© 2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.comAround

Naples in English

|

| The bones of St. Andrew, enclosed in three beautifully decorated cases, emanate an extraordinary substance: Manna. |

I don't

know quite what to make of that. Manna is one of the many things I know

very little about, but I had always thought it referred to the substance

mentioned in the 16th chapter of Exodus, the food miraculously supplied

to the Children of Israel during their 40 years of wandering in the

wilderness:

| …and it was like coriander seed, white; and the taste of it was like wafers made with honey... |

My

OED now tells me, however, that "manna" is also

| A sweet pale yellow or whitish concrete juice obtained from incisions in the bark of the Manna-ash, Fraxinus Ornus, chiefly in Calabria and Sicily; used in medicine as a gentle laxative. Also, a similar exudation obtained from other plants. |

I am not sure what all that means. I am irreverently—but briefly—reminded of Mark Twain's comment that Christ had 12 disciples and that 13 of them are buried in Germany. I suppose it is equally irreverent to suppose that the bones of a dead person—even a saint—might provide food for those so inclined. I shall have to let that go for a while.

The item that really caught my attention was the statue of a bird (see photo, above), standing upright, wings outspread, high enough (about five feet) to partially occlude the lectern it was placed in front of. The tour-guide who had known every little thing about every handle and hinge on the bronze doors of the cathedral tried to drag us right by the bird with no comment. I asked. She didn't know. Fine, it happens. No hard feelings, but I had to know.

It was clearly out of place, gray and drab —but totally surrounded by splendor. The first problem was to figure out what kind of bird it was. The wings were no help. They looked angelic and out-of-place on any avian species I remembered—except for that race of Hawk Men in the old Flash Gordon serials from the 1930s.

The

eagle, the symbol of St. John, from the Book of Kells

What

birds are symbolic in the Christian faith? That might help. The list

is impressive: the dove, eagle, pelican, stork, crane, swan, and even

the vulture (sometimes allegorized as the purifier of the world and

the vanquisher of the infernal serpent). More obvious is the mythological

phoenix seen as a symbol of Christ and His resurrection. In general,

the flight of the bird represents the soul as opposed to the earthbound

body, and in art there are many depictions of the infant Jesus holding

a bird in his hand, suggesting the idea of the soul incarnated in the

body. There are abundant passages in scripture that mention birds:

What

birds are symbolic in the Christian faith? That might help. The list

is impressive: the dove, eagle, pelican, stork, crane, swan, and even

the vulture (sometimes allegorized as the purifier of the world and

the vanquisher of the infernal serpent). More obvious is the mythological

phoenix seen as a symbol of Christ and His resurrection. In general,

the flight of the bird represents the soul as opposed to the earthbound

body, and in art there are many depictions of the infant Jesus holding

a bird in his hand, suggesting the idea of the soul incarnated in the

body. There are abundant passages in scripture that mention birds:

| —Be

ye therefore wise as serpents and simple as doves. (Matt. 10:16)

—They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings as eagles." (Isa. 40: 31) —As an eagle stirreth up her nest, fluttereth over her young, spreadeth abroad her wings, taketh them, beareth them on her wings; so the Lord alone did lead him." (Deut.32: 10-12) —And the Holy Ghost descended in a bodily shape like a dove upon him...(Luke 3:22) even —The wings of the ostrich flap joyfully, but they cannot compare with the pinions and feathers of the stork. (Job: 39:13) |

And so on. It is very long and complicated list to thresh out for allegorists. The statue in the Amalfi cathedral really didn't look like a dove, which had been my first intuition. An eagle? Maybe. My wife was of the opinion that it looked like some kind of a "stretched chicken".

"Hah. There

are no chickens in Christian symbolism," I said profoundly.

"What about where Jesus says to Peter: 'The cock shall not crow till

thou hast denied me thrice.'?"

"A cock is not a chicken."

"A cock is Mr. Chicken."

A cock is Mr. Chicken. Uxorial hermeneutics can be enlightening at times. Assuming this not to have been one of those times, I put Mr. Chicken on the back-burner with the Hawk Men.

I called the Amalfi archdiocese and spoke to a knowledgeable young man. Indeed, the statue is of an eagle and represents St. John the Evangelist. Every evangelist is represented by an animal. The eagle represents St. John because in his Gospel, St. John sees with the unflinching eye of an eagle the highest truths in the divinity of Christ, the Redeemer. The statue seemed—was—out of place because it had, in fact, been moved to be in front of a lectern in the main part of the church in keeping with this spirit of the Evangelist, the preacher. Originally, the statue had been in the baptistery. The eagle, it seems, is a symbol of baptism, as well. It was a belief among the ancients that the eagle could renew its youth by plunging three times into pure water. Indeed, Terence Hanbury White's translation of a 12th-century bestiary tells us:

| ..when the eagle grows old and his wings become heavy and his eyes become darkened with a mist, then he goes in search of a fountain...and he dips himself three times in it and he is renewed with a great vigour of plumage and slendour of vision...Do the same thing, O Man, you who are clothed in the old garment and have the eyes of your heart growing foggy. Seek for the spiritual fountain of the Lord... |

And in the 103rd Psalm, David says:

| ...who

satisfieth thy mouth with good things so that your youth is renewed like the eagle's... |

Volcanoes (3)

Maybe

they are trying to tell us something. There are 19 towns in the area

around Vesuvius known as the "Red Zone". That is the area that will

have to be evacuated in case of an eruption. There are about 600,000

persons living in the Red Zone. The communities at risk are now prepared

to offer €25,000 (about $30,000) towards a new place to live to

anyone who leaves the area. They call it Project Exodus and the hope

is that the project will reduce the population by one-third.

