©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Chinese

restaurants, snow (1)

“I

tre gioni della merla.” If merla meant “eagle”

or “falcon”—some swashbuckling raptor—then The

Three Days of (name of appropriate winged warrior) might be the

name of a good spy thriller. However, merla is merely the feminine

form of merlo—blackbird—and “The Three Days

of the Female Blackbird” refers to the three days just behind

us, the last three in January, traditionally regarded as the coldest

days of the year. I have read that the basis of this expression is found

in an old Lombard legend, but I haven’t been able to verify this,

myself, since the Lombards haven’t been a power in Italy in 1000

years and are certainly all dead. I do know of a person in Naples whose

name is about as Lombard as you can get without actually being “Lombard”.

It’s “Ostrogoth”. He might know. “I

tre gioni della merla.” If merla meant “eagle”

or “falcon”—some swashbuckling raptor—then The

Three Days of (name of appropriate winged warrior) might be the

name of a good spy thriller. However, merla is merely the feminine

form of merlo—blackbird—and “The Three Days

of the Female Blackbird” refers to the three days just behind

us, the last three in January, traditionally regarded as the coldest

days of the year. I have read that the basis of this expression is found

in an old Lombard legend, but I haven’t been able to verify this,

myself, since the Lombards haven’t been a power in Italy in 1000

years and are certainly all dead. I do know of a person in Naples whose

name is about as Lombard as you can get without actually being “Lombard”.

It’s “Ostrogoth”. He might know.

The legend

was right on this year. The last three days have been the coldest in

Naples since winter started. There was snow on Vesuvius for the first

time; it was spread down about one-third of the slope, meaning that

the snow line must have been at about 2000 feet, low enough to powder

the tops of the hills along the Sorrentine peninsula and all of the

mountains surrounding Naples, itself. It didn’t snow any at sea-level,

but we did get hail, and the temperature was cold enough to keep the

hail on the ground for a while. It covered the walkways along the seafront

and was enough like snow for a short time to enable kids to scoop together

a slush-ball or two.

Speaking

of female blackbirds, this is the first day of the Year of the Goat

in the Chinese lunar calendar. (Indeed, it was too much to hope that

they might actually have A Year of the Blackbird or Crow or Raven or

at least a Year of the Smooth Segue.) It’s time to go down to

the nearby Chinese restaurant and say good-bye to the family that runs

it; they are going back to China after years in Naples. I remember when

there were absolutely no Chinese restaurants in the city. Then, about

20 years ago, they started to roll in. There seemed to be well over

a dozen of them. Then, a lot of them closed. Now there are 3 or 4 that

I know of. Maybe the ones that left simply made enough money to be able

to return home, as is the wish of so many immigrants. Naples and southern

Italy, in general—having sent millions of persons abroad over

the years to seek work and a new life—is now in the unaccustomed

position, itself, of being somewhat of a magnet for immigrants.

San Carlo

(2)—

I see that the New

York Times had an item yesterday about the appropriateness of booing

at the opera. In Naples, that is not up for discussion. Let's assume

that you are a lowbrow knuckle-dragging cultural yahoo, the kind of

guy who would have met Mother Theresa and said, "Hey, howya doin', Sister—here,

have a beer!" Then you will be happy to learn that the San Carlo Theater can still can still be as rough

and tumble as it was when Mark Twain was here in 1869. He described

the audience at San Carlo as "…three thousand miscreants…

[with]…all the vile, mean traits there are". I see that the New

York Times had an item yesterday about the appropriateness of booing

at the opera. In Naples, that is not up for discussion. Let's assume

that you are a lowbrow knuckle-dragging cultural yahoo, the kind of

guy who would have met Mother Theresa and said, "Hey, howya doin', Sister—here,

have a beer!" Then you will be happy to learn that the San Carlo Theater can still can still be as rough

and tumble as it was when Mark Twain was here in 1869. He described

the audience at San Carlo as "…three thousand miscreants…

[with]…all the vile, mean traits there are".

[The

entire excerpt on Naples from The Innocents Abroad may be viewed

by clicking here.]

San

Carlo has always been what they called in the days of vaudeville a "tough

house". Far from being the refined types we imagine opera-goers to be—signalling

severe disapproval by lofting their eyebrows into little arches of arrogance

and delicately "aheming" once or twice— Neapolitans boo, whistle

at, and heckle the performers. If the performer is doing all right,

then the public heckle one another, just for something to do. I have

seen them cat–call the scenery when the opening curtain went up,

just to let the singers quivering off–stage know what was in store

for them.

Way back

in 1816, for example, Rossini chose

to premiere his Barber of Seville in Rome instead of Naples although

at the time he was actually in charge of San Carlo. His opera was a

reworking of an already beloved opera of the same name by the popular

Neapolitan composer Giovanni Paisiello.

Rossini, aware that the hometown crowd resented his efforts, thought

that he might escape their wrath by opening away from Naples. It didn't

work. Paisiello fans from Naples—"opera hooligans," to use a more

modern and thoroughly appropriate term—followed him and disrupted

the premiere of what has since come to be regarded as one of the greatest

works of the comic opera genre. And later, in 1901, local critics panned

their own hometown boy, Enrico Caruso,

so severely that he took umbrage and then took himself to America, never

to sing in Naples again.

In the

1960's, the San Carlo audience was so unforgiving to the soprano in

Madame Butterfly, that she gave the whole house the local version

of the "finger"— the "horns," right from center stage. One

time, tenor Franco Corelli actually ran off the stage at San Carlo to

get a heckler. And when the baritone in Pagliacci delivered the

opening line of the opera, a rhetorical question to an on–stage

audience assembled for a carnival: "Si può?" (“May

I begin?”), someone in the real-life audience at San Carlo shouted

"No!" Similarly, a line towards the end of La Boheme

has the tenor singing, "I can no longer stay." Someone in the upper

boxes saw that as a straight line for his own jibe: "So leave!"

And at

the end of the 1991/92 season, Francesco Cilea's Adriana Lecouvreur

went along for a few acts, not sailing along, mind you, but not

exactly sinking, either. Local and little known tenor Nunzio Todisco

was singing opposite the great, if fading, prima donna, soprano Raina

Kabaivanska. Nothing special. Maybe the costumes were a little

out-of-epoch, that sort of thing, but nothing that couldn't be salvaged

by some good singing. Then, third act: festive scene in the villa of

the Prince of Bouillon. The majordomo gives the cue for the tenor's

appearance by announcing the arrival of the Count of Saxony, played

by our main man Nunzio: "Il conte di Sassonia!" Ta–taaa!

No Count. There follow a few very one–sided duets with an imaginary

tenor, before maestro Daniel Oren calls down the curtain and sets off

to find the real thing.

Nunzio

has been sulking in the dressing room, having the classic opera singer's

breakdown, tantrum, paroxysm, fit of pique, outburst of irascibility

and display of ill temper. "I can't go on!" he thunders, moans,

laments and bleeds. (Yes, a thesaurus is every opera critic's best friend.)

His crisis is due to his perception that the crowd is stacked like the

Tower of Pisa. They are clearly on the soprano's side, he says, and

out to ambush him. His critics would later say that he was having trouble

with his part, so he just choked. Anyway, maestro gives him a pep talk

and trots him back out for the rest of the opera, announcing to the

audience that in spite of "indisposition," the tenor would valiantly

carry on. That is like telling vultures that the carrion delivery van

is in the neighborhood.

When he

got back out there, they heckled him. He gave as good as he got, however,

resorting, in kind, to foul language and asking the Kabaivanska fans

in one box how much they had been paid to root for her. Arms were

seen reaching out from the wings frantically trying to wave him off

the stage. In vaudeville, they used a hook. At one point, a fist-fight

threatened to erupt between opposing fans, and the glorious highlight

of the evening was the appearance of doubled–barrelled "horns"—one

of the most vulgar gestures you can make in Italian society—a

lady in a box was flashing both hands out to the entire house, waggling

them around to one and all like obscene little antennae.

After the

opera, Nunzio was unrepentant. He called his leading lady an "old chicken"

and said that the only reason she had any fans at all was that her husband

bussed them in, getting them to attend by promising free pizza afterwards.

