skulls. Why not—in keeping with "Art for the

masses" ambitions of the city—put on a permanent display of parked

cars as "mobile installation art"? Then, instead of slurping coffee

and holding maps of the city upside-down, visitors to our fair city

can put in some quality tourist time by admiring the kaleidoscopically

changing colors—Matisse, eat your heart out!—of the

square as cars putt about looking for spaces, or by deconstructing the

semiotics of the Hittite tridents, runes, alchemical emoticons and gypsy

logoglyphs that serve as hood ornaments.

Names

of kings

Astute

student of history that I am, I have figured out why monarchies have

not been doing too well, lately. It has nothing to do with sweeping

historical processes such as the Enlightenment or Hegelian Dialectics

or the guillotine. Quite simply, kings don't have really good nick-names

anymore—or 'bynames,' as they are properly termed. Astute

student of history that I am, I have figured out why monarchies have

not been doing too well, lately. It has nothing to do with sweeping

historical processes such as the Enlightenment or Hegelian Dialectics

or the guillotine. Quite simply, kings don't have really good nick-names

anymore—or 'bynames,' as they are properly termed.

In the

history of Naples, there is only monarch with a fine, regal by-name:

Alfonso the Magnanimous (1396-1458, photo), the one who wrested the

Kingdom of Naples from the Angevins in 1442. Other than that, Neapolitan

monarchs have been stuck with trifling nicknames. Ferdinand IV (later

Ferdinand I) (1751-1825) had two: Re Nasone and Re Lazzarone.

The first one means King Big Nose (Naso+ the augmentative suffix

–one). The second requires some explanation: Lazarus is

the patron saint of lepers, and, by extension, all miserable outcasts.

Neapolitan members of the "great unwashed peasant masses" were thus

called "lazzaroni". In an age of rigid social stratification,

it was not a derogatory term—it was a description. Ferdinand was

a notorious simpleton and vulgarian, and he enjoyed hanging around with

the common folk down at the port. He was popular, and both names were

terms of endearment bestowed on him by the Neapolitan masses. He was,

thus, the Great Unwashed Peasant King; it was an expression of solidarity

with the people, and he took no offense at that term or the one about

his nose.

His grandson,

Ferdinand II (1810-1859), was nicknamed "Bomba"—bomb—as

a result of his bombardment of Messina during the political unrest

in 1848. And his son, the last King of Naples, Francis II was known

as "Bombalino"—Little Bomb. All of these example were nicknames,

not by–names—not Someone THE Something.

There hasn't

been Anyone the Great in a long, long time: Alexander, Alfred, Peter,

Frederick, Katherine and, of course, Charles the Great (commonly known

by the Frenchified version, "Charlemagne"). Now that was a name fit

for royalty! I bet you could call them that, too. O, Great One!

Your Greatness! O, Generous Dispenser of Greatosity! or maybe,

simply, Oh, Great! They couldn't possibly have minded.

Or Leo

the Wise and Charles the Noble. Those were names! "Yes, Your Wiseness";

"You Bet, O Noble One!" —and in the case of our Neapolitan, Alfonso,

"Count on it, Your Magnanimosity!" Those old rulers knew that

21st–century history students would have attention spans roughly

equal to the reign of Harvey the Short Lived, and would not be remember

complex items like Vth or IIIrd or XXIst, so they tacked on little memory

boosters.

Charlemagne's

grandfather wasn't taking any chances on not being remembered. He was

called Charles Martel —Charles The Hammer! Imagine that! The Hammer!

When they were choosing Dark Age kings in the eighth century, they went

right around the group:

"OK, which

one of you guys wants to be king? Robert IV?…Got any experience,

Bob? Junior League jousting coach, huh? Let's see …"

Then suddenly

from the gloom in the back of the tent comes that rich Dark Age baritone

of command:

"They call

me 'The Hammer'!"

Forget

'Will you open the envelope, please.' End of discussion, right there.

I'm not so sure you could actually call him that, though. I mean, do

you really want to pal around with someone called The Hammer? What happens

if this guy has some Thor-like flashback and starts flailing about in

a fit of Royal Peevishness? You get one tankard too many of the Good

Grape into someone called The Hammer and you can put some serious dents

in Ye Olde Royal Happie Hour, and that's the sooth. His son was Pepin

the Short! O, Great One! —definitely. Your Wisehood!—yes.

And maybe even, under specially contrived circumstances, O, Most Hammering

One! But, Hey, Shorty!—I don't know.