Maybe

they are trying to tell us something. There are 19 towns in the area

around Vesuvius known as the "Red Zone". That is the area that will

have to be evacuated in case of an eruption. There are about 600,000

persons living in the Red Zone. The communities at risk are now prepared

to offer €25,000 (about $30,000) towards a new place to live to

anyone who leaves the area. They call it Project Exodus and the hope

is that the project will reduce the population by one-third.

The "to

anyone" details are not at all clear. No one seems to know whether it

applies, say, to all family members in the same house or apartment—almost

certainly not the case—or if it even applies to those who rent

as opposed to those who own. It probably means that a single sum will

go to a single owner. I suspect that there will not be many takers.

Those who buy property around a volcano—at least in Naples—are

characteristically fatalistic about the future; you might be tempting

providence by taking the money. ("Oh, trying to pull a fast one, eh?

Where's my thunderbolt.")

Death, culture of

One

of those things that seem to happen only in films about Naples

actually happened yesterday. Fortunato Iorio is 30 years old, the father

of three children and has been unemployed for months. In January he

started underscoring his plight by displaying himself dressed in full

funereal garb, laid out in a coffin, and surrounded by flowers, his

faithful dog, and by weeping "mourners"—his friends and relatives

sympathetic to his situation. He lies there and they wail and keen slogans

such as "He might as well be dead without a job". Fortunato has even

founded an organization called Principle and Dignity, dedicated to helping

those in his same situation.

One

of those things that seem to happen only in films about Naples

actually happened yesterday. Fortunato Iorio is 30 years old, the father

of three children and has been unemployed for months. In January he

started underscoring his plight by displaying himself dressed in full

funereal garb, laid out in a coffin, and surrounded by flowers, his

faithful dog, and by weeping "mourners"—his friends and relatives

sympathetic to his situation. He lies there and they wail and keen slogans

such as "He might as well be dead without a job". Fortunato has even

founded an organization called Principle and Dignity, dedicated to helping

those in his same situation.

He was

on display again yesterday in downtown Naples, being carried along,

dead as a live doornail, by his pallbearer pals when they ran into a

real funeral procession. Fortunato did the right thing, of course,

which was to sit upright and make a respectful genuflection in the direction

of the real thing, after which he died back down again. The incident

was not reported as having caused any harsh words to pass from the direction

of the truly bereft. That may be—as I note in another entry—due to the often less-than-serious

view of death in Naples. There is often an air of perfunctory tragedy

about it.

university (1)

The main building of the University of Naples is on Corso Umberto,

one block east of Piazza Borsa. The building was erected between

1897 and 1908 as part of the massive urban

renewal of that portion of the city, which saw the construction

of the main boulevard, itself.

Officially, the university is named for Frederick II of Swabia, the Holy Roman Emperor, who founded the university in the thirteenth century. It is, thus, one of the oldest such institutions in Europe. Originally, the premises of the university were at the nearby church of San Domenico Maggiore. This was at the time when Thomas Aquinas (1225-74) taught theology there. The University was moved in 1615 to the building that now houses the National Museum. It moved from there to its present location off of Corso Umberto in 1777, moving into what had been a Jesuit monastery and college. That structure was the Chiostro del Salvatore, built in the late 1500s. The main university building on Corso Umberto is simply a front for that older building behind it, which now houses the university library. [More on other ex-monasteries.]

The entire

complex is vast, stretching up the hill towards Piazza San

Domenico Maggiore; it is one modern city block wide, as well, and

includes the university library and a number of museums of natural history.

Near the main building, across Corso Umberto, the University

has additional space in the ex-monastery of San Pietro Martire, originally

a Dominican establishment until closed in 1808. That two-level monastery,

built in 1590, was entirely restored in 1979.

Abu Tabela

I

see that there is a bed and breakfast organization near the Amalfi coast.

That is not surprising, nor is the fact they advertise quaint little

hikes into the very beautiful surrounding countryside, some of them

quite close to the Fjord of Furore. One such hike

that caught my eye was billed as "Along the trail of Abu Tabela". The

blurb says, "…our goal is the small town square of San Lazzaro."

It praises the "blessed peace and quiet" of the area. (The town square

of San Lazzaro [photo], above the Amalfi coast, is still named for "General

Avitabile", hometown hero famous in Afghan lore as "Abu Tabela".)

I

see that there is a bed and breakfast organization near the Amalfi coast.

That is not surprising, nor is the fact they advertise quaint little

hikes into the very beautiful surrounding countryside, some of them

quite close to the Fjord of Furore. One such hike

that caught my eye was billed as "Along the trail of Abu Tabela". The

blurb says, "…our goal is the small town square of San Lazzaro."

It praises the "blessed peace and quiet" of the area. (The town square

of San Lazzaro [photo], above the Amalfi coast, is still named for "General

Avitabile", hometown hero famous in Afghan lore as "Abu Tabela".)

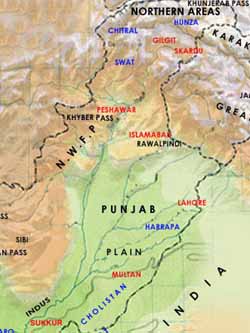

As it turns out, Abu Tabela was anything but quaint—and his life has very little to do with peace and quite, either, except the sombre peace and quiet brought on by death. He is the subject of a recent book by Stefano Malatesta entitled Abu Tabela, The Neapolitan Who Tamed the Afghans. If you are attracted by stories of Attila the Hun and Vlad the Impaler, you will like Abu Tamela, born Paolo Crescenzo Martino Avitabile in 1791 in the mountains above Amalfi in the then Bourbon Kingdom of Naples. How "Avitabile" turned into "Abu Tabela" and why that latter name is still used by mothers in Peshawar (in modern-day Pakistan) almost two centuries after the fact to control unruly children ("If you don't stop shut up, I'm going to call Abu Tabela")—that is a strange story.