This was an unforgivable Blowing of One's Cool. His contract was broken

for the remainder of the run, and an understudy carried on. Also, he

was sued by various parties for Defamation of Character and Not Being

Nice to a Soprano.

[See here

for a separate item on San Carlo.]

Neapolitan

culture (5), economics, Eurispes

Eurispes,

the European Institute of Political, Economic, and Social Studies is

an Italian think tank that, in its own words: Eurispes,

the European Institute of Political, Economic, and Social Studies is

an Italian think tank that, in its own words:

| Since

1982, conducts research and other scientific initiatives in the

political, legal, economic, social, culture and communications

areas such as:

a)

The Italian Report: an annual publication that portrays the

Italian System through multidisciplinary analysis from macro

sociological point of view; the document constitutes a precious

instrument for political theoreticians, economic and social

policy makers and in the information world;

b)

Permanent scientific studies: criminality, infancy and adolescence,

schools;

c)

Analysis and interpretation of political and social dynamics;

d)

Planning and implementing theories and instrumentation for communication;

e)

Analysis and evaluation of politics;

f)

Analysis and studies of production systems.

|

The organization

has just issued its annual Italian Report, and the Neapolitan daily,

il Mattino, devoted quite bit of space yesterday to the economic part

of the report. Essentially, things have not changed too much over the

years—most of the industry and wealth in Italy is still in the

north, making the historic division between north and south as marked

as ever.

The report

actually divides the nation into three parts for purposes of comparison.

In the north, 2.4% of the population lives below the poverty level;

there is an unemployment rate of 3.8%. Those figures for central Italy

are, respectively, 1.6% and 6.1%. For the south (the territory of the

ex-Kingdom of Naples—that is, south of Rome, from the Gargano

river down to and including the island of Sicily) they are 7.3% and

a staggering 17.9% unemployment rate. In Italy, as a whole, 10% of the

families have 47% of the wealth. Most of those families are in the north.

The most

striking numbers for the south have to do with the so–called “submerged

economy”—that is, the black market. One-third of Italian

wealth is generated by illegal activities, but most of it is in the

south, where there are as many as 11 million illegal workers, and where

70% (!) of manufactured items are counterfeit knock-offs of brand names

or are otherwise illegally produced. Eurispes claims that this will

amount, in 2003, to 130 billion euros in taxes that will not be paid.

The report

doesn’t try to shrink heads. That is, while it does say that one-fourth

of Italians report being depressed, and that most of them are women

in central and northern Italy, Eurispes doesn’t venture any judgement

on the truism that money doesn’t buy happiness. It may have to

do, of course, with the question, itself. If you ask one of those women

in the 10% group that have half the money in Italy if she is depressed—“Of

course, I’m depressed. My cosmetic surgery didn’t work.

I had two chins. Now I have three.” Down here in the south—“I

don’t have time to be depressed, you moron. I have five kids and

my husband is out of work.”

All in

all, the submerged economy in Naples seems to lend a sort of free-wheeling

atmosphere to a place where there is—at least, officially—so

little money. Everyone hustles something, and people spend what they

have. On a normal Wednesday evening not so long ago, on one of the main

shopping thoroughfares in the city, a visitor asked me if it was a special

holiday. I said it wasn’t. She said: “Look at all the people

shopping. This looks like 5th Ave in New York the week before Christmas.”

Busses

(2), driving (3)

Busses

in Naples are still as rare as a good metaphor to describe the rareness

of busses in Naples. In the Vomero section of the city, citizens huddle

around rusted markers called "bus stops"—left there by some forgotten

race of Palaeolithic optimists—and talk about the return of bus

number 134 like astronomy students pondering the periodic appearance

of the Ikeya-Seki comet. "I think we have a sighting! She's somewhere

between the orbit of Saturn and Piazza Vanvitelli!" Their collars are

turned up against the wind, their eyes dart nervously around, and they

speak in reverent whispers as if they feared their words might conjure

up the object of their thoughts. This is the Flying Dutchman Syndrome:

it's something you've been waiting for, yes! something you would like

to see, yes!—and are in awe of, yes!—but Holy Mackerel,

that's a Ghost Ship! Do you really want to be there when she heaves

into view?! They converse: "Old One, tell me again how it was when you

saw The Bus.” “Hush, child, don't encourage him; he's been

telling that same tale since the Crusades.” Busses

in Naples are still as rare as a good metaphor to describe the rareness

of busses in Naples. In the Vomero section of the city, citizens huddle

around rusted markers called "bus stops"—left there by some forgotten

race of Palaeolithic optimists—and talk about the return of bus

number 134 like astronomy students pondering the periodic appearance

of the Ikeya-Seki comet. "I think we have a sighting! She's somewhere

between the orbit of Saturn and Piazza Vanvitelli!" Their collars are

turned up against the wind, their eyes dart nervously around, and they

speak in reverent whispers as if they feared their words might conjure

up the object of their thoughts. This is the Flying Dutchman Syndrome:

it's something you've been waiting for, yes! something you would like

to see, yes!—and are in awe of, yes!—but Holy Mackerel,

that's a Ghost Ship! Do you really want to be there when she heaves

into view?! They converse: "Old One, tell me again how it was when you

saw The Bus.” “Hush, child, don't encourage him; he's been

telling that same tale since the Crusades.”

And what

of the peasants down on Corso Vittorio Emanuele who await the C16 quaintly

known as The Twins? The C16 always runs in pairs. The first one comes

along, packed to the gunwales. (The gunwales on a bus are on the roof,

where they keep the spare sardines). A few yards behind comes bus number

two, empty, travelling in its own parallel universe, a happy place,

uncluttered by passengers —yea, the fabled abode of smiling bus

drivers.)

It is not

widely known, but bus schedules in Naples do exist. And handy things

they are, too, since drivers use schedules to set their watches by.

Let's say you are a driver idling your engine waiting to leave on your

2.45 run. Now that the first half of the ball game is finished you can

put the radio away and start to think about pulling out. You glance

at your watch: 3.05. Click. Snap. Beep. Not any more! It's now 2.45,

and away you go! If you are a gambler, there is a bonus in this schedule

stuff. You are a passenger aboard the number 12 at the end–of–the–line,

waiting for the bus to start its 2.50 p.m. run. You look at your watch;

2.50, and vrooooooom!—the bus actually leaves on time! Here, let

me spell that out for you: l–e–a–v–e–s

o–n t–i–m–e. Only a rationalist

fool would fail to see the hand of Providence in this. Get off at the

next stop and run into the nearest lottery shop and play the bus number

plus the two components of the time: 12, 2, 50. (If you try this and

it works, you owe me.)

You can,

of course, do what most people do: forget the bus and drive your car.

The city of Naples, however, now has "green" days. On these days, you

may not drive your car unless it is equipped with a catalytic converter,

thus making it clean and “green”— the color of trees,

meadows, grass, youth, life—and the color of bile, the fluid

secreted by the liver in moments of anger or great bitterness of the

spirit brought on by waiting for a bus. If you drive anyway, you risk

fines and conversation with a traffic cop, a vigile:

| Vigile:

You're not allowed to drive your car today.

Motorist:

Oh, I didn't know that.

Vigile:

It's been in the papers. Besides, ignorance of the law is no

excuse.

Motorist

(sensing the shaky philosophical underpinnings of the vigile's

argument): Of course ignorance of the law is an excuse!

If ignorance of the law were no excuse, we wouldn't even need

laws! We would all be guided by an internal ethical code. We

are not so guided, ergo ignorance of the law is an excuse.

I was ignorant of the law and, double ergo, may not be

punished. Quod erat demonstrandum, copper.

Vigile:

You are going to get fined real good, buddy.

Motorist:

And besides, I have…uh…a caterpillar contorter.

Vigile:

You mean a catalytic converter?

Motorist:

Whatever.

Vigile:

You’re driving a 1975 Fiat that looks like it just went

12 rounds with Theodoric the Ostrogoth, and you have a catalytic

converter? Let's have a look.

Motorist:

Well, I'm not sure it's hooked up properly.

Vigile:

I'd be happy to check it for you.

Motorist:

It's at home.