A bit on

either side of the year 1000 we have Charles the Bald, Charles the Fat,

Charles the Simple and Charles the Pious. I recall that two of those

terms refer to the same person; thus, one of them was either The Bald

& Fat, The Fat & Pious, The Pious & Simple, The …let's

see… carry the 2 … well, you can work out the rest.

And what

can you say about Louis the Child? If I am intercalating all the leap

years in my Dark Age calendar correctly, this guy was an adult whom

they called "The Child". Go figure. "Is'm widdle queenie's gweat big

kingie-boo? Yes'm is!" On that note, maybe we'd have to ask Mrs.

Ethelred the Unready about the real story behind her husband's name.

Pietrarsa

(railway museum); Trains (2)

Unfortunately, one of the

most interesting museums in Naples is still closed for extensive repairs.The

Railway Museum of Pietrarsa is one of the most complete in the world.

It is located on the premises of the former metal foundry of the Kingdom

of Naples, a facility that produced most of the boilers for locomotives

and steam-driven ships in the kingdom in the first half of the 19th century. Unfortunately, one of the

most interesting museums in Naples is still closed for extensive repairs.The

Railway Museum of Pietrarsa is one of the most complete in the world.

It is located on the premises of the former metal foundry of the Kingdom

of Naples, a facility that produced most of the boilers for locomotives

and steam-driven ships in the kingdom in the first half of the 19th century.

The museum

contains original engines as well as scale models incorporated into

a display of the history of trains in Italy. The displays include the

Bayard, the first locomotive in Italy. It started its run from Naples

to Portici on October 3, 1838. With the unification of Italy, the construction

of steam boilers was taken over by industry in the North and Pietrarsa

was relegated to the role of a repair facility. It served in that capacity

until the 1970s when the facility was rendered obsolete by advances

in diesel and electrical technology. It opened as a museum in 1989.

Conservatory,

Music (1); San Pietro a Maiella

I got a note from a woman in France the other day asking

me if she could use my snapshot of the statue of Beethoven located on

the premises of the Naples Music Conservatory. That gave me an excuse

to wander down to that part of the city and have another look at the

place. The conservatory is right near Piazza

Bellini and a long street, via San Sebastiano, known simply

as the "music street" because every shop on it sells musical instruments.

It's always a pleasure to walk by the conservatory and listen to the

sounds of students practicing. The statue of Beethoven, indeed, broods

prominently in the courtyard of the conservatory. I had the opportunity

to take another photograph for the young woman and to learn that the

statue is the work of the prominent Calabrian sculpture, Francesco

Jerace. I got a note from a woman in France the other day asking

me if she could use my snapshot of the statue of Beethoven located on

the premises of the Naples Music Conservatory. That gave me an excuse

to wander down to that part of the city and have another look at the

place. The conservatory is right near Piazza

Bellini and a long street, via San Sebastiano, known simply

as the "music street" because every shop on it sells musical instruments.

It's always a pleasure to walk by the conservatory and listen to the

sounds of students practicing. The statue of Beethoven, indeed, broods

prominently in the courtyard of the conservatory. I had the opportunity

to take another photograph for the young woman and to learn that the

statue is the work of the prominent Calabrian sculpture, Francesco

Jerace.

Popular

Neapolitan etymology suggests that Naples is where the term conservatorio

was first used to mean 'music school'. Originally, however, a

conservatorio was where they conserved young, unmarried women

with children as well as orphans; thus, a 'conservatory' was a shelter

or orphanage. There were so many orphans being trained in music in these

church-run orphanages that the transfer of meaning came about rather

naturally over time.

These music

conservatories in Naples go back to the mid-1500s when the Spanish rulers

set up schools to train young singers on the premises of four monasteries

in the city: Santa Maria di Lorento, Pietà dei Turchini, Sant'Onofrio

a Capuana, and I Poveri di Gesù Cristo. They enjoyed a considerable

reputation as training grounds not only for young children to

be trained in church music, but, eventually, as a 'feeder system' into

the world of commercial music once that opened up in the early

1600s.

In 1806, with Napoleon Bonaparte's brother,

Joseph, installed as the king of Naples in what would be a

decade of French rule of the kingdom, monastic life in the kingdom

was drastically reorganized and the four monastery music schools were

consolidated into a single building, the Church of San Sebastiano.