At the age of 16, Avitabile enlisted in the Bourbon army. He soon passed into the new Neapolitan army of Gioacchino Murat, who had been made King of Naples by his brother-in-law, Napoleon Bonaparte, after the royal family fled to Sicily. When Napoleon's time had come and gone, Avitabile returned to service with the restored Bourbon military.

In

the early 1820s, however, he set out for parts east as a soldier of

fortune. He sold his services to the Shah of Persia and was apparently

successful in forcing the Kurdish population to pay their taxes. Then

in the late 1820s, when the great Sikh warrior Ranjit Singh captured

Peshawar (map, left), Avitabile went to work up there, right near the

infamous Khyber Pass, that beautiful vantage point and dead-end street

for many an invader of the Indian sub-continent. One of the stories

they tell about Singh is that despite his many conquests, he did not

allow wanton destruction of life or property, and that throughout his

life he never passed a sentence of death. I am unable to reconcile that

benign image with his employing a cut-throat such as Avitabile (local

pronunciation changed that to "Abu Tabela") as the govenor of the city

of Peshawar. Avitabile quickly earned the reputation of being a bloodthirsty

and ruthless enforcer of Sikh authority. Every morning, they say, Avitabile

would have a few Muslims thrown to their deaths from a minaret just

as a warning to the locals. He meted out absolutely gruesome "justice"

as governor of Peshawar, something that no doubt helped to drive the

population away from the city; the population of Peshawar was reduced

by half in the years of Sikh rule.

In

the early 1820s, however, he set out for parts east as a soldier of

fortune. He sold his services to the Shah of Persia and was apparently

successful in forcing the Kurdish population to pay their taxes. Then

in the late 1820s, when the great Sikh warrior Ranjit Singh captured

Peshawar (map, left), Avitabile went to work up there, right near the

infamous Khyber Pass, that beautiful vantage point and dead-end street

for many an invader of the Indian sub-continent. One of the stories

they tell about Singh is that despite his many conquests, he did not

allow wanton destruction of life or property, and that throughout his

life he never passed a sentence of death. I am unable to reconcile that

benign image with his employing a cut-throat such as Avitabile (local

pronunciation changed that to "Abu Tabela") as the govenor of the city

of Peshawar. Avitabile quickly earned the reputation of being a bloodthirsty

and ruthless enforcer of Sikh authority. Every morning, they say, Avitabile

would have a few Muslims thrown to their deaths from a minaret just

as a warning to the locals. He meted out absolutely gruesome "justice"

as governor of Peshawar, something that no doubt helped to drive the

population away from the city; the population of Peshawar was reduced

by half in the years of Sikh rule.

Avitabile got rich in Peshawar and, unlike many European soldiers-of-fortune in Asia, he had saved his money. He returned to Italy in the early 1840s. On the way back, he stopped for a while in England, where he was received by none other than Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington (1769-1852). (Between 1845 and 1849, the British would fight two so-called "Sikh Wars," campaigns that led to the conquest and annexation of the Punjab into British India. Perhaps the Duke was eager for details from one who had "tamed" the Afghans. (Hmmm. Sound familiar?)

Abu Tabela

then went home to the hills of Amalfi, where he bought himself a nice

place to live and married a woman much younger than himself. She and

her lover—one of the servants— poisoned Avitabile in 1850.

It probably happened in one of those quaint little Bed and Breakfast

places, too.

Nunziatella

The military college Nunziatella is the prominent red building

that sits over the bay of Naples and that part of town known as Chiaia.

It was founded by Ferdinand IV in 1787 as an academy to train the officer

corps for the Kingdom of Naples. Originally, the building was erected

in 1588 by Anna Mendozza Marchesana della Valle, a noblewoman who then

gave the building to the Jesuit Order. The premises served as a novitiate

until the Jesuits were banned from the kingdom in the mid-1700s.

The military college Nunziatella is the prominent red building

that sits over the bay of Naples and that part of town known as Chiaia.

It was founded by Ferdinand IV in 1787 as an academy to train the officer

corps for the Kingdom of Naples. Originally, the building was erected

in 1588 by Anna Mendozza Marchesana della Valle, a noblewoman who then

gave the building to the Jesuit Order. The premises served as a novitiate

until the Jesuits were banned from the kingdom in the mid-1700s.

Shortly after its founding, students and faculty of the Nunziatella (so named for the chapel annex on the grounds of the academy—literally, "Little Church of the Annunciation") overwhelmingly supported the fledgeling and short-lived Parthenopean Republic. However, the revolution in France had, by that time, already devoured its children and the Neapolitan equivalent fared no better. The monarchy was restored and the Nunziatella was punished for its revolutionary fervor by a temporary demotion to the role of boarding school.

A far greater—ultimately fatal—danger to the Kingdom arose half a century later when the spirit of Italian unification swept the peninsula. Like all conflicts of this kind —close cousins to civil wars—this one commanded fierce and divided loyalties. In Naples, officer graduates of the Nunziatella were torn between fighting for their King and siding with the forces of Giuseppe Garibaldi, inexorably moving up the boot of Italy from their landing in Sicily with the truly revolutionary idea of one nation, united from the Ionian Sea to the Alps.

With unification came an inevitable decline of the agencies of the former Kingdom of Two Sicilies, now merely the southern half of a single greater nation. This decline took its toll on theNunziatella, which became, and has remained ever since, not the one academy responsible for turning out officers for the Kingdom—later, Republic—of Italy, but, rather, a respected military preparatory school.