Vigile:

The law says it has to be attached to the car.

Motorist:

You mean like a seat belt?

Vigile: Exactly.

Motorist:

Oh, I didn't know that.

Vigile:

It's been in the papers. Besides, ignorance of the law is no

excuse. Say, where is your seat belt?

|

And so on.

Eventually, since the fine would have had to come out of the money that

the unemployed war–decorated motorist was saving up to send his

leukaemia–ridden daughter to Lourdes, things worked out. The vigile

let him off with a warning, and the motorist chugged away, happily generating

lots of hydrocarbons and promising on the soul of his sainted grandmother—who

once pulled a vigile from a burning vehicle—to take the bus next

time.

Neapolitan

culture (6), snow (2)—

Naples

as Winter Wonderland doesn’t happen too often—once a decade,

perhaps—but it actually snowed at sea level this morning. The

upper elevations of the city, Vomero at 600 feet, were covered with

snow, and the hermitage of Camaldoli at about 1200 feet on the

hill in back of the city looked like a postcard from Austria. Vesuvius,

of course, is appropriately picturesque. Naples

as Winter Wonderland doesn’t happen too often—once a decade,

perhaps—but it actually snowed at sea level this morning. The

upper elevations of the city, Vomero at 600 feet, were covered with

snow, and the hermitage of Camaldoli at about 1200 feet on the

hill in back of the city looked like a postcard from Austria. Vesuvius,

of course, is appropriately picturesque.

Item two:

The morning paper happily notes the presence of some local people in

the new supplement of the Treccani encyclopedia, somewhat the standard

reference work in Italian and the one you have on your shelf when you

want to look something or someone up. The last complete edition came

out in 1997. This year’s update includes, among Neapolitans, Olympic

swimmer Massimiliano Rosolino; author Luciano De Crescenzo; and photographer,

Mimmo Iodice. It includes also, for the first time, a horse!—Varenne,

the trotter (recently retired and happily munching clover somewhere),

winner of 60 races in 70 starts. The paper is unclear on whether or

not Varenne is from Naples and, if so, exactly why he would have a French

name.

Bourbons

(4)

For

those Neapolitans who are tired of traffic, noise, and maybe just the

general daily rigmarole, there are still some genteel pursuits at hand.

One of these is worrying about the problems of the other Charles and

Camilla—of the royal house of Bourbon, the dynasty that ruled

the Kingdom of Naples between the 1730s and 1860. The dynasty, of course,

is, as they say, “in abeyance,” meaning out–of–work.

Carlo and Camilla are what is left of the dynasty, but the princess

is about to remedy that situation in June, when she will give birth.

(I’m really not sure if she’s a princess. It seems to me

that if you marry a prince, that makes you a princess—but what

do I know. I went to the MGM School of History. I’m a barbarian.) For

those Neapolitans who are tired of traffic, noise, and maybe just the

general daily rigmarole, there are still some genteel pursuits at hand.

One of these is worrying about the problems of the other Charles and

Camilla—of the royal house of Bourbon, the dynasty that ruled

the Kingdom of Naples between the 1730s and 1860. The dynasty, of course,

is, as they say, “in abeyance,” meaning out–of–work.

Carlo and Camilla are what is left of the dynasty, but the princess

is about to remedy that situation in June, when she will give birth.

(I’m really not sure if she’s a princess. It seems to me

that if you marry a prince, that makes you a princess—but what

do I know. I went to the MGM School of History. I’m a barbarian.)

Interestingly,

when they were married in 1998, they wanted to have the ceremony in

the great palace of Caserta (photo), that splendid “Versailles

of Italy” built by Vanvitelli in the 1700s. Lamely citing “bureaucratic

obstacles,” the superintendent of said national treasure refused

them that little bit of bizarre, if harmless, counter–revolutionary

nostalgia, so they went to Monaco. The prince kindly directed those

desiring to do so—in lieu of gifts—to donate to the very

active charity in Naples run by Mother Theresa’s Sisters of Calcutta.

This step no doubt raised him a few notches even in the eyes of republican

cynics and those whose only Bourbon acquaintance is Jack Daniels.

For what

it’s worth, the dynastic question is complicated. There is, in

fact, still an operating Bourbon dynasty in Europe in the person of

King Juan Carlos of Spain (born in Rome, by the way), a descendant of

Phillip V, the first Bourbon King of Spain following the Wars of the

Spanish Succession in the early 1700s, and also the grandfather of Charles III, the first Bourbon King of Naples, an

ancestor of the current “virtual” king Charles. This makes

the current Neapolitan Charles and the current King of Spain—let’s

see…carry the two…uh—umpteenth cousins much removed.

However—and here is where it gets interesting—the Spanish

and Italian Bourbons separated into different dynasties in the 1700s,

and depending on how one interprets the subsequent documents that are

said to have ratified this division, the soon–to–be–born

new Bourbon may or may not actually be the king who would some day rule

the Kingdom of Naples if it existed—which it doesn’t.

I think

I’m going outside to check on the traffic, noise and general daily

rigmarole.

Cell-phones

(2)

The

long, cold Neapolitan winter is over. 'O paese d' 'o sole—“The

Land of the Sun,” as they say in Neapolitan—has returned.

I looked out the window this morning and thought, Oh, no! My eyes

have turned to cobalt—but I'm…so…young. Fortunately,

it was just a bright, cerulean day over the entire Gulf of Naples, and

the only snow left was the white, crystal diadem on Vesuvius. The weather

should stay like this, oh, at least until the day after tomorrow, when

another cold front will move down from Rekjavik. In a scant few tens

of millions of years, the tectonic plate I live on will have pushed

the Alps up high enough to block this sort of illicit cold weather from

the north. I can’t wait. The

long, cold Neapolitan winter is over. 'O paese d' 'o sole—“The

Land of the Sun,” as they say in Neapolitan—has returned.

I looked out the window this morning and thought, Oh, no! My eyes

have turned to cobalt—but I'm…so…young. Fortunately,

it was just a bright, cerulean day over the entire Gulf of Naples, and

the only snow left was the white, crystal diadem on Vesuvius. The weather

should stay like this, oh, at least until the day after tomorrow, when

another cold front will move down from Rekjavik. In a scant few tens

of millions of years, the tectonic plate I live on will have pushed

the Alps up high enough to block this sort of illicit cold weather from

the north. I can’t wait.

Yes, it

was a glorious day to be cut off from the world. They turned off my

telephone. I know that most people already have some sort of chip implanted

in their brains so they are always in contact. They can always call

and be called, disturb and be disturbed, and are evermore bereft of

the inner silence, a silence never jangled by tinny, electronic versions

of Mozart’s Turkish March going off in your molars when

there is “incoming”. I weep for these people, for they will

never know the sense of freedom that I am feeling at this moment.

(Three

hours later)—I have just gone out and bought a cell phone. I couldn’t

take it.

Six words:

Don’t mess with the phone company. (If contractions count as two

words, that makes seven, I know—as in the Seven Last Words of

Christ. My Aramaic friends tell me that a rough translation of those

Seven Last Words is: Do Not Mess With The Phone Company.) All we told

them was that we didn’t like them anymore and were switching to

a more efficient private carrier. Zap. They turned off the ADSL line

a month early and the phone today. I think they can do that, and that

even if I were a centipede, I wouldn’t have a leg to stand on

in any sort of a legal showdown.

I am reminded

of the case, a few years ago, of a Neapolitan doctor, Ermanno Russo.

He had a cell phone installed in his car. He used it primarily to keep

in contact with his patients in the Naples area. His phone bills ran

to about 400–450 thousand lire for the two-month billing period

(In those fine pre-Euro days, that was about 200–225 dollars.

So far, so good. He then got active in politics, ran for office and,

lo and behold, his first phone bill after the election was for one and

one–half million lire. Hmmm, thinks Ermanno, this, too, is possible.

After all, I was on the phone a lot during the campaign.

It is only

when the next phone bill arrives—for three million lire! ($1500)—that

he decides to pay a call on SIP, the phone company. Their records show

that he has called Brazil, Venezuela, Canada, Jupiter and various other

places where, one, he has no patients, and, two, was not running for

office.