In 1826 that consolidated conservatory was moved to the present

site, the ex-monastery, San Pietro a Maiella). The conservatory (still

bearing the inscription 'Royal Academy of Music' over the entrance)

is still an important music school in Italy. It houses an impressive

library of manuscripts pertaining to the lives and musical production

of composers who lived and worked

in Naples, among whom are A. Scarlatti, Pergolesi,

Cimarosa, Rossini,

Bellini, and Donizetti.

The historical museum has a display of rare antique musical instruments. In 1806, with Napoleon Bonaparte's brother,

Joseph, installed as the king of Naples in what would be a

decade of French rule of the kingdom, monastic life in the kingdom

was drastically reorganized and the four monastery music schools were

consolidated into a single building, the Church of San Sebastiano.

In 1826 that consolidated conservatory was moved to the present

site, the ex-monastery, San Pietro a Maiella). The conservatory (still

bearing the inscription 'Royal Academy of Music' over the entrance)

is still an important music school in Italy. It houses an impressive

library of manuscripts pertaining to the lives and musical production

of composers who lived and worked

in Naples, among whom are A. Scarlatti, Pergolesi,

Cimarosa, Rossini,

Bellini, and Donizetti.

The historical museum has a display of rare antique musical instruments.

The conservatory

and adjacent church (photo, above) are both part of the old San Pietro

a Maiella monastery complex, built at the end of the 13th century and

dedicated to the monk Pietro da Morone, who became Pope Celestine V

in 1294. Celestine subsequently became the only Pope to abdicate, an

event that also took place in Naples, in the Maschio Angioino, the Angevin Fortress. At least

in Dante's version of the afterlife, Celestine resides in Hell. The

Divine Comedy places him just past the gates of Hell among the

Opportunists --(in John Ciardi's translation)-- "...the nearly soulless

whose lives concluded neither blame nor praise...[and in reference

to Celestine]...I recognized the shadow of that soul who, in his

cowardice, made the Grand Denial...". (To play the Pope's

advocate, I remind you that Dante was really upset at the fact

the Celestine, by quitting, left the door open to the subsequent Pope,

Boniface VIII, corrupt and, in Dante's view, responsible for much of

the evils that befell Dante's city of Florence.)

| This

interesting mosaic is found as part of the floor tiling within the

church. |

The

building is a square Gothic-style church; after a fire in 1407 it was

restored and enlarged by the addition of two chapels and the relocation

of the facade. The number of interesting art works within include a

chapel by an anonymous artisan that tell the story of Saint Martin,

and the numerous frescoes above the choir. The marble altar is

from 1645 and is by Cosimo Fanzago. The church was redone in Baroque

style, as evidenced by the paintings of Mattia Preti inserted into the

ceiling of the central nave. They depict the Story of the life of San

Celestino and Santa Caterina of Alexandria and were done in 1657-59.

The church is on a street of the same name near Port’Alba, within

the bounds of the old Greek city. The

building is a square Gothic-style church; after a fire in 1407 it was

restored and enlarged by the addition of two chapels and the relocation

of the facade. The number of interesting art works within include a

chapel by an anonymous artisan that tell the story of Saint Martin,

and the numerous frescoes above the choir. The marble altar is

from 1645 and is by Cosimo Fanzago. The church was redone in Baroque

style, as evidenced by the paintings of Mattia Preti inserted into the

ceiling of the central nave. They depict the Story of the life of San

Celestino and Santa Caterina of Alexandria and were done in 1657-59.

The church is on a street of the same name near Port’Alba, within

the bounds of the old Greek city.

The life

of the conservatory has always been bound up with that of another great

musical establishment in the city of Naples, San Carlo Theater. (Click here to read about San Carlo.)

Horse's

head

I

am always amazed to find something original in better condition than

the copy. I thought that was why they made copies—because the

originals were in such terrible danger of deteriorating. That is why

I set out to find the building in Naples called, popularly, ‘the

house of the horse’s head’. I

am always amazed to find something original in better condition than

the copy. I thought that was why they made copies—because the

originals were in such terrible danger of deteriorating. That is why

I set out to find the building in Naples called, popularly, ‘the

house of the horse’s head’.