In 1908,

amid all the tradition, the Nunziatella took the innovative step

of permitting, even encouraging, young graduates to pursue careers other

than military. The school thus established itself—and today, still

sees itself—as a well-spring of values important in all walks

of life. The most famous student ever to attend La Nunziatella was,

no doubt, King Victor Emmanuel III. It is, however, the lesser known

graduates —the doctors, lawyers and, of course, officers—who

remain the great source of pride for the Nunziatella.

Solfatara, Totò (2)

One of my favorite Totò films

is "47, Morto che parla" (47, Dead Man Talking). The title has to do

with the smorfia, the tradition of interpreting

dreams, of associating numbers with certain things in dreams and then

playing those numbers in the lottery. The presumption is that someone

on "the other side" is giving you a hot tip. Number 47 in the Smorfia

is Dead Man Talking, so if you have a dream in which you are conversing

with, say, one of your dearly departed, 47 is one number you should

play. Unfortunately, you need at least three "hits" to have any chance

of making real money. That's three friends in very high places—perhaps

too much to ask in any one week.

The film was made in 1950 and is a loose adaptation of a stage comedy of the same name by Roman playwright, Ettore Petrolini (1886-1936) with some of Moliere's The Miser thrown in. The whole plot revolves around getting a skinflint Baron, played by Totò, to reveal where he keeps a large stash of money. The conspirators figure that the best way to do this is to make Totò believe he is dead, have him wake up in the afterlife, and then get him to talk about what he did in life and where he hid things such as money. They drug him and cart him away to a Stygian landscape replete with fumaroles and other Dantean special effects; when he comes to his senses, those who were his friends in life are standing around in bed sheets and laurel wreaths, moaning and otherwise impersonating characters whom you might expect to meet in the doom and gloom antechamber of the hereafter.

I won't spoil the rest of the film for you, but I remember being taken with the set for the scene where he wakes up: barren hillside, lots of rocks, smoke and steam. It turns out that it was filmed on location in Naples— right outside of Naples, really, in the Solfatara, a very active and bubbling sulphur pit. It is located in the area known as the Campi Flegrei. Indeed, Petronius, in The Satyricon reminds us…

| Est

locus exciso penitus demersus hiatu Parthenopen inter magnaeque Dicarchidos arva, Cocyti perfusus aqua… (Satyr., CXX, 67-9) …that between Neapolis and the vast fields of Dicearchia [modern–day Pozzuoli] there is a place at the bottom of a cavern washed by the waters of the Cocytus*... [*One of the four mythological rivers of the netherworld, on the shores of which wandered the souls of those who had known no proper burial at death.] |

Strabo (66 B.C. -24 A.D.) also mentions the Solfatara in his Strabonis geographica, calling it Forum Vulcani, the abode of the god, Vulcan, and the entrance to Hades.

The

Solfatara is, at present, a protected nature reserve open to tourism.

It is, indeed, at the "bottom of a cavern"—a large crater of volcanic

origin and one that is still very active, geologically. In its long

history, the Solfatara has suffered from benign neglect as well as commercial

exploitation, having been mined for is alum and chalk as well as serving

as a source for mineral water with reputed medicinal value. Its value

as a scientific station for the study of the geologically very interesting

activity in the area started in 1861 when the property was purchased

by the De Luca family, which included Francesco De Luca, a physicist.

His scientific descriptions of the area, the mineral content of the

soil and waters, etc. are still informative reading. The area was officially

opened to visitors in 1900 but had long been—bound as it is to

Greek and Roman Mythology—a stop on the so-called "Grand

Tour".

The

Solfatara is, at present, a protected nature reserve open to tourism.

It is, indeed, at the "bottom of a cavern"—a large crater of volcanic

origin and one that is still very active, geologically. In its long

history, the Solfatara has suffered from benign neglect as well as commercial

exploitation, having been mined for is alum and chalk as well as serving

as a source for mineral water with reputed medicinal value. Its value

as a scientific station for the study of the geologically very interesting

activity in the area started in 1861 when the property was purchased

by the De Luca family, which included Francesco De Luca, a physicist.

His scientific descriptions of the area, the mineral content of the

soil and waters, etc. are still informative reading. The area was officially

opened to visitors in 1900 but had long been—bound as it is to

Greek and Roman Mythology—a stop on the so-called "Grand

Tour".

There have

been a number of recent documentaries on Italian national TV about the

Solfatara. They refer to the site as an "active volcano" and have used

it—with nearby Vesuvius, of course—as a point of departure

to discuss the geology of the entire Bay of

Naples.

NapoliMania

Five

years ago, Enrico Durazzo opened a shop called "NapoliMania". By now,

the enterprise has grown into a chain of eight shops throughout the

city, more than 30 in the entire Campania region, one in Rome and one

in Milan. They are what we might call "novelty shops"—t-shirts,

beverage mugs, coasters, pictures, and assorted gizmos and—as

Italians now say in imported English—"gadgets". (Friends are always

asking me for a precise distinction between "gizmo," "gadget,"

"thingamajig," and "whatchamacallit". Who am I, Thomas Aquinas?)

Five

years ago, Enrico Durazzo opened a shop called "NapoliMania". By now,

the enterprise has grown into a chain of eight shops throughout the

city, more than 30 in the entire Campania region, one in Rome and one

in Milan. They are what we might call "novelty shops"—t-shirts,

beverage mugs, coasters, pictures, and assorted gizmos and—as

Italians now say in imported English—"gadgets". (Friends are always

asking me for a precise distinction between "gizmo," "gadget,"

"thingamajig," and "whatchamacallit". Who am I, Thomas Aquinas?)