"But…but…,"

stammers Russo. "I don't even keep teenagers in my car. How is this

possible? Maybe something has gone wrong with your system!"

He hits

a stone wall quarried in Carrara. Gone wrong? Look, they say, smiling

at him down those long bureaucratic noses of patient disdain,

this is not some fallible human agency you are dealing with. This is

The Phone Company. F as in Father, S as in Son, and Holy

Spirit as in Phone Company. Do you understand? they ask, mouthing

each syllable carefully so as not to overtax their client's limited

mental faculties. They tell Russo, heh–heh, that he should be

more careful about letting others use his mobile phone. Russo

then takes the phone out of his car, field–strips it and trots

the pieces down to the police station, hands them to the coppers and

says,"Here, watch these for me". Then, with his Star Trek walkie–talkie

safely under gendarme lock and key, his next phone bill is for eight

million lire! Then, as they say, the SIP hit the fan.

After furious

electronic sleuthing, authorities traced Russo's phone woes to

a local doctor cum hacker who figured out how to

patch his own phone into the frequencies used by the—at the time—new

cellular telephones. All you needed, he said, was lots of computer smarts

and some sucker's number, and, boy, did he ever have Russo's number.

It started as a prank, said he, and then, as the word spread among his

own circle of freeloading friends, it got out of hand.

These days,

the phone company says not to worry about it. They have the situation

under control. Now, about this swamp land I'm selling…

Hold on.

There goes my molar.

Angevin

Fortress (Maschio Angioino)

I finally got to take a tour of the Maschio Angioino,

the great Angevin Fortress, down at the port of Naples. It's the first

time that I have actually been in, around and over the premises and

allowed to indulge my inner twelve-year-old—that is, to

get up there on the ramparts behind the battlement where they keep the

merlons, crenels, ballistrarias and bartizan turrets. For those of you

who know less about medieval fortress architecture than you should,

that is the place you stood to pour the boiling oil on the invaders. I finally got to take a tour of the Maschio Angioino,

the great Angevin Fortress, down at the port of Naples. It's the first

time that I have actually been in, around and over the premises and

allowed to indulge my inner twelve-year-old—that is, to

get up there on the ramparts behind the battlement where they keep the

merlons, crenels, ballistrarias and bartizan turrets. For those of you

who know less about medieval fortress architecture than you should,

that is the place you stood to pour the boiling oil on the invaders.

The fortress

is also called the Castelnuovo (New Castle) to distinguish it

from the older Castel dell'Ovo.

It was built by the Angevin King Charles I as the new royal palace when

he moved the capital of the kingdom from Palermo to Naples in the 13th

century. Only a few bits of the original structure have remained over

the centuries, such as the Palatina Chapel. The original structure was

built in only four years and was finished in 1282. It then fell into

disrepair, accelerated by an earthquake; thus, the structure you see

today is a makeover started by the Aragonese in the 1450s and completed

by the Spanish in the mid-1500s.

The

castle has seen a number of events highly significant in the history

of the city. In 1294, the castle was the scene of the abdication of

Pope Celestine V. At least in Dante's version of the afterlife, Celestine

resides in Hell. The Divine Comedy places him just past the gates

of Hell among the Opportunists—(in John Ciardi's translation)—"...the

nearly soulless whose lives concluded neither blame nor praise...[and

in reference to Celestine]...I recognized the shadow of that soul

who, in his cowardice, made the Grand Denial...". (To play the Pope's

advocate, I remind you that Dante was really upset at the fact that

Celestine, by quitting, left the door open to the subsequent Pope, Boniface

VIII, corrupt and, in Dante's view, responsible for much of the evils

that befell Dante's city of Florence.) The

castle has seen a number of events highly significant in the history

of the city. In 1294, the castle was the scene of the abdication of

Pope Celestine V. At least in Dante's version of the afterlife, Celestine

resides in Hell. The Divine Comedy places him just past the gates

of Hell among the Opportunists—(in John Ciardi's translation)—"...the

nearly soulless whose lives concluded neither blame nor praise...[and

in reference to Celestine]...I recognized the shadow of that soul

who, in his cowardice, made the Grand Denial...". (To play the Pope's

advocate, I remind you that Dante was really upset at the fact that

Celestine, by quitting, left the door open to the subsequent Pope, Boniface

VIII, corrupt and, in Dante's view, responsible for much of the evils

that befell Dante's city of Florence.)

Here,

too, in 1486, the infamous Baron's Plot against the king was brought

to a conclusion with the arrest of the conspirators. Also, in the 1300s,

during the great flowering of Italian medieval literature, King Robert

of Anjou received such eminent poets as Petrarch and Boccaccio. Inside

the castle is a vast courtyard, a 14th century portico, and the elegant

facade of the Palatina Chapel. Although Giotto and his pupils did the

original frescoes inside the chapel, very little of their work remains

today. Much of the sculpture seen on the grounds is from the Aragonese

period (the mid-1400s) and is the work of disciples of Donatello. Here,

too, in 1486, the infamous Baron's Plot against the king was brought

to a conclusion with the arrest of the conspirators. Also, in the 1300s,

during the great flowering of Italian medieval literature, King Robert

of Anjou received such eminent poets as Petrarch and Boccaccio. Inside

the castle is a vast courtyard, a 14th century portico, and the elegant

facade of the Palatina Chapel. Although Giotto and his pupils did the

original frescoes inside the chapel, very little of their work remains

today. Much of the sculpture seen on the grounds is from the Aragonese

period (the mid-1400s) and is the work of disciples of Donatello.

Popular

legend says that a crocodile used to prowl the dungeon; it feasted on

upstart barons who incurred the wrath of the Aragonese king. Accepting

the idea of a renegade Egyptian crocodile jumping ship in the port of

Naples in the Middle Ages and settling down in the castle requires some

suspension of disbelief, admittedly. Yet, it's a good story and no doubt

served to keep potential trouble makers in line. The moat that surrounds

the building was, apparently, just a defensive ditch and was never filled

with water.

Very

recent archaeology has laid bare the structures that were on the site

before the Angevins moved in to build their castle: (1) the foundations

of a Franciscan convent that was torn down (the residents were given

property for a new convent that still stands, the Church of Santa Maria

La Nova); (2) Roman baths. The site was part of a vast complex running

along the shore to the height of Pizzofalcone and around to the small

isle of Megaride, site of the Egg Castle and presumed site of the villa

of Licinius Lucullus, the Roman consul whose festive life-style has

given us the expression, "Lucullan splendor". Very

recent archaeology has laid bare the structures that were on the site

before the Angevins moved in to build their castle: (1) the foundations

of a Franciscan convent that was torn down (the residents were given

property for a new convent that still stands, the Church of Santa Maria

La Nova); (2) Roman baths. The site was part of a vast complex running

along the shore to the height of Pizzofalcone and around to the small

isle of Megaride, site of the Egg Castle and presumed site of the villa

of Licinius Lucullus, the Roman consul whose festive life-style has

given us the expression, "Lucullan splendor".

As of this

writing, considerable work has gone to opening the fortress to the public

and to push the structure back into the historical consciousness of

Neapolitans. It is, after all, the first royal residence in the city,

even though it was overshadowed by later Spanish palaces and, then,

the great Royal Palace of the Bourbons. At present, The Palatina Chapel

is open, as is the Civic museum, which houses an art collection. Also,

a part of the collection of the Filangieri Museum from downtown Naples

has been set up on the premises while that museum is closed for repairs.

The castle hosts periodic conventions and the Naples City Council convenes

there.