Technically,

the name is Palazzo Santangelo (also known as Palazzo Diomede

Carafa) named for the representative of the Aragonese court who

erected this building in the middle of the 15th century. It incorporates

part of an earlier structure from the 1200s. It is one of the most interesting

Renaissance buildings in Naples, containing elements of Florentine and

Catalan architecture. The rectangular stone facade, marble portals and

wooden door are all original. Worn by time, but still visible, are twelve

niches depicting members of the Carafa lineage. The ‘Santangelo’

name of the building goes back to the person who bought the building

in 1813 and restored it, as well as making it a repository for works

of fine art, many of which, unfortunately, have gone missing over

the years. It is on via San Biagio dei Librai, also known as "Spaccanapoli".

It is the bottommost of the three parallel east-west streets that make

up the historic center of Naples, those streets that are laid over the

old Greek and Roman roads. The building is a block east of the large

square named Piazza San Domenico Maggiore. (See #22 on the map

of the historic center.)

I had heard

that there was a copy in the courtyard of a bronze horse’s head,

a gift to Carafa from Lorenzo the Magnificent. Much popular superstition

has formed around the statue over the years: for example, merely bringing

sick animals into the presence of the statue was said to work miraculous

cures! Naturally, the original statue would be lost, destroyed,

ravaged by time or otherwise not at my disposal, so I had to find the

copy.

This

"Hercules," a copy of the famous original in the

National Museum next door, is in the same train station.

In my

heart of hearts, I think I was hoping to find peasants bringing their

sick goats and sheep to be healed. Alas, the building was an absolute

mess. It was in the agonizing process of being restored. There was scaffolding

on every wall in the courtyard; bricks were strewn about; and everything

was covered with fine powder blown off the piles of plaster and cement.

General construction debris was everywhere. But the horse was there.

The head was mounted on the back wall of the courtyard at about eye-level,

but it was barely visible beneath a rickety framework of pipe-and-wood

scaffolding; there was an overturned wheelbarrow in a pile of stucco

nearby. The statue was covered in grime and had become totally non-descript. In my

heart of hearts, I think I was hoping to find peasants bringing their

sick goats and sheep to be healed. Alas, the building was an absolute

mess. It was in the agonizing process of being restored. There was scaffolding

on every wall in the courtyard; bricks were strewn about; and everything

was covered with fine powder blown off the piles of plaster and cement.

General construction debris was everywhere. But the horse was there.

The head was mounted on the back wall of the courtyard at about eye-level,

but it was barely visible beneath a rickety framework of pipe-and-wood

scaffolding; there was an overturned wheelbarrow in a pile of stucco

nearby. The statue was covered in grime and had become totally non-descript.

I expressed

my disappointment to a gentleman standing nearby. I wondered when all

the work would be done. Hard to say. Probably a long time. Why didn't

I go see the original? The original? Sure. Up at the National Archaeological

Museum. It's on display, you know. I didn't.

Indeed.

I found the real horse's head, but not exactly where the gentleman said

it would be. The city—ever onward in its campaign to bring art

to the people—has moved this original gift from Lorenzo the Magnificent

next door to the new Museum stop of the Metro line—a train

station. Thus, as you trot down the stairs to get your train, you look

up over the entrance and there it is, encased behind protective plastic.

It is truly splendid and I shall return. I have a goat that is not feeling

too well.

Donn'Anna,

Villa

There

is much confusing, popular lore about this dreary building, located

on Via Posillipo as you start up that road from the Mergellina boat

harbor. It is called "Villa Donn'Anna" and if you ask residents of the

area, everyone is quick to tell you some variation of the theme that

this is where Queen Giovanna had sex orgies and murdered her lovers.

No one seems to be certain whether the Queen in question is Giovanna

(1326-1382), daughter of Charles, Duke of Calabria, or another Giovanna,

sister of King Ladislao. The first one had her husband murdered and

was accused of other foul deeds, as well. She looks like a good

candidate to be the evil queen, at least in the opinion of Italy's greatest

historian/philosopher of the 20th century, Benedetto Croce. There

is much confusing, popular lore about this dreary building, located

on Via Posillipo as you start up that road from the Mergellina boat

harbor. It is called "Villa Donn'Anna" and if you ask residents of the

area, everyone is quick to tell you some variation of the theme that

this is where Queen Giovanna had sex orgies and murdered her lovers.

No one seems to be certain whether the Queen in question is Giovanna

(1326-1382), daughter of Charles, Duke of Calabria, or another Giovanna,

sister of King Ladislao. The first one had her husband murdered and

was accused of other foul deeds, as well. She looks like a good

candidate to be the evil queen, at least in the opinion of Italy's greatest

historian/philosopher of the 20th century, Benedetto Croce.