Everything in the shop has to do with Naples: the t-shirts are emblazoned with slogans or proverbs written in Neapolitan dialect; there are pictures of Vesuvius and models of Pulcinella, etc. There is even an "Emergency Kit" for Neapolitans when they travel; the kit includes a sealed can of Neapolitan air and a small Neapolitan coffee machine replete with instructions from the great playwright, Eduardo De Filippo, on how to prepare the only cup of coffee worth drinking. This is important, because when you get as far north as, say, Rome, Lord knows you sure can't drink that swill they make up there.

NapoliMania capitalizes on the abundance of well-known Neapolitans in show business. There is a painting that reproduces the main facade of the Royal Palace. In the 1880s the facade was adorned with eight statues depicting the first monarch of each dynasty that has ruled Naples since the 12th century, from Roger the Norman to the first king of united Italy, Victor Emmanuel II. The NapoliMania rendition has superimposed the heads of Totò, Eduardo De Filippo, Massimo Troisi, and others on the statues. The row includes Diego Maradona, an Argentine, but, for all practical purposes, as Neapolitan as they come, since it was he who led the powerhouse Naples soccer team of the 1980s.

Along that

line is, perhaps, their most popular item: Leonardo's The Last Supper

with Neapolitan celebrities at the table. At the center, in place of

Christ, is Sophia Loren. (I have not inquired of the artist --Durazzo,

himself-- why he made that particular choice, nor have I asked Sophia

how she feels about the honor.) It is more intriguing to see who is

cast in the role of Judas. Traditionally, Judas is thought to be fourth

from the left in Leonardo's painting. In the NapoliMania version, that

person is standing in back of the table, facing to his left. It is actor

Carlo Giuffrè. (Again, I haven't asked.) The others are comic

Totò, three members of the theatrical family of De Filippo (brothers

Eduardo and Peppino, as well as Eduardo's son Luca), Vittorio De Sica,

comic Massimo Troisi, contemporary singer-songwriter Pino Daniele, actor

Nino Taranto and singer Massimo Ranieri. Two of the twelve disciples

are the Neapolitan mask figure, Pulcinella, and the traditional

figure of the Neapolitan street-crier, the Pazzariello,

the character dressed in mock military garb who—until well

into the 20th century—used to parade around the streets

shouting out advertising for shops and services. Sophia Loren is the

only woman in the painting.

Bookshops, libraries (2)

The

paper reports on a poll conducted by ALL (Adult Literacy and Life Skills)

that says 73% of those interviewed in the Naples area had never been

in a library and 45% had never set foot in a book–shop. The numbers,

so says the report, are particularly grim when it comes to the 16–31

age group, those who are about to leave school or who have recently

left school. They do not seem to have picked up the reading habit in

their studies.

The

paper reports on a poll conducted by ALL (Adult Literacy and Life Skills)

that says 73% of those interviewed in the Naples area had never been

in a library and 45% had never set foot in a book–shop. The numbers,

so says the report, are particularly grim when it comes to the 16–31

age group, those who are about to leave school or who have recently

left school. They do not seem to have picked up the reading habit in

their studies.

I am not sure how to interpret numbers like that. I have lamented in another entry the fact that there is no public library system to speak of in Naples. It is simply not part of the cultural history of the area. There is an extensive system of private libraries usually going back to prominent persons in the intellectual history of Naples. That is, for example, if you want to browse in what used to be Benedetto Croce's private library, you can do that at the institute founded in his name, where all his books now reside (see number 5 on map page). That pattern is repeated throughout the city. Getting into these places is a bit iffy, at times. It's almost like a Prohibition speak-easy—the knock on the door, the peep-hole, the panel sliding back, Joe the Bouncer asking you what you want, the password and countersign (maybe something like a whispered "Fahrenheit 451," and "Equals Centigrade 233". That's close enough; you might get in). Many important collections of books have also found their way into the National Library of Naples or one of the many university libraries in the city. The National Library is open to the public, but it is somewhat like the Library of Congress in the United States—browse, read, yes, but take home, no. The university libraries are along the same lines. The nice little public library down on the corner that issues you your free pass to lifelong learning does not exist.

Bookshops are another matter. There is a street in the historic center of Naples called via San Biagio dei librai—"Saint Biagio of the book sellers". (Saint Biago was a 17th-century monk ordained in Naples. I was hoping that he might turn out to be the patron saint of booksellers. That appears not to be the case; that honor goes to, among others, John the Apostle and Thomas Aquinas, the later of whom used to teach on the "book street". Pretty stiff competition for poor Biagio. Anyway…). The street still features a great number of small bookshops, usually dealing in old or even antique books. It also runs right through the university section of Naples, and there is a corresponding spike in the bookshop curve as you get to Piazza San Domenico Maggiore. Interesting, however, is the great number of sidewalk bookstalls that probably don't fit in a pollster's definition of "book shop" but do brisk business. Also, the street that runs from Piazza Dante to Port'Alba has at least a dozen bookshops along 75 yards of street. Many of these are used books stores that advertise prominently, "We buy books".

The Barnes

and Noble syndrome—the book supershop that, besides books, also

has CDs, DVDs, many other fine acronyms, a coffee shop and places to

sit and read—has come to Naples. There are two Feltrinelli stores

in Naples. They fit the above description, especially the newer of the

two (photo) at Piazza dei Martiri. A new wrinkle in town is the recent

opening of FNAC, originally a French chain, in the Vomero section of

town. It has all of the above and, as well, a computer section and Internet

cafe. They tell me that the shop in Paris has seven floors. In Naples,

it has but two, but with the business they seem to be doing, they may

have to invade the rest of the block.