Funiculì-funiculà,

music (4)

Everyone has had the experience of being obsessed with

and possessed by a melody. It takes you completely unawares—most

likely a little jingle that somehow slipped down behind the sofa cushions

of your mind once upon a time and now, responding to the call of the

mysterious Heavenly Hoover, is sucked up unbidden and unwelcome into

your consciousness. Suddenly you're helpless. You have no control over

your own brain. A diabolical zombie tunesmith is throwing the switches

of your limbic system, gleefully rerouting the same melody over and

over and over, turning your noggin from the crowning achievement of

God's Creation into a useless carousel, wearing grooves in your head

and wasting valuable synaptic connections that could be better spent

trying to remember important things such as the molecular structure

of testosterone, for example. Everyone has had the experience of being obsessed with

and possessed by a melody. It takes you completely unawares—most

likely a little jingle that somehow slipped down behind the sofa cushions

of your mind once upon a time and now, responding to the call of the

mysterious Heavenly Hoover, is sucked up unbidden and unwelcome into

your consciousness. Suddenly you're helpless. You have no control over

your own brain. A diabolical zombie tunesmith is throwing the switches

of your limbic system, gleefully rerouting the same melody over and

over and over, turning your noggin from the crowning achievement of

God's Creation into a useless carousel, wearing grooves in your head

and wasting valuable synaptic connections that could be better spent

trying to remember important things such as the molecular structure

of testosterone, for example.

It is not

clear exactly what it is that gives a tune that ability to move in with

you as wholeheartedly as your in–laws and take over so completely,

but the rhythms of some songs seem to be specially crafted for it. Lilting

little waltzes like Ach, Du Lieber Augustine, for example.

DUM

dee duh duh / DUM duh dum /DUM duh dum / DUM duh dum

DUM dee duh duh / DUM duh dum /DUM duh dum / DUM !

Next

on the all–time list of songs you'll need an exorcist to get rid

of happens to be one of the national anthems of Naples. Unlike many

Neapolitan songs that dwell on unrequited love or warm evenings spent

trying to find the requited kind, Funiculì Funiculà

is a snappy happy little march about going up the side of a volcano.

Almost everyone knows the melody and at least some version of the lyrics,

many of which were written by sniggering boy–scouts when they

should have been practicing their knots and are, therefore, quite unrepeatable

around high class folks like yourselves, so forget it. Next

on the all–time list of songs you'll need an exorcist to get rid

of happens to be one of the national anthems of Naples. Unlike many

Neapolitan songs that dwell on unrequited love or warm evenings spent

trying to find the requited kind, Funiculì Funiculà

is a snappy happy little march about going up the side of a volcano.

Almost everyone knows the melody and at least some version of the lyrics,

many of which were written by sniggering boy–scouts when they

should have been practicing their knots and are, therefore, quite unrepeatable

around high class folks like yourselves, so forget it.

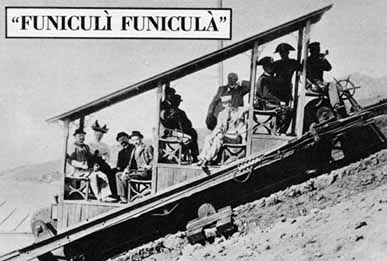

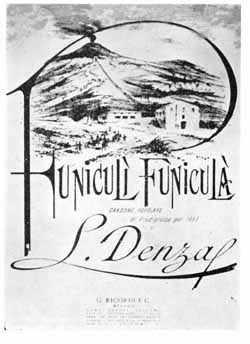

In 1880,

a cable–car, or funicular railway, was opened on the slopes of

Vesuvius; for the occasion, Giuseppe Turco, a noted journalist of the

day, and Luigi Danza turned out the lyrics and melody, respectively.

The melody opens on a lively fanfare interval of a fourth: ta–taah!

and then carries on. The text in the original Neapolitan dialect starts:

"Aissera,

Nanninè, me ne sagliette/ tu saie addò! / tu saie addò!

Addò sto core 'ngrato chiu dispiette/ farme nun pò/

farme nun pò/"

Now the

verse does speak of escaping up the slopes of Vesuvius to get away from

"your ungrateful heart" (it wouldn't be a Neapolitan song without at

least lip service to the doctrine of faithlessness), but the real ambush

comes a few measures later when that famous refrain starts playing raquetball

against the inside of your skull:

"JAMmo,

JAMmo, 'nCOPpa jammo JA…/

JAMmo, JAMmo, 'nCOPpa jammo JA…/

FunicuLI FunicuLA FunicuLI FunicuLAAAA/

'nCOPpa jammo JA… FunicuLI FunicuLAAAAAA!"

What this

means—in a feeble attempt to show that profundity is in inverse

proportion to the square of obsessiveness—is: "LET'S go, LET'S

go, LET'S go to the TOP!"

It works

perfectly. Boy, does it ever. This is the refrain that took the 1880's

crowd by storm, hereabouts. When the funicular started its regular runs

up to the top ("'ncoppa") of Mt. Vesuvius, one imagines hordes of volcano

berserkers hanging out the windows, denting the downbeats into the sides

of the carriages and bellowing "DAAAH–dum DAAAH–dum", winding

up on the inspired open–throated nonsense syllable, "LAAAA!" with

an obsessive ferocity that makes one absolutely nostalgic for the enchanting

strains of "A Hundred Bottles of Beer on the Wall". And unlike the titanic

battle that Mr. Nasenbaum in Beginning Physics swore would shape up

at encounters of this nature, when the irresistible trochaic force of

this song meets the immovable object of your head, it ain't even close.

You get hammered. Undoubtedly, Neapolitan mothers in the1880's spent

much of their time shouting: "Will you kids shut up with that song!"

(Or was it: "SHUT up, SHUT up, SHUT up with that SONG! Damn! Now you've

got me doing it!")

They're

still doing it. And so are the rest of us. I heard it again the other

day and now it's up there, riding the cable–car in my head, going

round and round. The original cable–car, by the way, has been

dismantled. It had been having its ups and downs over the years. There

is some talk of rebuilding it. I can't wait.

CAN'T wait

/ CAN'T wait.

Help.

[Complete

texts in dialect to a number of Neapolitan songs may be found by

clicking here.]

"Nile"

(square & statue); Sant’Angelo

a Nilo (church)

The name

"Nile"—curiously, no doubt—occurs in Neapolitan toponymy.

There is a small Nile Square where you find the Church of Sant’Angelo

a Nilo, as well as a statue of a Nile river god. The church is the

only one in Naples with a name that gives such obvious testimony to

the bonds that the Greek founders of the original city had with their

own cultural forerunners, the Egyptians; the word ‘Nilo’

does, in fact, mean Nile. Here was the ‘Alexandrian (Egyptian)

Quarter’ of the original Greek city.

The Church goes back to 1384 when it was built by Cardinal

Rinaldo Brancaccio. Most of the physical structure visible today, however—the

facade, for example—is the result of work done in the early 1500s.

The works within the church bear the stamp almost entirely of the Brancaccio

family, throughout the centuries the only true patrons of this church.

The tomb of Cardinal Brancaccio within the church is one of the most

important examples of Renaissance sculpture in Naples. It was done by

Donatello and Michelozzi in Tuscany, where the executor of Brancacio’s

will, Cosimo dei Medici, then had it transferred to the church in Naples. The Church goes back to 1384 when it was built by Cardinal

Rinaldo Brancaccio. Most of the physical structure visible today, however—the

facade, for example—is the result of work done in the early 1500s.

The works within the church bear the stamp almost entirely of the Brancaccio

family, throughout the centuries the only true patrons of this church.

The tomb of Cardinal Brancaccio within the church is one of the most

important examples of Renaissance sculpture in Naples. It was done by

Donatello and Michelozzi in Tuscany, where the executor of Brancacio’s

will, Cosimo dei Medici, then had it transferred to the church in Naples.

Nearby, the small statue, itself, was restored and cleaned up a few

years ago, but now, again, stands in what looks like a semi-abandoned

state. There is scaffolding on the adjacent building and a tin-roof

shelter has had to be erected to protect the statue; that has proved

to be a convenient stall for a few itinerant vendors. Well, sooner or

later…

To understand

why there should be anything at all in Naples named for the Nile river,

it helps to remember that our inherited body of Greco-Roman myth is

at least partially Egypto-Greco-Roman. There were, for example, at the

time of Christ, a number of Temples of Serapis throughout the Roman

Empire. That Roman cult is directly traceable back through the Greeks

to the Egyptian worship of Isis and Osiris. (However, the so-called

'Temple of Serapis,' in Pozzuoli, we now know, was just a market-place.)