To make

matters even more confusing, one Dragonetto Bonifacio is said to have

built the villa in the early 1400s, but there were apparently two persons

by that name at the same time in Naples!

The building

is on the site of the so-called "Rocks of the Siren" and, indeed, was

originally called "La Villa Sirena". It changed hands a number of tims

and finally was inherited in 1630 by the woman whose name it now bears,

Anna Stigilano, who then married the Spanish viceroy of Naples. She

had the building redone by the great architect, Cosimo Fanzago, in the

1640s and, since that time, the building has been called Villa Donn'Anna.

San

Bartolomeo

If you wander into the small maze of streets between

via Medina and via Depretis just west of Piazza Municipio, you will

find via San Bartolomeo. On this street is a tiny church —now

closed— called Santa Maria della Graziella. The church is on the

site of the original opera house of Naples and was opened as the San

Bartolomeo Theater in 1621. It, thus, got in on the beginnings

of opera, begun a few years earlier in Florence and turned into a full-blown

commercial venture in Venice in the early decades of the seventeenth

century. Early opera was even termed "musica Veneziana"—Venetian

music—in the Italy of the day, and it was not long before productions

of this delightful new music from the north were being performed in

Naples. If you wander into the small maze of streets between

via Medina and via Depretis just west of Piazza Municipio, you will

find via San Bartolomeo. On this street is a tiny church —now

closed— called Santa Maria della Graziella. The church is on the

site of the original opera house of Naples and was opened as the San

Bartolomeo Theater in 1621. It, thus, got in on the beginnings

of opera, begun a few years earlier in Florence and turned into a full-blown

commercial venture in Venice in the early decades of the seventeenth

century. Early opera was even termed "musica Veneziana"—Venetian

music—in the Italy of the day, and it was not long before productions

of this delightful new music from the north were being performed in

Naples.

San Bartolomeo

was destroyed by fire in 1681 but rebuilt at great expense almost immediately,

so important was its cultural contribution to the life of the city.

The theatre was the site where much of the great music of the Neapolitan

Baroque at the turn of the eighteenth century was performed for the

first time—music of Alessandro Scarlatti

and Pergolesi, for example. By the early

decades of the eighteenth century, however, the theater had decayed

so badly that the new monarch from Spain, Charles

III, decided that a new one should be built. When San Carlo was opened in 1737, the old San Bartolomeo

was closed and rebuit as a church. The architect who turned the theater

into a house of worship was Angelo Carasale, the same man who designed

the new theater of San Carlo.

Incoronata,

church

The Church of the Incoronata is on via Medina just a few

yards from Piazza Municipio.

The church gives you a good idea of how the city has changed over the

centuries. It is the oldest church in that part of Naples, stemming

from the 14th century, and is, in fact, the only building from that

century left standing so close to the main square. It is named in honor

of the coronation of Queen Giovanna I, which event took place in 1352.

There is some debate as to whether the church incorporated part of an

earlier building, a Hall of Justice. In any event, beginning with the

Angevins in that century, the street level adjacent to the church underwent

a gradual building up, especially in the early 1500s, when extensive

trench and moat building at nearby Maschio

Angioino produced vast amounts of land fill that was then used

to raise the street level. The modern road is well above the old street

level and entrance to the church. To enter the church today, youhave

to go down some steps. All other buildings on via Medina on both

sides of the street are at the higher street level. The Church of the Incoronata is on via Medina just a few

yards from Piazza Municipio.

The church gives you a good idea of how the city has changed over the

centuries. It is the oldest church in that part of Naples, stemming

from the 14th century, and is, in fact, the only building from that

century left standing so close to the main square. It is named in honor

of the coronation of Queen Giovanna I, which event took place in 1352.

There is some debate as to whether the church incorporated part of an

earlier building, a Hall of Justice. In any event, beginning with the

Angevins in that century, the street level adjacent to the church underwent

a gradual building up, especially in the early 1500s, when extensive

trench and moat building at nearby Maschio

Angioino produced vast amounts of land fill that was then used

to raise the street level. The modern road is well above the old street

level and entrance to the church. To enter the church today, youhave

to go down some steps. All other buildings on via Medina on both

sides of the street are at the higher street level.