Risanamento (3); Serao, Matilde (2); urbanology (5)

The last

sentence in the entry about the Risanamento, about the urban renewal of

Naples in the late 19th- and early 20th century, is this:

| It is a sad irony that the Risanamento of Naples coincided almost exactly with the period of greatest emigration away from Naples by the very persons who, at least on paper, were to have benefited from the rejuvenation of their city. |

I certainly would have written that differently if I had thought

more about it. The fact of the matter is that the connection between

the Risanamento and massive emigration was not a coincidence—it

was cause and effect.

I certainly would have written that differently if I had thought

more about it. The fact of the matter is that the connection between

the Risanamento and massive emigration was not a coincidence—it

was cause and effect. Somewhere in the back of my head, I think I knew that large numbers of people had had to pick up and move when the project to rebuild Naples started in the 1880s. Then I heard someone mention the other day that "half the population of the city was displaced". That comes out to hundreds of thousands of people. They either moved to state-built shanty towns hastily cobbled together for the duration of the project (30 years), or they moved in with relatives or friends outside the affected area—or they left Italy. Thus, the Risanamento was largely responsible for massive emigration to the New World; they didn't just happen to coincide.

I was again made aware of the enormity of the project the other day by looking at a map of the area of Santa Lucia before the Risanamento and one of the same area after it had been rebuilt. The project changed the entire coastline of the city from Mergellina to the main harbor—well over a mile. The beautiful new sea-side road, via Caracciolo, from Mergellina to the center of town was, perhaps, necessary, and it looks fine today. Yet when they extended that road along the coast to make it the new road into town and lined it with high hotels, they (1) hid from view the original height of Pizzofalcone, the cliff across from Castel dell'Ovo (the hotels are higher than the cliff), and (2) relegated the historical sea-side road, via Santa Lucia, to the role of a secondary road running behind the hotels. That part of the Risanamento, alone, involved the construction of 15-20 blocks of buildings built on landfill in the original waters of Santa Lucia.

When Agostino Depretis (1813-87) was the head of the Italian government in the early 1880s, he used the phrase, "Bisgona sventrare Napoli"—Naples must be gutted. It was a bad choice of words. Another translation might prefer "disembowelled," but, either way, it's a violent metaphor. That is the phrase that stuck in the craw of those who were, if not totally against the Risanamento, at least very circumspect in their approach to solving the problems of overcrowding and disease, both of which were undeniable facts of life in the Naples of the 1880s. On the other hand, these critics weren't too happy with the state-coined euphemism, Risanamento, either—which means, literally, "Making Healthy Again".

The project, for better or worse, went ahead. Matilde Serao used Depretis' infelicitous phrase in the title of her book, Il ventre di Napoli (The Bowels of Naples). The book first appeared in serial form in nine installments in a newspaper in Rome, where Serao was living in 1884. In August and September of that year, Naples suffered its fifth and worst cholera epidemic in the 25 years since its incorporation into united Italy. The death toll was 7,000, and Prime Minister Depretis was convinced that the overcrowded and filthy center of Naples simply had to be torn down, aired out, and cleaned up (with a modern sewage system, among other things). The first chapter of Serao's book is in the form of a letter to Depretis, taking him to task for not really understanding Naples and its problems. Did he really think that building a few new streets was going to fix the problems of a city where poverty is so endemic that an entire family lives in one room—where they are born, where they eat, sleep, and die in a single room? In 1904, 20 years after the project started, and at a time when much of the Risanamento had either been completed or was in various stages of completion, Serao damned it with faint praise—the new university building is nice, she said.

[Also

see here.]

Gravina (palazzo)

One of the most impressive examples of Renaissance architecture

in Naples is the Palazzo Orsini di Gravina, located 100 yards north

of the main post-office and directly across the street from the statue

of the last Hapsburg King of Spain, Charles II (known as "Il Reuccio"

—the Little King). The original building was

erected between 1513 and 1549 by Gabriele d’Angelo along lines

dictated by the Florentine Renaissance. It was commissioned by and named

for Ferdinando Orsini, Duke of Gravina. Much of the external decorative

masonry was destroyed in a fire in 1848. Restoration, however, respected

the original Renaissance ideas of the designer. There are niches in

the facade, each containing a bust of a member of the Orsini family.

They are 19th century copies of the original 16th century works of Vittore

Ghiberti. Since 1936 Palazzo Gravina has housed the Architecture Department

of the University of Naples (see here).

Bourbons (7), (coat of arms)

Heraldry is the study of coats of arms. The "herald" was a medieval court officer responsible for maintaining records of coats of arms and titles of nobility. The emblems on a coat of arms were the individual's own distinctive marks; thus, the arms were the property of a person rather than of a government. Although coats of arms were originally used in battle for recognition of those otherwise unrecognizable (encased as they were in complete suits of armor), once introduced, the coats of arms were retained, even when displayed elsewhere. The widespread emergence of heraldry in the Middle Ages is associated with the Crusades and chivalric tournaments, which provided the opportunity for knights from all of Latin Christendom to come together as well as meeting the need to identify these knights on the battlefield and in tournaments.

The emblems used to mark an individual were various and might include animals, crosses, plants, letters, castles, and obscure symbols. Such emblems might be the individual's own emblem, one acquired through marriage, or an ancestral one; the emblems could show alliances or claims to fiefs and property rights; they often symbolized various honors bestowed upon the bearer or the bearer's ancestors and indicated various orders of which the bearer was a member; and, in some cases, the symbols represented historical events connected to the bearer's family history.

Although individual, the coats of arms, displayed on an appropriate flag, often came to symbolize the state, itself, as is the case with the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Naples, also known as The Kingdom of Two Sicilies. The Neapolitan branch of the House of Bourbon was the last dynasty to rule Naples before its incorporation into a united Italy. The Bourbons ruled from from 1735 to 1860, except during the Napoleonic interlude. The coat of arms of the Kingdom of Naples displays various historical connections between the Neapolitan Bourbons and other European nobility.