The statue,

this lesser known example of Egyptian influence in Naples, is of an

old merman-like figure reclining on his pedestal. It is at the approximate

spot where the colony of Egyptians from Alexandria settled in the days

of Nero, well after the incorporation of Naples into the dominion of

Rome. Here the Egyptians erected a statue, possibly for veneration,

of the God of the Nile, the river that played such an important part

in the mythology of their own native culture.

The statue

disappeared for centuries following the advent of Christianity in the

Roman Empire. It was not until the 1100s that it was uncovered—headless—during

construction of an early kind of town–hall for the area. (The

name—"Nilo"—of the general area had stuck through the centuries

even in the absence of the statue.) That building was eventually demolished

in the1600s and the statue was moved to the center of the square where

it still stands. At that time a sculptor was hired to add the head;

the statue was restored again in 1734, and a plaque, in Latin, was added

to commemorate the restoration.

Given the

importance of water, particularly rivers, in much world mythology—and

especially the importance of the Nile to the Egyptians—it is not

surprising that settlers from Egypt would have brought the Nile with

them to Naples. They chose a city by the sea, but also one that had

a river of its own at the time, the Sebeto, which then flowed through

the eastern part of Naples.

Even without

the head, the original statue would have been easy to identify as a

chimera, that fantastical patchwork of more than one creature, something

common to many mythologies. It is likely to have been a representation

of Creation, and the original head might have been that of a crocodile,

making it the man-crocodile, Sobek, the Egyptian river God. Possible,

too, is that it was another chimera, Ammut, the god that devoured the

souls of the condemned, and a composite of crocodile, lioness and hippopotamus.

The creature represented by the statue would in both cases have been

similar to those in much sacred literature—"leviathan," in the

Bible, for example, or in Canaanite and Babylonian mythology, where

the Creator conquers a dragon or sea-monster representing primordial

Chaos.

The Nile figure

in Naples is resting on sand, (perhaps rising out of "primordial mud"),

making the "sea monster" interpretation plausible. Yet, in spite of

the paws on the body of the statue— clearly identifying it as

at least part beast—the 17th century sculptor chose to restore

the statue with the head of a man. This might simply have been an attempt

to re–establish the gender of the statue, which many had mistaken

for a goddess of some sort when it was rediscovered. It might, however,

have been a conscious attempt to make the statue resemble the Egyptian

god, Nun, god of the original waters before the Creation and often depicted

as an old man with a beard, a sign of virility. Also, the figure holds

a cornucopia, a widespread symbol of abundance, probably stemming from

'horn' ('corno-') as the symbol of a bull and thus the source of virility,

fertility and abundance—all of which makes the 'Creator' interpretation

just as plausible as that of the 'sea monster'. The Nile figure

in Naples is resting on sand, (perhaps rising out of "primordial mud"),

making the "sea monster" interpretation plausible. Yet, in spite of

the paws on the body of the statue— clearly identifying it as

at least part beast—the 17th century sculptor chose to restore

the statue with the head of a man. This might simply have been an attempt

to re–establish the gender of the statue, which many had mistaken

for a goddess of some sort when it was rediscovered. It might, however,

have been a conscious attempt to make the statue resemble the Egyptian

god, Nun, god of the original waters before the Creation and often depicted

as an old man with a beard, a sign of virility. Also, the figure holds

a cornucopia, a widespread symbol of abundance, probably stemming from

'horn' ('corno-') as the symbol of a bull and thus the source of virility,

fertility and abundance—all of which makes the 'Creator' interpretation

just as plausible as that of the 'sea monster'.

During

the Middle Ages, the square of the Nile became the center of one of

the city's administrative districts ('sedili'), called Tocco

Maggiore, or in Latin, Toccum capitis platae, meaning the

"zone of large houses and wide streets". Since there is an Italian word

very similar to nilo --'nido' (meaning 'nest), which can be taken

to mean 'house'—Nilo was understandably transformed into 'nido'

in the minds of many, thus losing a sense of the original name. It is

still common to hear the square misidentified as 'nido'.

For reasons

that are unclear, the statue has come to be called Cuórpo'

e Napule in Neapolitan dialect (Corpo di Napoli, in Italian)—the

Body of Naples— and the statue and the site have long been objects

of popular 'worship'. The famous 18th-century magician, Cagliostro,

even made a pilgrimage to it. During the recent reconstruction, many

lottery tickets and votive scribblings were found wedged in between

the paws.

Surrounded

by so many later and larger monuments in the downtown area, this small

statue is easy to overlook. Its origin and history, too, are much less

certain than that of more recent artifacts, yet, perhaps that is what

gives it a peculiar charm. In a 2,500-year-old city, there are bound

to be many tiny mysteries that captivate, precisely because they are

enigmatic.

(To

see map of the historic center of Naples: click

here. The church and statue are # 17 and 19, respectively.)

Campi

Flegrei

The

Phlegrean Fields

"The

Breath of the Lord, like a stream of brimstone..."

- Isaiah xxx, 33.

Somewhere

there's a German—(is that a song title?)—who, if he ever

thinks of me at all, remembers me simply as as the joker who gave him

a bum steer (taurus impecuniosus) about the Fiery Fields of Naples,

the Phlegrean Fields, the Campi Flegrei.

We were

sharing a metro carriage, stopped and apparently wintering over in Fuorigrotta,

when I noticed a young man with an Erich von Stroheim scalpcut, dueling

scar and monocle, humming The Ride of the Valkyries under

his breath and holding a guidebook to Naples upside down. I approached

and asked in my best Gothic, "Are you please to be in dire straits of

information, nicht wahr? "

"Zese

are ze Phlegrean Fields, ja?" he snapped.

"Uh, yeah,"

I said, in that authoritative Baedecker baritone that is well-known

to those who know and love me, for I, too, had seen the Campi Flegrei

sign on the station platform. Spent by the intimacy of conversation,

he clicked his heels and got off in gratitude. (I was later to get off

in Bagnoli). As we pulled out, I noticed him noticing that he

was surrounded by Fiats and cement. I last saw him dolefully

rummaging through newsstand post-cards looking for exploding volcanos

and similar stuff that had made Goethe swoon, sturm und drang

a century and a half earlier.

I now know

that I put young Siegfried off the train at least two stops

too early. (Who could blame him if he has since dedicated his life to

taking revenge on unsuspecting tourists by standing outside the

Black Forest Gasthaus in the middle of Hamburg and telling them, "Why,

sure, the headwaters of the Danube are right over there. It says "Black

Forest," doesn't it? Heh-heh-heh.")

Monte

Nuovo and Lake Lucrino in the Campi Flegrei

The

Campi Flegrei is a cauldron of volcanic origin extending from

the heights of Posillipo in the south to Cuma

in the north and inland a number of miles. It is a welter of extinct

craters, bubbling sulfur pits, underground thermal springs, skewed hills

and sudden jagged upcroppings of tufa and solidified lava. The

Campi Flegrei is a cauldron of volcanic origin extending from

the heights of Posillipo in the south to Cuma

in the north and inland a number of miles. It is a welter of extinct

craters, bubbling sulfur pits, underground thermal springs, skewed hills

and sudden jagged upcroppings of tufa and solidified lava.

The best

way to see this geological freakshow as a single unit is to get

some high ground. Parco Virgiliano is ideal for this. The park

is on the Posillipo ridge overlooking the island of Nisida and offers

a clear view over to the other side of the bay, Cape Miseno, and inland

to the Astroni, which is the wildlife reserve and park above Agnano.

Lake Miseno, by the way, was an important port for the imperial Roman fleet. There is a lighthouse on the

cape, a modern descendant of the one that guided Roman sailors. The

highest point in the Phlegrean Fields is Camaldoli.

It is home to a hermitage, prominently visible from anywhere in the

area, perched as it is, 458 meters above sea-level. It is open to visitors

and offers another clear and broad panorama of the Fields.

Monte

Nuovo (see photo), near Arco Felice, is another remarkable

feature of the Campi Flegrei. The name means "new mountain" and

is entirely appropriate. It was born in a matter of days, beginning

early in the morning of September 29, 1538. In geological terms,

mountains don't come much newer than that, or if they do, try to be

elsewhere when it happens. A Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom

of the Two Sicilies published in Naples in 1816 recounts that the

eruption destroyed a local town and a hospital. It also cites the proverbial

wisdom that "grass doesn't grow on Monte Nuovo," then points out how

off the mark that bit of folk wisdom is -- there is grass, not to mention

trees, all over Monte Nuovo, says the enyclopedist. (For a separate

item on the geology of the Bay of Naples, click

here.)