To add

insult to injury, the entire church became the basement for a building

constructed over it in the 1800s. There are photographs of that hybrid

piece of architecture that show the outlines of the original arches

barely visible beneath the more modern façade. Restoration was

started in the 1920s. The building no longer functions as a church,

but is, rather, a historical monument. It was "adopted" recently by

a local school and the school children participate in taking care of

it. When the restoration of the building was complete a few years ago,

indeed it was the school kids who ran the opening exhibit and contributed

most of the photos, sketches, and accounts of the history of the church.

Bourbons

(5), royalty (3); Savoy (3)

After

more than a half–century of all around bad feeling and, recently,

much constitutional debate, members of the ex–royal family of

Italy, deposed by popular referendum in 1946, are once again allowed

to place foot on Italian soil—as private citizens, of course. After

more than a half–century of all around bad feeling and, recently,

much constitutional debate, members of the ex–royal family of

Italy, deposed by popular referendum in 1946, are once again allowed

to place foot on Italian soil—as private citizens, of course.

On Saturday,

Victor Emanuel of the House of Savoy (son of the last king of Italy),

his wife Marina Doria, and their son Emanuel Filbert (photo) will visit

Naples. They had announced their intention to donate a sound system

and furnishings for a new auditorium to the public shelter for the homeless

in Naples that bears the name of Victor Emanuel II, this Victor Emanuel's

great-great-grandfather and the first king of united Italy. The city

of Naples has refused the gift: "They're just private citizens

like anyone else. There won't be anything official, no reception, nothing

like that," said City Hall.

(This,

of course, begs the question of why a private citizen cannot donate

a stereo and some chairs—indeed, whatever he wants—to a

home for the needy.) It remains to be seen how that will play out. (I

am betting the city caves in and takes the gift.) Privately, of course,

they will be well received at the Savoy Club in Naples, no doubt by

some of the very people (a bit older now) who voted for the monarchy

and against the institution of a republic in 1946 (the monarchy carried

the vote in Naples, 10-to-1).

A small

demonstration is planned by those nostalgic for the really ex-monarchy,

the Bourbons, whose Kingdom of Naples

was absorbed kicking and screaming into a united Italy in 1860. The

neo-Bourbon Movement of Naples is apparently going to stand around and

hold slightly rude placards. Says Gennaro de Crescenzo, head of the

organization: "The Savoys meant the end of Naples as a capital and the

beginning of its decline—the beginning of the so-called 'Question

of the South' in Italy, the failure of our factories, the beginning

of emigration from the south, the plundering of Neapolitan coffers,

and the massacre of loyalists—who were defined as "bandits".

Procida

(1)

Modern-day

travelers in the Bay of Naples can sail by and miss the Isle of Procida

as easily as the Greeks did three-thousand years ago. Even from the

vantage point across the bay on the Sorrentine coast or the heights

of Capri, the isle of Procida rides so low in the water that in bad

weather it is hard to spot. At best it looks like a smudged extension

of the mainland. Approaching it dead on from the south, you may not

even recognize it as separate from the neighboring island of Ischia. Modern-day

travelers in the Bay of Naples can sail by and miss the Isle of Procida

as easily as the Greeks did three-thousand years ago. Even from the

vantage point across the bay on the Sorrentine coast or the heights

of Capri, the isle of Procida rides so low in the water that in bad

weather it is hard to spot. At best it looks like a smudged extension

of the mainland. Approaching it dead on from the south, you may not

even recognize it as separate from the neighboring island of Ischia.

Procida

has an equally low figurative profile: compared to the other islands

in the bay, Ischia and Capri, the island is relatively unfrequented

by tourists. And certainly, after the flood of English and German that

accosts your ears on those other islands, you get the distinct and accurate

impression that on Procida, Italian is the native language.

Tourist

brochures about Procida usually read something like this:

| Of

the islands embracing the Gulf of Naples, Procida has best succeeded

in preserving its original, genuine beauty, unpolluted nature

and simplicity of life. This tiny isle, cradled in clear and shining

waters, is a precious jewel case inbosoming natural sceneries

of exquisite green shades, colors of bygone ages, iridescent views,

and a wealth of marvelous sights of a primitive and wild grandeur.

The natural harbors abound with fishing boats, reminders

of the ancient traditions cherished by the inhabitants… |

And so

on. Native Procidians are almost embarrassed by that kind of language.

After all, they pride themselves on not being a tourist Mecca. They

are mainly farmers and sailors. They work for a living and have many

of the same problems as working people anywhere else.