For purposes of this description and with intense apologies to

specialists, I shall dispense with the obscure vocabulary of heraldry.

Looking at the coat of arms, you see that the shield is divided, vertically,

into thirds. In the left third are the arms of Farnese consisting of

blue fleurs de lis on gold. This three-pointed stylized flower,

based on the lily was the symbol of the French Bourbon dynasty.

For purposes of this description and with intense apologies to

specialists, I shall dispense with the obscure vocabulary of heraldry.

Looking at the coat of arms, you see that the shield is divided, vertically,

into thirds. In the left third are the arms of Farnese consisting of

blue fleurs de lis on gold. This three-pointed stylized flower,

based on the lily was the symbol of the French Bourbon dynasty.

In the same third of the shield, Austrian connections are shown by the red-white-red horizontal stripes (still the flag of modern Austria, by the way); close-by are the blue and gold diagonal stripes of ancient Burgundy. In the middle of that third of the shield and imposed over the rest of the emblems are the arms of Portugal.

The center third of the shield is particularly complex. At the top, the "quartered" display on the left shows two segments with castles representing the Spanish house of Castile; the other two segments show lions for the House of Leon. At the bottom of that segment of the quarter, the small triangular section with a flower represents Granada. To the right of that quartered section are the four red poles on gold representing the House of Aragon; to the right is another "quarter" showing, again, two segments of Aragon and two of Sicily (a crowned black eagle).

In the middle of the center third of the shield, most prominent, are the arms of the House of Bourbon—three golden fleur de lis set on blue with a red border. These arms are imposed over the Austrian red-white-red on the left and the golden fleur de lis on blue with a red border of modern Burgundy.

The lower part of the center third is "quartered" and shows in the upper-left quarter the diagonal stripes of ancient Burgundy with the black lion on gold of Flanders; in the upper- right quarter are the golden lion on black of Brabant and the red eagle on silver of Tyrol; the lower-left quarter represents the Sicilian House of Anjou with golden fleurs de lis topped by a red lambel; the lower-right quarter shows the golden cross on silver of Jerusalem flanked by four other small crosses.

The right third of the shield is the simplest. It shows the arms of Medici: a gold field with five red balls and a blue upper bigger ball on which are displayed three golden fleurs de lis.

There are six orders displayed, hanging from the collars at the bottom of the coat of arms. From left to right they are:

·

the military order of King Francis I;

· the order of St. Ferdinand and of Merit;

· the order of St. Januarius (top center);

· the order of the Golden Fleece (center bottom—this

is among the oldest chivalric orders in Europe and was founded by Philip

III, Duke of Burgundy, at Bruges in Flanders in 1430, to commemorate

his wedding to Isabella of Portugal);

· the Constantinian Order of St. George;

· the Spanish Order of Charles III.

At the very top of the coat of arms, of course, is the royal crown. The crown is topped by a cross, representing the intense Catholic nature of the kingdom.

As might be expected of a coat of arms representing a dynasty founded by a Spanish prince (Charles III) of an originally French dynasty (Bourbon), this one is very Spanish and very French: heraldic symbols from Spain abound, and the Bourbon arms are at the center of everything. In terms of general design, its complexity is Spanish. The coat of arms has, however, a simpler side to it: it does not display "supporters" on the side—that is, human or animal figures on one or both sides of the shield, supporting it—nor does it display a helmet with or without a crest at the top, choosing, instead, to show the crown mounted directly on the shield. This simpler display was typical of French heraldry starting in the 18th century.

There is, indeed, a modern Bourbon pretender to the throne of Naples—Prince Ferdinand, Duke of Castro. He resides in France with his wife, the Duchess of Castro, the former Countess Chantal Frances de Chevron-Villette. There is even a Neo-Bourbon Society in Naples, which exists—according to their literature—not to restore the Kingdom of Naples, but to get southern Italians to appreciate their history. In 1999 they held a small demonstration in the historic center of the city to commemorate the Bourbon counter-revolution that defeated the Neapolitan Republic in 1799. More recently—and mundanely—they even held a Miss Kingdom of Two Sicilies beauty pageant!

Ironically, the modern Bourbons seem to get along quite amicably with the modern Savoys, the dynasty that defeated them in 1860 and that ruled Italy until deposed by popular referendum in 1946. The two houses give each other honors; the Duke of Castro has received the Order of the Annunciation of the House of Savoy, and the Duke of Savoy has received the Constantinian Order of Saint George of the House of Bourbon of Naples, as did his late father, King Humbert II. This friendliness should not be surprising in spite of the enmity between the two houses caused by the unification of Italy. Prior to that time, there were numerous episodes of intermarriage between the Bourbons of Naples and the Savoys, the most prominent of which was in 1832 when Ferdinand II of Naples married Cristina, daughter of Victor Emmanuel I, the Savoy monarch of Sardinia.

Also, see

the entries about Naples under the Bourbons: (1)

, (2) and (3)

as well as other the items "Bourbons" in the subject

index .

Ferdinando e Carolina (film)

Among

light-hearted films about Naples, two of my favorites are still Vittorio

de Sica's La Baia di Napoli (1960) (English title: It Started

in Naples) with Clark Gable and Sophia Loren, and Billy Wilder's 1972

film with Jack Lemmon and Juliet Mills entitled Avanti. That

Italian word was the title in the original English-language release

of the film. It means, "forward," "go ahead," and "come in" and ran

through the film every time somebody knocked on a door, which was quite

often. One of the most amusing things about that delightful film was

that when it was released in Italy, they had to invent another Italian

title since Avanti also happens to be the name of the newspaper

of the Communist party of Italy. The revised Italian title came out

as the god-awful "What Happened Between My Father and your Mother".