Solfatara

is the ever bubbling sulfur pit just south of Pozzuoli; it is one of the greatest tourist attractions

in the area. Sulfur fumaroles vent themselves all over the place, and

you may see entire families out for a Sunday stroll suddenly stop and

run over to one and stick their heads right into the stygian stench.

These are not practitioners of some cult of Neo-Nasal Masochism, for

besides use in vulcanizing rubber, making matches, gunpowder, insecticides

and industrial-grade brimstone to pave the "broad way to destruction"

with, sulfur has putative healing powers, so if the stuff shoots up

right beside the road, free for the snorting, why should you pay for

the privilege at one of the many spas around town? (Also see here.)

Also, if someone has told you to go to Hell recently, Lake Averno is

on the left as you leave Pozzuoli and head north up the via Domiziana.

From World Literature, you will remember that this is the mythological

descent to the underworld, mentioned by Virgil

in the Aeneid. Speaking of which: Cuma, home to Aeneas

after his wanderings and the first Greek settlement on the Italian mainland,

is the last prominent "bump" on the Phlegrean landscape before it smooths

out onto the plain that goes north towards Gaeta. If there is room for

only one cultural "must" on your list, there is something wrong with

you, but, anyway, Cuma is it. For those of you who fall into the psychological

trap of telescoping all ancient civilizations into one convenient mind-frame

(as in: "the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans"), remember that two

thousand years ago, an ancient Roman stood where you are standing and

marveled at Cuma because the ancient Greeks had built it.

The Campi

Flegrei have fascinated travelers for centuries. When Charles Dickens

was here, he said:

"The

fairest country in the world is spread about us. Whether we turn towards

the Miseno shore of the splendid watery amphitheatre, and go by the

Grotto of Posillipo to the Grotta del Cane (Dog) and away to Baiae,

or take the other way, towards Vesuvius and Sorrento, it is one succession

of delights."

A

less poetic view of the Grotto of the Dog is provided by Mark Twain,

who claimed he was all fired up to really try and suffocate one of man's

best friends in the Grotto's famed noxious vapors. He couldn't manage

to chase down a victim. [Click here for

that Mark Twain passage from The Innocents Abroad.] I'm not going

to tell you where that particular place is. Find it yourself. Look for

the metro stop that says Campi Flegrei. Then, ask a stranger.

Floridiana,

Villa

I see that

the City Hall is currently struggling with the demands of environmentalists,

who are demanding that steps be taken to protect one of city's few great

parks, The Villa Floridiana. It is not nearly as well-known as the Villa

Comunale, the Public Gardens, down on the sea-front, or the vast

grounds of the Capodimonte Museum, one of the royal palaces of the

Bourbons from the 18th–century.

For a start, the Floridiana will be put under the auspices of the Naples

Superintendency of Museums, and an initial 150 thousand euros have been

allocated for maintenance and repairs of the grounds. Also, it seems

that the employees of the Floridiana—a dozen or so—like

to use the grounds as their own private parking lot. After all, when

they come to work in the morning, there is generally no place on the

street to park. They certainly can't be expected to use the nearby garages;

they would have to pay, and we can't have that.

The Villa Floridiana, today one of the favorite public

parks in Naples, commands a pleasant view of the bay from its

position on the slopes of the Vomero section of the city. The villa

dates back to 1816 when Ferdinand I of Bourbon, King of the Two

Sicilies, acquired the property from Giuseppe Caracciolo, Prince

of Torella. The King then donated the property as the site for

a vacation residence to his favorite lady, Luisa Migliaccio Partanna,

duchess of Floridia, from which the villa has taken its

name. (She was the king's "morganatic" * wife and did all right; she

later got a second residence from Ferdinand, the Palazzo Partanna. The

King's first wife, Caroline, died in 1814.) The Villa Floridiana, today one of the favorite public

parks in Naples, commands a pleasant view of the bay from its

position on the slopes of the Vomero section of the city. The villa

dates back to 1816 when Ferdinand I of Bourbon, King of the Two

Sicilies, acquired the property from Giuseppe Caracciolo, Prince

of Torella. The King then donated the property as the site for

a vacation residence to his favorite lady, Luisa Migliaccio Partanna,

duchess of Floridia, from which the villa has taken its

name. (She was the king's "morganatic" * wife and did all right; she

later got a second residence from Ferdinand, the Palazzo Partanna. The

King's first wife, Caroline, died in 1814.)

The neoclassical

residence and surrounding gardens were then planned and built from 1817-19.

Numerous wooded trails wind through the park and there are over a hundred

species of trees, flowers and plants. The original picturesque

and romantic setting was amplified by the addition of statues, fountains,

an outdoor theater, a temple and even a fake ruin or two to heighten

the effect of Classicism. Although much of this original splendour has

decayed, the natural wooded beauty of the park remains, as does the

Villa, itself. The Villa currently houses the Duke of Martina

National Museum of Ceramics (photo), with an important collection of

both European and Oriental items.

*morganatic:

an unusual term with a fascinating etymology, from matrimonium morganaticum,

literally "marriage with a morning gift," referring to a gift given

to the wife on the day of marriage, in lieu of any share in the husband's

property. The term designated a form of marriage in which a nobleman

married a woman of lower social status with the provision that, although

children would be legitimate, neither they nor the wife might lay claim

to the husband's rank or property.

Driving

(4)

"Follow

those who do not drive as well as you do and kill them!"—Attila

the Hun

Remember

Driver Education? My favorite film in that class was the cartoon about

Mr.Walker and Mr. Wheeler. The former, a good–natured goofy pedestrian,

needed but to slip behind the wheel of his car to have his Jekyll &

Hyde button punched, thus werewolfing into Mr. Wheeler (get it?), crazed

motorist who delights in using his Mercedes–Benzoid hood–ornament

as cross–hairs to mow down little old ladies in cross–walks.

Good stuff, that, and like most wheel–happy adolescents of my

generation, I was one hundred–and–ten percent on the side

of Evil: we all rooted for Mr. Wheeler, much to the dismay of our Driver

Ed instructor. But why listen to a driver with a name like Ed Instructor?

After all, this was the same guy who wouldn't let you shift into high

gear until you got out of the school parking lot. Remember

Driver Education? My favorite film in that class was the cartoon about

Mr.Walker and Mr. Wheeler. The former, a good–natured goofy pedestrian,

needed but to slip behind the wheel of his car to have his Jekyll &

Hyde button punched, thus werewolfing into Mr. Wheeler (get it?), crazed

motorist who delights in using his Mercedes–Benzoid hood–ornament

as cross–hairs to mow down little old ladies in cross–walks.

Good stuff, that, and like most wheel–happy adolescents of my

generation, I was one hundred–and–ten percent on the side

of Evil: we all rooted for Mr. Wheeler, much to the dismay of our Driver

Ed instructor. But why listen to a driver with a name like Ed Instructor?

After all, this was the same guy who wouldn't let you shift into high

gear until you got out of the school parking lot.

Luckily

I have moved to Naples, the Promised Land of wheel–happy adolescents

and now I get to Wheeler out quite frequently. As a matter of fact,

it is getting… more… and more… difficult… to

… change back… don't know… how much… longer

I can… can… hold out…!

(An unspecified

amount of time later.)

(Slap–slap.

Whiskey–whiskey.) Thanks, I needed that. I was saying: I have

done things in Neapolitan traffic, that if I were a traffic cop, I would

chase me down and pull me over, revoke my license forever, tell the

car crusher to leave my vehicle a squat and steaming cube of scrap on

the roadside, and frog–march me in sackcloth to the nearest bicycle

shop.

All this

can be yours. If you want to drive like me, and if you can get them

to let you out on weekends, you have come to the right place. Follow

these rules:

One. Traffic

lights. The only rule about traffic lights in Naples is, "Never run

a green one". I remember a taxi driver telling me in those soft homespun

tones that come naturally when you're accelerating through hospital

zones just what those beautiful colored lights on street corners really

meant to him, sniff, especially at Christmas time: "Sure 'n' 'tis enuf

to bring a tear to the eyes of this son of the auld sod," he whispered.