The most

prominent physical feature of the island is the medieval fortress, the

so-called “Terra murata,” set high above the sea on the

eastern approach to the main harbor. It has, over the years, gone

from being a fortress to a penitentiary to what it is today, a monument

open to the public. Besides the main harbor, there are two smaller harbors,

Coricella, set right below the imposing ex-fortress, and Chiaiolella,

a small natural harbor at the southern extreme of the island. Here is

where you can believe the tourist brochures—these two tiny harbors

are truly peaceful and picturesque.

Also worth

a visit is the neighboring islet of Vivara; flanking Procida to

the south-west and connected to it by a bridge, this crescent-shaped

remnant ridge of an ancient volcanic crater is now a nature preserve.

It is also the site of recent archaeology that has uncovered fragments

of Mycenaean pottery, left by Greeks who were there many centuries before

the "original" Greeks colonized the bay.

(Also see

this entry.)

Murolo,

Roberto; Neapolitan Song (3)

The

large double–door entrance to via Cimarosa 25 in the Vomero section

of Naples was half–closed this morning, as is customary when someone

in the household passes away. And—as is customary—a small

white card was affixed to the door. It was written by hand and read,

succintly, "For the death of Roberto Murolo". He was 92. It was, perhaps,

the only non–violent thing that could have happened in Naples

yesterday to push today's visit to the city by the ex–royal family

of Italy, the Savoys, out of the headlines. And it did. The

large double–door entrance to via Cimarosa 25 in the Vomero section

of Naples was half–closed this morning, as is customary when someone

in the household passes away. And—as is customary—a small

white card was affixed to the door. It was written by hand and read,

succintly, "For the death of Roberto Murolo". He was 92. It was, perhaps,

the only non–violent thing that could have happened in Naples

yesterday to push today's visit to the city by the ex–royal family

of Italy, the Savoys, out of the headlines. And it did.

There are

three main reasons why one–thousand miles of Italians—from

the Alps to Sicily—know something about the culture and language

of Naples. The first reason is the great playwright Eduardo

de Filippo, on many a literary critic's "short list" of Those Who

Should Have Got a Nobel Prize But Didn't." The second reason—on

a more popular (and more vital) level—is Italy's greatest film

comic, Antonio de Curtis, known simply as "Totò".

The third reason is Roberto Murolo, the gentle and erudite chronicler

of Neapolitan music and the best–known singer in the twentieth

century of the "Neapolitan Song"

If Murolo

had simply been content to remain a guitarist and singer, he certainly

would have done very well, but he was born to more than that. His father

was the highly–regarded dialect poet Ernesto Murolo, part of the

long tradition of dialect literature that included his own contemporary,

Salvatore di Giacomo, and reached back

through the 18th–century libretti of the Neapolitan Comic Opera

to the 16th–century Pentamarone by Giambattista Basile, and beyond. Thus, Roberto Murolo

was very aware of being part of that tradtion, and his great contribution

to the music of Naples is a scholarly one. He dedicated years of his

life to researching, collecting and documenting Neapolitan music and

in 1963 published what amounted to a musical encyclopedia of the music

of Naples, a 12 LP set containing songs from 1200 to 1962, all carefully

documented and explained and all immaculately sung by Murolo, himself.

He sang in the precise pronunciation of a literary language, quite different

from the uneducated "street sound" that one often associates with the

term "dialect".

Murolo

is not the reason that Neaplitan songs such as 'o sole mio

and Funiculì–Funilulà are known abroad. That

goes back to yet an earlier generation, the years at the turn of the

century when so many Neapolitans emigrated and took their music with

them. Interestingly, however, Murolo was part of the post–WW2

generation of Neapolitan singers who resisted the onslaught of American

popular music and helped keep the traditional music of his native culture

from becoming passé.

Although

he became less active with advanced age, Murolo never really retired.

He took part in the 1993 version of the annual Festival of Italian Popular

Music in San Remo with a song entitled "L'Italia è bella,"

a song against racism and xenophobia. And while "cross cultural" music

is run of the mill today, Murolo was doing that as long ago as 1974,

when he sought out and sang with the great Portughese performer of Fado,

Amalia Rodriguez. Murolo was an inspiration to the "friendly rivals"

of his own generation such as Sergio Bruni and to the younger generation

of singers such as Massimo Ranieri and Pino Daniele, both of whom published

tributes to Murolo in the paper this morning. As with the passing of

Eduardo de Filippo in 1984 and Totò in 1967, there is a very

real sense of loss in Naples today.

|