Even a party slogan at every door-knock is better than that title.

Among

light-hearted films about Naples, two of my favorites are still Vittorio

de Sica's La Baia di Napoli (1960) (English title: It Started

in Naples) with Clark Gable and Sophia Loren, and Billy Wilder's 1972

film with Jack Lemmon and Juliet Mills entitled Avanti. That

Italian word was the title in the original English-language release

of the film. It means, "forward," "go ahead," and "come in" and ran

through the film every time somebody knocked on a door, which was quite

often. One of the most amusing things about that delightful film was

that when it was released in Italy, they had to invent another Italian

title since Avanti also happens to be the name of the newspaper

of the Communist party of Italy. The revised Italian title came out

as the god-awful "What Happened Between My Father and your Mother".

Even a party slogan at every door-knock is better than that title.

Last night I saw an interesting addition to the genre of light-hearted films about Naples: Ferdinando e Carolina, directed by Lina Wertmueller and released in 1999. It is, in Wertmueller's words, a "libertine comedy" about a very unfunny period in the history of the Kingdom of Naples, the period before the French Revolution when the young, oafish, and virile Ferdinand IV was running around the woods hunting while his very able wife, Caroline of Hapsburg, was making plans to run the kingdom. (See The Bourbons, Part 1.)

The story is told in a series of flashbacks running through the mind of Ferdinand on his death bed in 1825, after Napoleon had come and gone and after Carolina had died. He is tormented by the ghosts of his violent past, the liberals and Neapolitan revolutionaries he had had executed. In short, we see his youth, from fun-loving pseudo-urchin to fun-loving and vulgar young stud. It was enjoyable to watch. Like everything that Wertmueller does, Ferdinando e Carolina has that bit of Fellini and Zeffirelli about it, such that if you freeze almost any frame in the 102–minute running time, you have a frameable portrait, so perfect are the sets, costumes and choreography. Wertmueller points out that the shots of the inside of what was supposed to be the Bourbon Royal Palace were actually shot in the Savoy palace in Turin—a bit of "revenge" she says.

The film

featured Sergio Assisi as Ferdinando and Gabriella Pession as Carolina.

Assisi is a still relatively little-known actor. After the film was

released, he appeared at a book-signing in Naples with Giuseppe Campolieti,

the author of Il Re Lazzarone (roughly, the Beggar King), a recent

biography of Ferdinand. Assisi read passages from the book in Neapolitan

dialect. That was one of the charms of the film, too—much of it

was in the language of Naples, the only

language that the king ever really felt comfortable speaking. I don't

know anything about Gabriella Pession except that she either spoke—or

was dubbed (more likely)—with a thick German accent, all in keeping

with Queen Caroline's Austrian origins.

It's not really a fjord, though that is what they call it,

but, as a tree-hugging ecophile, I am happy to see that they are attempting

to restore this remarkable bit of terrain on the Amalfi coast.

It's not really a fjord, though that is what they call it,

but, as a tree-hugging ecophile, I am happy to see that they are attempting

to restore this remarkable bit of terrain on the Amalfi coast.

The

Villa Comunale houses the Anton Dohrn Aquarium (top photo). In

1870 Anton Dohrn (1840-1909), German zoologist and disciple of Darwin,

requested and got permission to build a “Zoological Station”

—an aquarium— in Naples. He was given a site within the

Villa Comunale and the project was begun in 1872 under Oscar Capocci

and finished by the German architect Adolf von Hildebrand. Interesting

artwork within the Florentine Renaissance building include murals by

the German artist Hans von Mareès, who drew inspiration from

characteristic fishing scenes of the Mediterranean, especially Naples

and Sorrento. Since its inception, the aquarium in Naples has not only

served as an exhibition of marine flora and fauna, but has also been

a working research facility in marine biology.

The

Villa Comunale houses the Anton Dohrn Aquarium (top photo). In

1870 Anton Dohrn (1840-1909), German zoologist and disciple of Darwin,

requested and got permission to build a “Zoological Station”

—an aquarium— in Naples. He was given a site within the

Villa Comunale and the project was begun in 1872 under Oscar Capocci

and finished by the German architect Adolf von Hildebrand. Interesting

artwork within the Florentine Renaissance building include murals by

the German artist Hans von Mareès, who drew inspiration from

characteristic fishing scenes of the Mediterranean, especially Naples

and Sorrento. Since its inception, the aquarium in Naples has not only

served as an exhibition of marine flora and fauna, but has also been

a working research facility in marine biology.  Even a cultural oaf such as myself is overwhelmed by the Amalfi

cathedral: The beautiful façade portraying Christ between the

symbols of the Evangelists, which, fittingly, gleams so brightly in

the noonday sun that you have to avert you eyes; the thousand-year-old

bronze doors from Constantinople; the Arab–inspired multihued

majolica tiles of the dome; an altar designed by the great Domenico

Fontana; the crypt containing the remains of St. Andrew (to whom the

cathedral is dedicated)—all of it is stunning. (Also see

Even a cultural oaf such as myself is overwhelmed by the Amalfi

cathedral: The beautiful façade portraying Christ between the

symbols of the Evangelists, which, fittingly, gleams so brightly in

the noonday sun that you have to avert you eyes; the thousand-year-old

bronze doors from Constantinople; the Arab–inspired multihued

majolica tiles of the dome; an altar designed by the great Domenico

Fontana; the crypt containing the remains of St. Andrew (to whom the

cathedral is dedicated)—all of it is stunning. (Also see