(Besides traffic lights, he was terrible at geography.) I have actually

stopped for red and been shouted at, on the order of: "Go back to Germany,

you mindless robot tool of the authoritarian overlords! I bet you obey

signs that say No Smoking, Keep Off The Grass, and No Radioactive Waste

Dumping, too! Don't you realize that we are engaged in a ceaseless libertarian

struggle against forces which would squelch individual liberties and

impose…" The rest dopplered down below the range of human hearing

as he sped around me.

Two. You

must absolutely learn to smoke at filling stations. Everyone else does,

even —especially—the guy who is filling your tank. Maybe

he knows something you don't—perhaps that petroleum products are

not flammable, (especially that watered–down brew he's dumping

in your car). I don't care if you're a health nut and have never smoked

in your life, or have sworn off, or think that it's a foul and noxious

vice. Look. Compromise. You don't even have to inhale. (You may not

have time for that, anyway.) At least once in your life you must feel

that top–gun macho rush of adrenalin that comes from lighting

up just as the first whiff of gasoline from the pump hits your nostrils.

True, only God can make a tree, but you can make filling stations explode.

Three.

Learn how to make love in a Fiat 500 (coitus contortius). What, you

rightfully ask, does this have to do with driving? Am I not catering,

nay, pandering to the sophomoric droolers among us to even broach the

subject? You got that right, parry I with Socratic precision. If you

find the whole topic distasteful, you may be interested in a refined

variation. You will need a friend who can drive a fast motorcycle extremely

well, while you sit on the back and lob water–filled balloons

into parked passionmobile through the sun–roofs, which young lovers

inevitably leave open. This is humor of the lowest brow, barely worthy

of early Cromagnon woodshop majors, and, personally, I wouldn't be caught

dead doing it. "Not being caught dead" is the operative phrase, here.

Remember: fast bike, good driver.

Four. Go

the wrong way on one–way streets. When the traffic cop pulls you

over, waggle your cigar, groucho your eye–brows at him and say:

"What's the problem, officer? I was only going one way!" He will chuckle,

tell you some World's Oldest Jokes in Italian and let you off with a

mere blow on the kneecap.

Five. Drive

on side–walks. This is technically legal, since none of the streets

work. Six: Only tourists make U–turns; you should try W's and

B's. There are also a number of letters in the Book of Kells and the

Arabic alphabet worth looking into. This will require study on your

part. Seven: double–park. Eight: triple–park. Nine: Practice

your car horn whenever possible. Remember, that's how Paganini started.

Ten: Remember that silence is golden, yes, but scriptures tell us that

the Great Whore of the Apocalypse will be dressed in gold. You wouldn't

want to look like that, would you?

Valentine's

Day

The

worldwide hodge–podging of holidays is careening right along in

Naples. They dress up for Halloween, are already asking me what time

they should be over for Thanksgiving dinner later this year, and I fully

expect Robert E. Lee's birthday and St. Patrick's Day to wind up on

the calendar sooner or later. Yes, little Confederate Leprechauns will

someday take their rightful place—right next to Barbie—in

the traditional Neapolitan representation of the Nativity, the presepe. The

worldwide hodge–podging of holidays is careening right along in

Naples. They dress up for Halloween, are already asking me what time

they should be over for Thanksgiving dinner later this year, and I fully

expect Robert E. Lee's birthday and St. Patrick's Day to wind up on

the calendar sooner or later. Yes, little Confederate Leprechauns will

someday take their rightful place—right next to Barbie—in

the traditional Neapolitan representation of the Nativity, the presepe.

Today,

St. Valentine's Day, is another one of those holidays that no one around

here used to celebrate. At least Valentine is not a foreign import.

He, indeed, was a priest in Rome during the reign of Claudius II Gothicus

in the third century. He was beheaded, they say, on February 14, not

just for refusing to give up his faith, but for refusing to stop performing

Christian marriage rites in an age when Christianity was still a covert

faith. Until 1969, the day was a feast day in the Roman Catholic calendar;

now, however, the secularisation is complete. Paraphernalia of St. Valentine's

Day is evident in all the shops in Naples: stylized bouquets with heart–shaped

candies in place of flowers, €50 heart-shaped boxes of chocolates,

cards, little teddy-bears with the words "Ti amo" ("I love you")

embossed on them, and a special newspaper insert bearing paid–for,

personal declarations of love. There was also an article about the commercialisation

of holidays.

There is

some bad news about Valentine's Day: the heart is not an accurate metaphor

for the emotion we associate with this day. Love is really controlled

by the thalamus, an "ovoid mass of nuclei" in the brain. There is, however,

good news: If you are in love, it doesn't really matter, and, anyway,

it's much easier to make a paper cut-out of a heart than it is of an

ovoid mass of nuclei—and finding even a bad rhyme for "thalamus"

would just about put the Hallmark people out of business. (No, don't

bother. I've been trying for days. So far, I have come up with: "I hope

there's nothing with my gal/pal amiss; won't you be my thalamus.")

I

was once invited to speak on a "Valentine-related topic". The drab bureaucratic

clunk of that phrase struck me. You can have "work related," "accident

related," "defence related," "budget related," "alcohol related," and

so forth—things which make you tired, sorry or disliked by others—but

I truly believe that you cannot have "Valentine related," without doing

mayhem to the spirit of the season. I

was once invited to speak on a "Valentine-related topic". The drab bureaucratic

clunk of that phrase struck me. You can have "work related," "accident

related," "defence related," "budget related," "alcohol related," and

so forth—things which make you tired, sorry or disliked by others—but

I truly believe that you cannot have "Valentine related," without doing

mayhem to the spirit of the season.

It would

be nice to believe that the day of Lovers is named for Valentine

because he died doing what Lovers do best. Alas, that is not the case.

We associate lovers with his day because of early groups of English

bird watchers. Even back in prehistoric times, they were a race of bird

fanciers. They would stand around the Sceptered Isle in their bowlers

and loin cloths peering through the liquid sunshine at Red or Periwinkle

Breasted or Crested Warblers or Throckmortons. They noticed that birds

took their mates on or about this date. By the time of Chaucer, it was

well established. He recounts in his delightful A Parliament of Fowls,

how all the birds come together on Valentine's Day and discuss which

of them is the best mate. Does love soar like an eagle? Strut like a

peacock? Is it a turkey? Or is it simply quack, quack, waddle over there

and get it done as quickly as possible? In any event, says Chaucer:

For

this was sent on Seynt Valentyne's day

Whan every foul cometh ther to choose his mate. |

Whatever

love is, it is the most besung of human emotions. Read the words of

one known in the 19th-century in America as "The Great Agnostic," Robert

Ingersoll, someone who was honest enough to say that he didn't know

about certain things, but who knew that…

| Love

is the morning and the evening star. It is the air and light of

every heart, builder of every home and kindler of every fire on

every hearth. Love is the magician and enchanter that changes

worthless things to joy and makes royal kings and queens of common

clay. Without that sacred passion we are less than beasts; with

it, earth is heaven and we are gods. |

Islands

This

is less of an island than it is a large unnamed rock sticking up

off the eastern end of Capri. I don't think it is for sale.

|

There

are a number of small islands in and around the Bay of Naples that are,

or have been, privately owned. One that comes to mind is the postage-stamp-sized

main island of I Galli (the Gulls). The other "gulls" are

little more than rocks sticking up out of the water, but the main gull

has a grand villa on it. At one time or another, island and house have

been in the possession of the family of Eduardo de Filippo, the Neapolitan

playwright, as well as Rudolf Nuryev, the Russian ballet star. The island

is outside the bay on the other side of the Sorrentine peninsula in the

area where a number of small rocks in the water are named for the sirens

in the Odyssey. At least some of the waters are part of a new national

park, Punta Campanella, named for the tip of the Sorrentine peninsula,

so it is not clear to me whether or not the island is still in private

hands. There

are a number of small islands in and around the Bay of Naples that are,